Can Beautiful Homes Be Built in a Factory?

As lockdown is slowly being relaxed, more building sites are looking to return to productivity. This is obviously problematic – from the restrictions of welfare facilities on sites to many trades trying to work around each other. Is there a safer, easier to police way of building houses that would enable social distancing to be maintained whilst still being productive and efficient?

As well as the Covid 19 crisis, housing is still a pressing issue and all the major political parties are keen to show how this problem may be solved. The government has set a target of building 300,000 homes a year by the middle of the next decade. Despite recent increases in activity, the volume of houses built is nowhere near this figure and the problem will only get worse. Policy makers are desperately trying to think of a new way to deliver more houses because the traditional methods of building are not delivering the volume required. Many people think that off-site methods are the only way of solving this problem. The perception is that it would be cheaper and quicker because it would avoid many of the problems of a traditional building site. Minimizing time on site has the following advantages:

- Building sites must deal with unpredictable weather, including rain, wind, frost or even snow which slows and sometimes halts production. Working in a factory, the temperature can be controlled and working inside also eliminates the problem of rain, snow and wind.

- Building sites are inherently dangerous.

- Less time on site means less disruption caused by noise, dust and extra local traffic.

- With skill shortages being a real problem on building sites, working off-site in a factory would help because the workers would not need to spend time travelling to different places and they could work in comfort. This would help to retain workers in the construction industry.

- Quality control is easier to monitor in a factory rather than on a building site.

All these factors work together to make the houses cheaper and quicker to build. nHouse claims it can build a house in 20 days in the factory which can then be erected on site in a matter of hours.

We are not in a hypothetical realm here, building houses in factories is already done in vast quantities. Predictably Japan and Germany are leading the way, but the U.K. has already started to embrace this new trend.

Robert Booth writing in the Guardian (31/12/17) observed the following:

“One of Britain’s major housebuilders is to prefabricate up to a quarter of its homes in a factory, in the latest attempt by the construction industry to tackle the housing shortage.

Berkeley Homes, which builds 4,000 homes a year, is planning to create a facility in Kent next year where builders will work to produce up to 1,000 houses and apartments annually which will then be craned on to sites.

Another company, nHouse, is setting up a factory in Peterborough with the capacity to build 400 homes a year, complete with light fittings, bathrooms, bookshelves and kitchens. Production is expected to start in January.”

Other developers, including Legal and General and Urban Splash, have launched prefab home divisions.

Traditionalists (like me) should not fear this development because prefabrication has been with us since classical times. There is substantial evidence that the Romans had standard column sizes which were used extensively throughout the empire. But a more critical question to ask is, can these prefabricated houses be beautiful? Beautiful boats, cars, bicycles, furniture, clothes, shoes, or whatever you care to mention, can be made in factories, and so why not houses? It can certainly be done in timber, the Americans have been building attractive prefabricated timber houses for years. To do this using heavy materials like brick is more complex but I believe quite possible. I have seen vast brick and stone wall panels for office buildings being made offsite and so I cannot see why this could not be done for housing.

In order to build in volume, houses must be popular and tap into what most people find beautiful. The modernist style can be very beautiful, but it is not for everyone. Modern style buildings generally fall into the ‘marmite’ category, you either love them or you hate them. A popular house needs to be more general in its appeal. For this I would suggest that designing in the traditional style rather than a modern style is the answer. Every estate agent knows that it is far easier to sell a traditional style house than a modern one, Georgian properties being the most popular. This is backed up by the findings of a MORI poll of 2015 which demonstrates that people prefer traditional style houses to modern by a substantial margin. The traditional style houses for this survey were taken from Poundbury and are new build classical Georgian style properties.

The popularity of the Georgian style should come as no surprise. The Georgians took beauty seriously dedicating whole architectural treatises to the study of proportion and the recording of beautiful mouldings from ancient Greece and Rome. Modernism, by contrast came from a functionalist origin with the belief that beauty would result as a consequence of building well and fulfilling the brief. But as Robert Venturi and others have observed, the Vitruvian triad of commodity, firmness, and delight, (or in layman’s terms; function, structure and beauty) is not an equation. Function plus structure does not always equal beauty, each of the three needs to be considered separately and with equal seriousness. The simple Georgian terrace or house has embodied proportional theories which go back to Palladio and ultimately ancient Greece and Rome. This is why they are generally perceived to be beautiful and the reason why they are so popular.

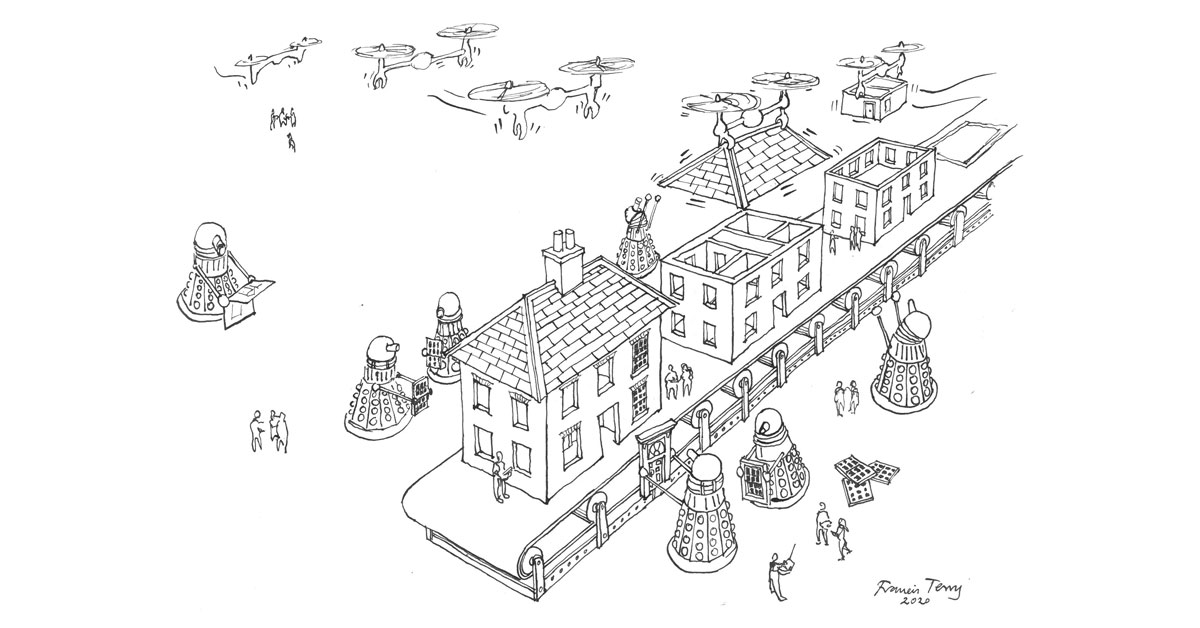

The Georgian style and specifically classicism is particularly applicable to the current housing crisis because it was built in such a huge volume and at an incredible speed. Classicism was maintained throughout the Victorian era and up until the First World War. The developers of the 18th and 19th century wanted to build quickly and cheaply and so it is useful to see how they produced beautiful buildings within the same parameters. A striking feature of these buildings is the repetition of all architectural elements. This is as much true for Downing Street as a modest Georgian terrace anywhere in the country. The use of repeated elements makes the building process more efficient because it eliminates one-off items which are time consuming and costly to produce. There is a worry that even if beautiful Georgian style buildings could be made in a factory this would not be desirable as they would all be the same and none of the houses would have any individuality. I do not see this as a problem. I have recently designed a housing range for Halsbury Homes and we deliberately made all the houses look similar and I feel that the repetition gives the buildings better group value.

This is where many new housing developments do wrong, at great expense developers make all the houses look different and the result is a very ‘noisy’ visual experience. The use of repetition has a calming effect on the eye because it does not need to process so much information. Georgian buildings are full of standard products made off-site, these include sash windows, doors, staircases, fireplaces, ceiling rosettes, cornicing and skirtings. This means that reproducing Georgian architecture is well suited to off-site factory production and the Georgian builder would have happily prefabricated whole houses if it was possible at the time.

The Classical style which the Georgian and Victorian architects employed so well has been adapted to so many different materials and building methods. I feel sure that if house builders required classical style buildings to be made off-site in sufficient volume this could easily be done. The reason why so much off-site buildings are so hideous is because of the taste of the designers and that is where the problem lies. Many architects like to make their buildings look original and fear being ‘pastiche’. The definition of pastiche is ‘an artistic work in a style that imitates that of another work, artist, or period’. For some reason architects always try to avoid being labelled in this way, but I feel that as with all art forms, the artist (or architect in this case) is part of a tradition stretching back thousands of years that evolves and develops over time. Generations of architects have tried to make beautiful buildings and it is worth benefiting from their knowledge. To avoid being pastiche is, in my opinion, the biggest stumbling block to the production of beautiful houses. It is a far greater obstacle than the engineering problem of producing beautiful houses off-site. If we can get to the moon and split the atom, the technical issues of making beautiful homes in a factory is well within our capabilities.

Francis Terry

Houses by Francis Terry & Associates for Halsbury Homes

(A version of this essay was first published last year by the Policy Exchange for their Building Beautiful report)