A Quick Trip to Ireland

A few weeks ago I was asked to show an ICAA tour around a house in Ireland called Kilboy, which my father and I designed some years ago. I caught a late flight to Ireland on a Sunday night. I then had to hire a car and drove for over an hour in the peaty darkness using my phone as a satnav praying that the battery would hold out. Eventually, I arrived at Roundwood House, a charming hotel somewhere in the blackness - having relied on satellite I had no real idea where I was. Tired and ready for bed, I walked up the mossy steps, entering this most Irish of houses. In the semi-darkness, I could be forgiven for not recognising William Laffan, the architecture historian and art dealer standing in the hall. His eyes must have been better adjusted as he greeted me warmly and within minutes we were sitting in one of the drawing rooms drinking obscure whiskeys with Paddy, the owner of the house. In moments, I had forgotten how tired I was and enjoyed chatting by a fire with two virtual strangers who had quickly become the greatest of friends.

Some hours later I staggered to bed. When I awoke the intense green of my room became evident. When I say green, I don’t mean some tasteful grey/green from a Farrow and Ball paint chart, I mean proper green, like the green from Babar the King of the Elephants’ suit. The Irish have a taste for these extreme colours. A fashion started perhaps by Mariga Guinness who famously painted the Knight of Glin’s drawing room a dark inky blue. These colours appear so confident and unselfconscious, nowadays highly paid interior decorators presumably earn a fortune specifying this rather outré palette but I imagine (and hope) that this particular green was chosen during a hurried trip to a nearby hardware store and this was the only shade they had.

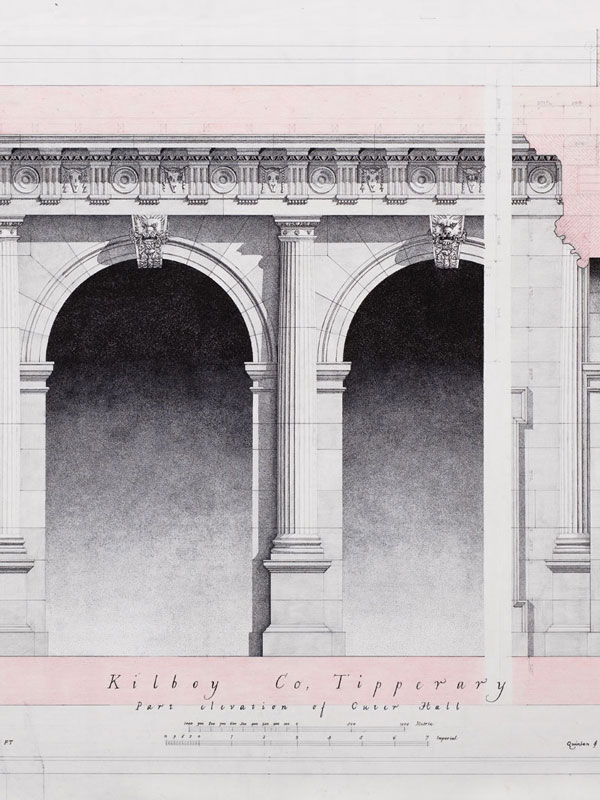

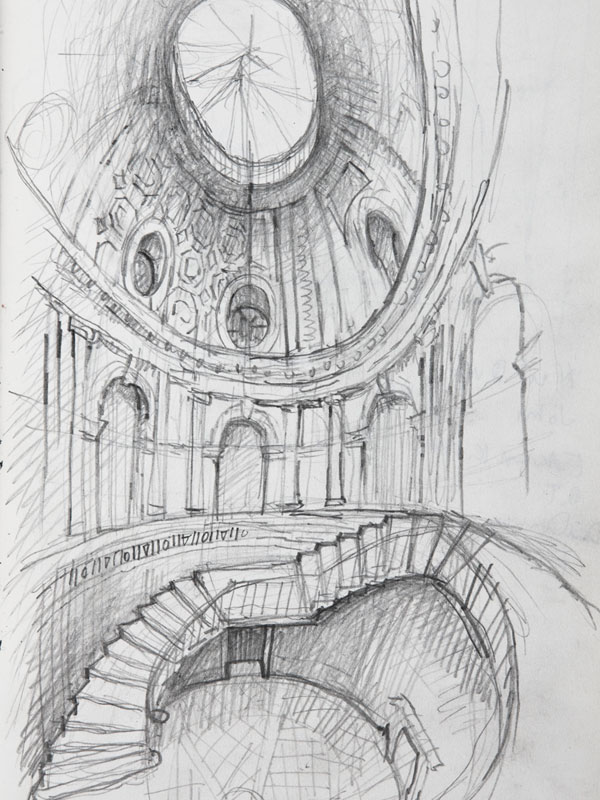

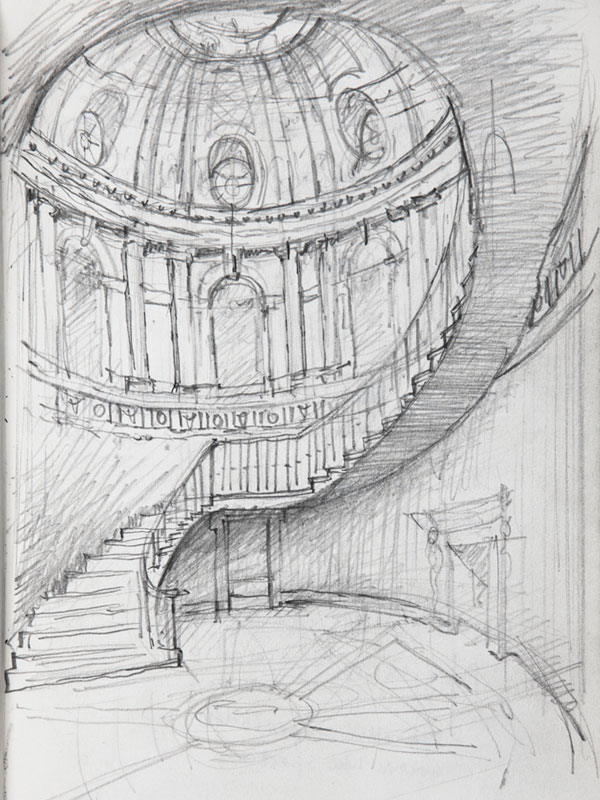

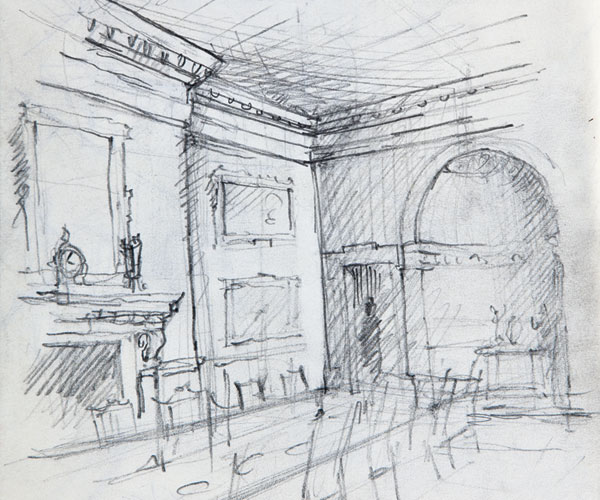

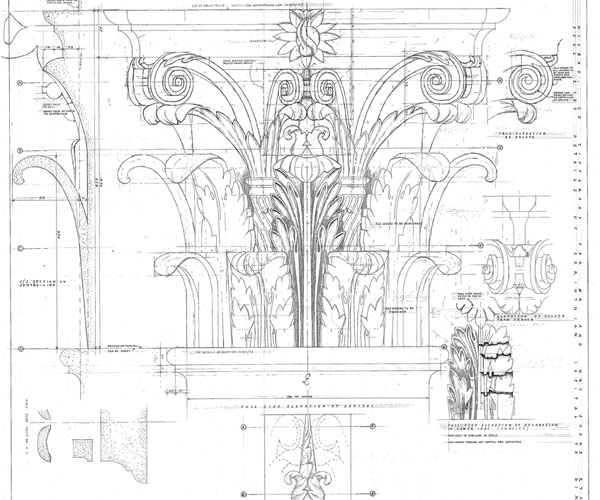

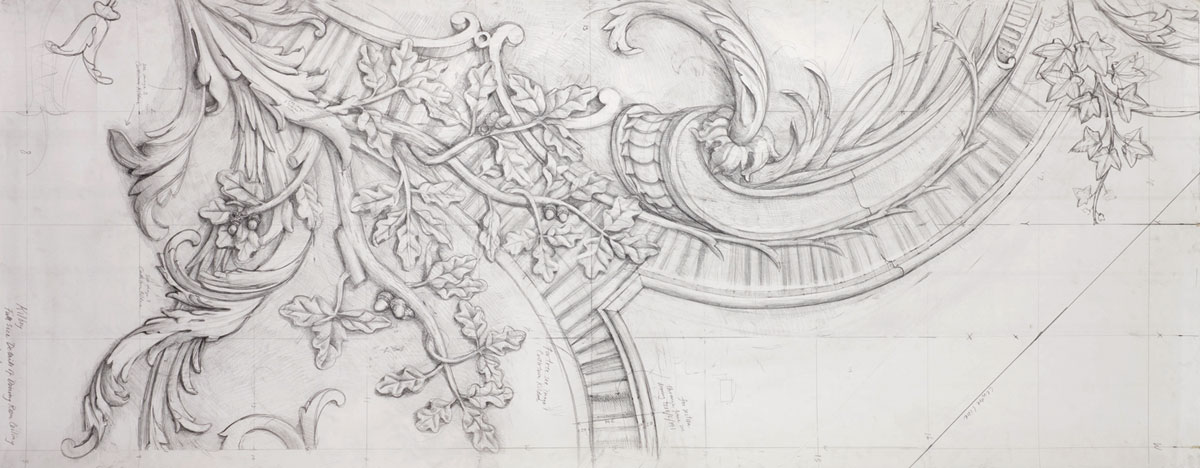

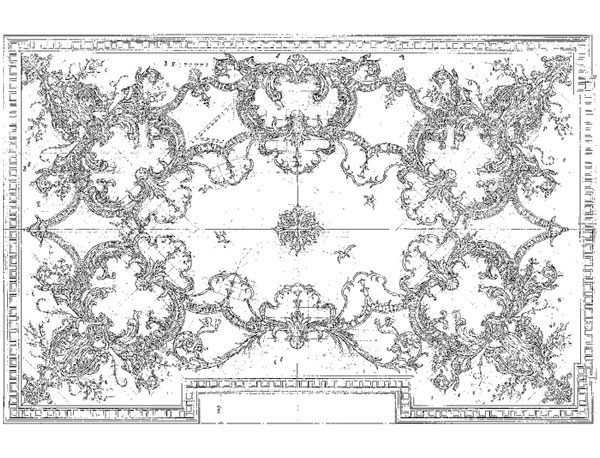

The next day I went to Kilboy in a coach, with the touring party. The house was looking amazing and it was a real pleasure to return. Something that particularly pleased me was the Irish look of the house, this was an important aspect of the design process and now a few years on, it is happily settling into its context. Country Life generously described it as ‘the greatest new house in Europe’ and seeing it again made me remember what a special project it was. I enjoyed describing the project to the group and who kept saying, ‘it’s amazing!’, to which I replied ‘I know!’. This may at first sound conceited but I am acutely aware that it was not just my father and me who made this project what it was. Hundreds of craftsman and professionals worked to achieve the vision of an exceptional client - it was a rare combination of events.

In the afternoon we went to Birr Castle, a huge gothic pile which has been there since the 12th century but much altered in the Victorian era. We were shown around by the Earl of Rosse himself who was absolutely delightful. Much of the castle’s fame comes from various scientists in the family, one of whom accurately worked out the temperature on the surface of the moon, back in the 19th century - a curious concern but his calculations proved to be correct when the moon was visited many years later. A neglected grey stone structure, to house his massive telescope, sits like a ruined gothic chapel gathering moss in the grounds not far from the castle.

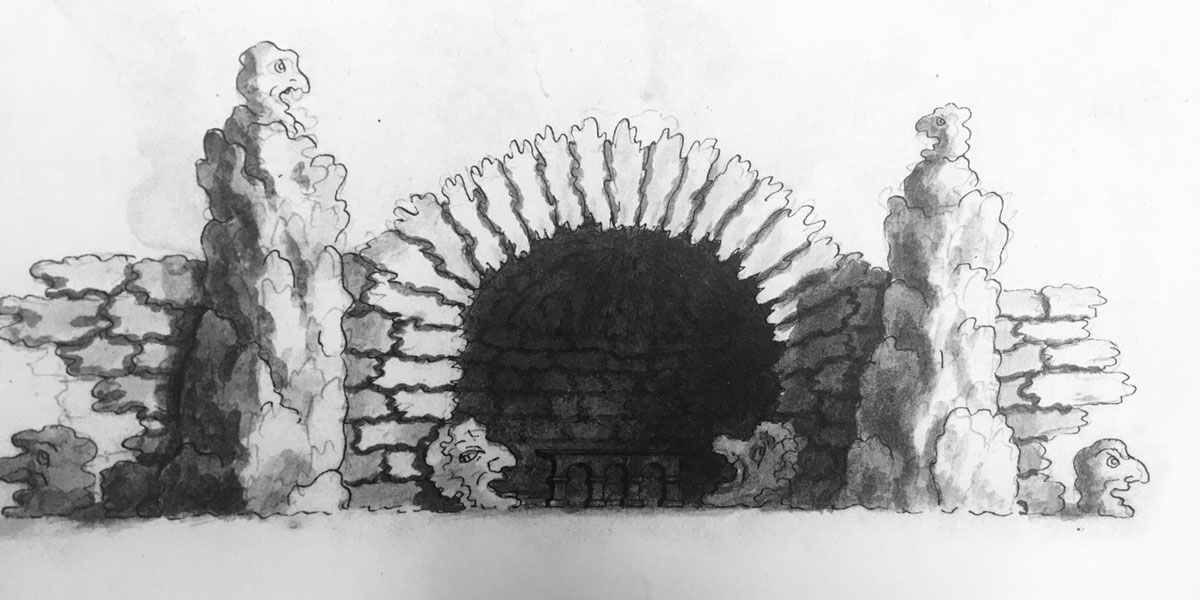

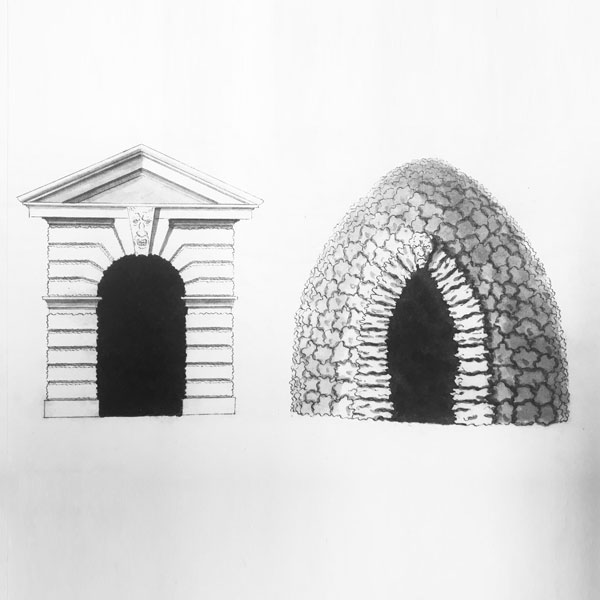

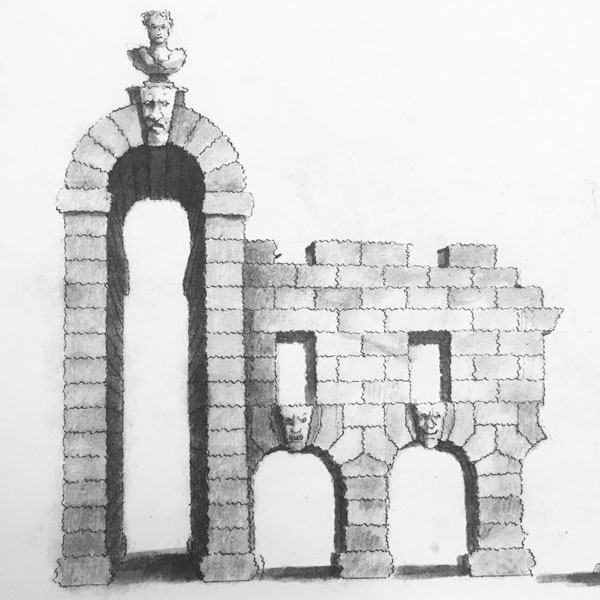

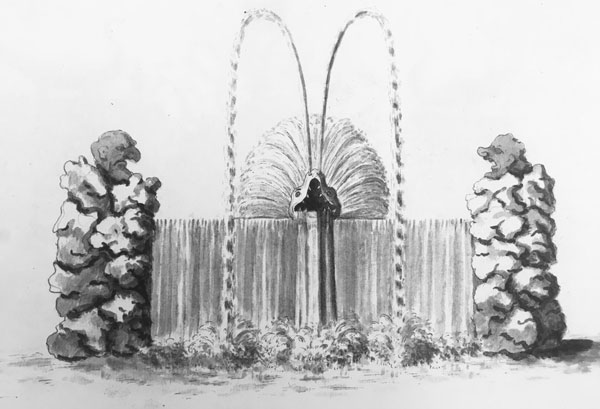

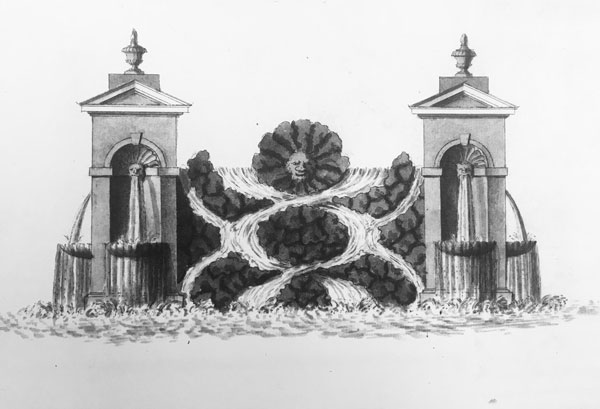

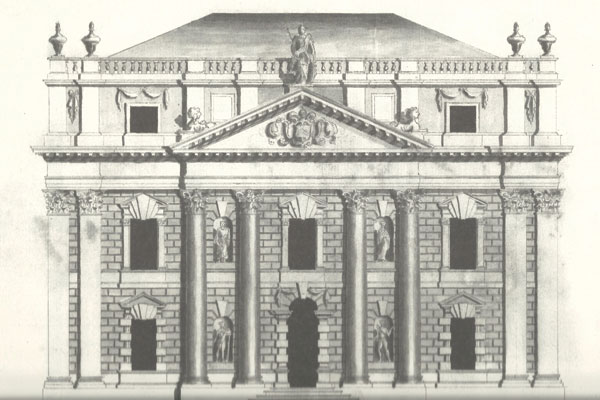

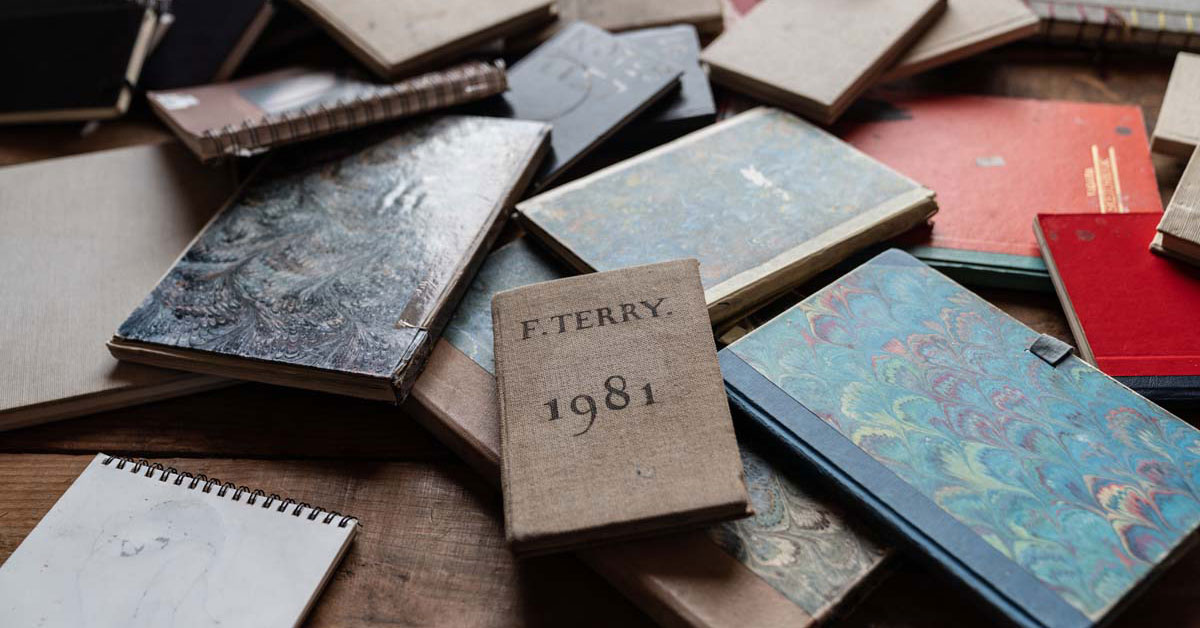

After the tour, we had a glass of sherry in the hall and then on to lunch in their exquisite, red damask, Victorian Gothic dining room. The whole occasion seemed so ‘old money’ that I had low hopes for the taste of the food. But I was pleasantly surprised by the delicious venison, complete with wild cress from the moat, which they insisted should be eaten by hand served from a kylix shaped crystal bowl with a silver stand. After lunch in their drawing room, over a cup of coffee, I leafed through the original copy of Miscelanea Structura Curiosa which is a folio of drawings by Samuel Chearnley, a gentleman architect from the 18th century who unfortunately died at the age of twenty-nine. As the title suggests, these are drawings of curious fantasy buildings like fountains, obelisks and grottos all rendered in pen and wash with a careful amateur hand and a surrealist imagination. This collection has been recently reproduced as a book and was edited by William Laffan, who I had been drinking with the night before.

That evening we had supper at Ballyfin one of the last great houses of Ireland which had been beautifully restored and furnished. In fact, it took longer to restore than originally build, which is a measure of the quality. It now is a luxury country house hotel, perhaps the best in Ireland, if not the whole of Europe. The dinner was excellent and it was great to catch up with my American classical architect friends.

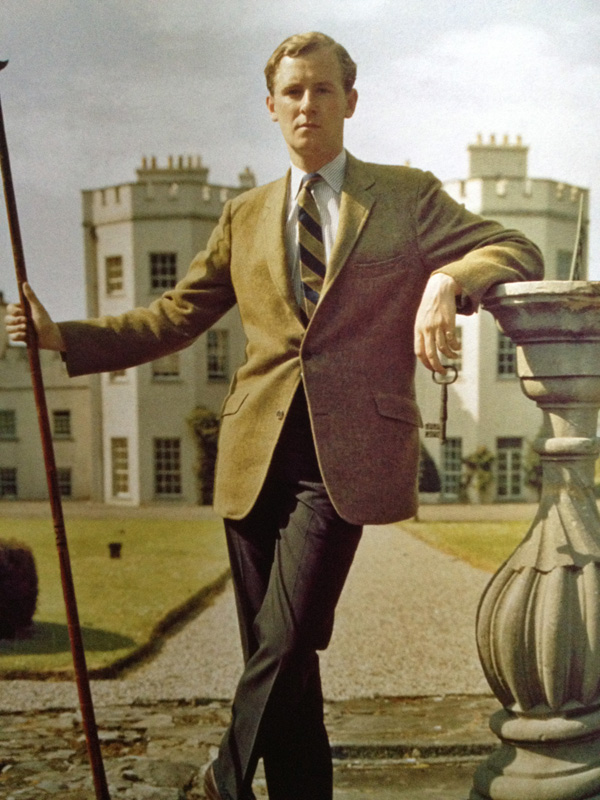

The great houses of Ireland are a treasure trove for any classical architect and when designing Kilboy I studied them in great detail. Over the course of the project, we visited some of the best, including Castletown, Carton, Russborough, Newbridge, Lyons and Townley as well as many of the great townhouses of Dublin. It is amazing, but not wholly surprising, that the Irish Georgian Society ceased to exist for many years and needed to be revived by Desmond Guinness. Perhaps, more importantly, he invited Jackie Kennedy, Mick Jagger and many other ‘60s legends to enjoy these houses which gave the whole endeavour a glamour which rarely accompanies Georgian architecture. Guinness with his then-wife, Mariga and their friend the Knight of Glin, worked tirelessly to promote this aspect of Irish heritage. These buildings cannot look after themselves, particularly with the Irish climate and so they needed energetic defenders to keep them from being lost.

The shadow of these people weighed heavily on us when we were designing Kilboy. It was not uncommon for us to ask ourselves in design meetings, ‘...what would someone like the Knight of Glin say if he saw this?’. We were keen that every detail would meet the approval of him or someone of his hallowed set. I did finally meet him at Kilboy as the project was nearing completion. I felt like Marlow finally finding Kurtz, way down the River Congo in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. But the meeting was a much happier occasion, the Knight of Glin was nothing but charm and he was generous in his praise of the house. He sadly died a few months later, but he has, in a sense, lived on through the preservation and continuance of the Irish country house tradition which is now alive and well for future generations to enjoy.