Designing for the Wingless

In The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald describes two areas on Long Island, known as the 'East Egg' and the 'West Egg', in the following terms.

"They are not perfect ovals - like the egg in the Columbus story, they are both crushed flat at the contact end - but their physical resemblance must be a source of perpetual wonder to the gulls that fly overhead. To the wingless, a more interesting phenomenon is their dissimilarity in every particular shape and size."

The gull sees a site plan, but the human sees a setting for their life carried out on the ground. Seeing from both points of view is a daily challenge for any architect or master planner. Architects need to raise ourselves from the ground to design, but we humans live on the ground, and it is from that position that architecture either succeeds or fails.

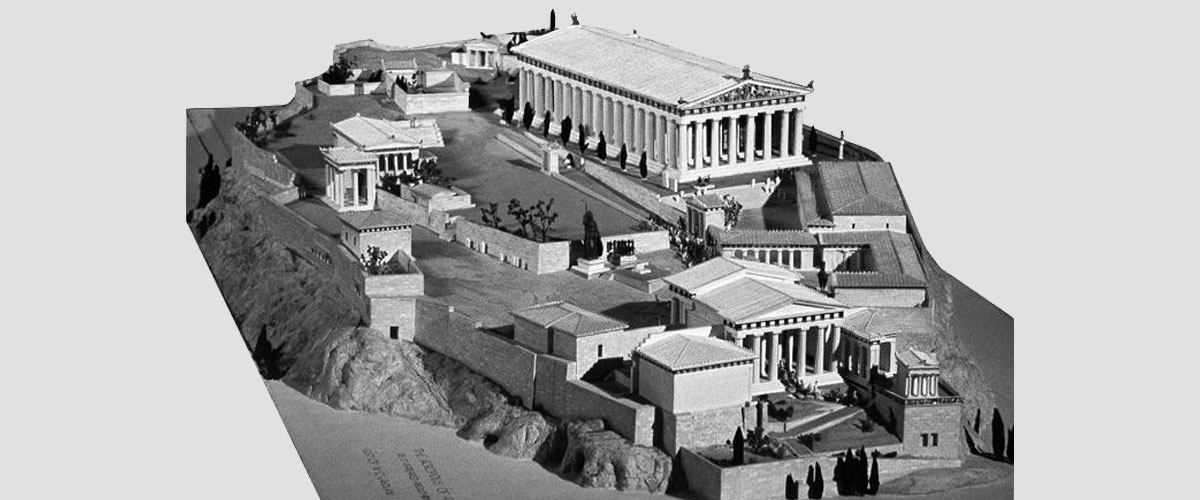

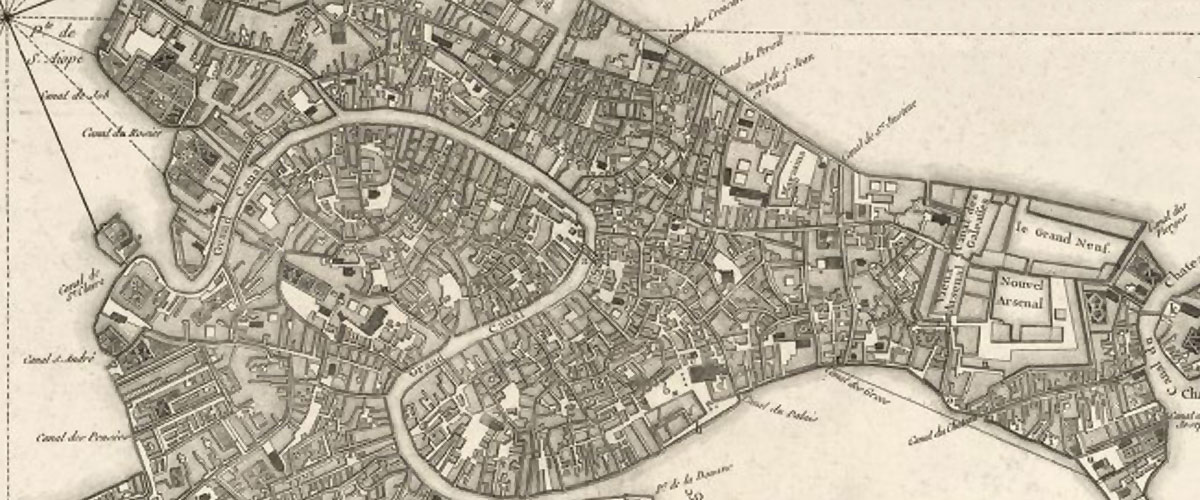

The ancient Greeks understood this when building the Acropolis. The temples are orientated in relation to the immediate topography and their position within a ceremonial sequence. There is no all-pervasive grid to orientate the buildings, the temples are disposed informally, like mahjong tiles thrown on a table. Similarly, but in a denser context, any village, town or city on a medieval street layout shares this informal layout. Venice is probably the most complete, and certainly the most exquisite example.

This way of laying out a settlement has a charm where accidental views and relationships between buildings develop and one is constantly stimulated by what may be viewed at the next corner. These are places designed from literally marking out walls on the ground, creating a similarly meandering structure which our distant ancestors would have experienced while living in dense woodland.

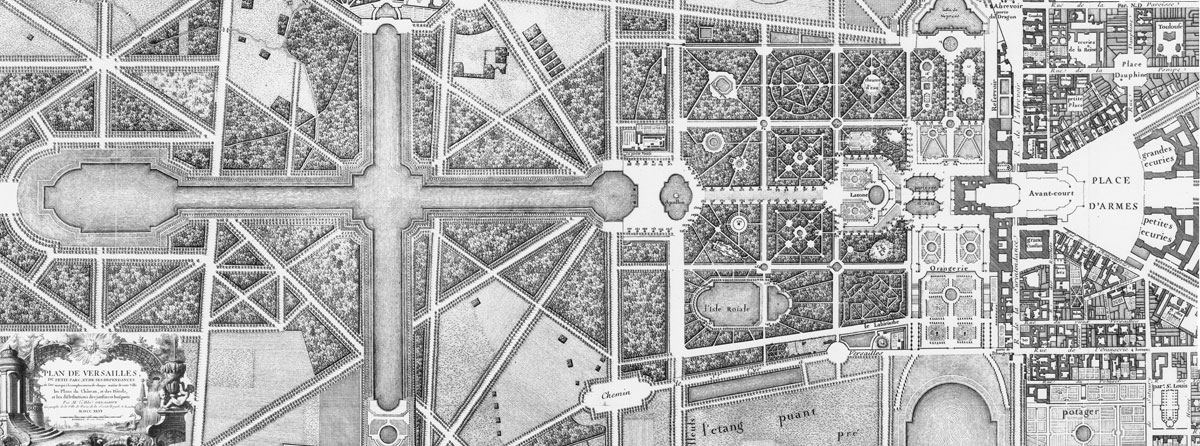

This organic way of designing came to an end with architects and their use of paper and T-squares. The subtle, traditional way of designing transformed into geometric, pattern-making on a grand scale. The gardens of Versailles are the most classic example of this, they look great from the hall of mirrors, in the palace, but walking around the garden is quite a dull experience. I'm a classicist and I love straight lines, but they have their limitations. Walking down a straight avenue to a palace is monotonous, all you see is the house getting bigger. I prefer a meandering drive which takes you on a journey of different views and picturesque moments. This is how gardens like Stowe were set out. Temples are not to be viewed centrally but glimpsed obliquely as part of a composition of trees, and landscape. Each vista is designed as a living painting which has a carefully controlled composition, in imitation of artists like Claude Lorraine and his contemporaries.

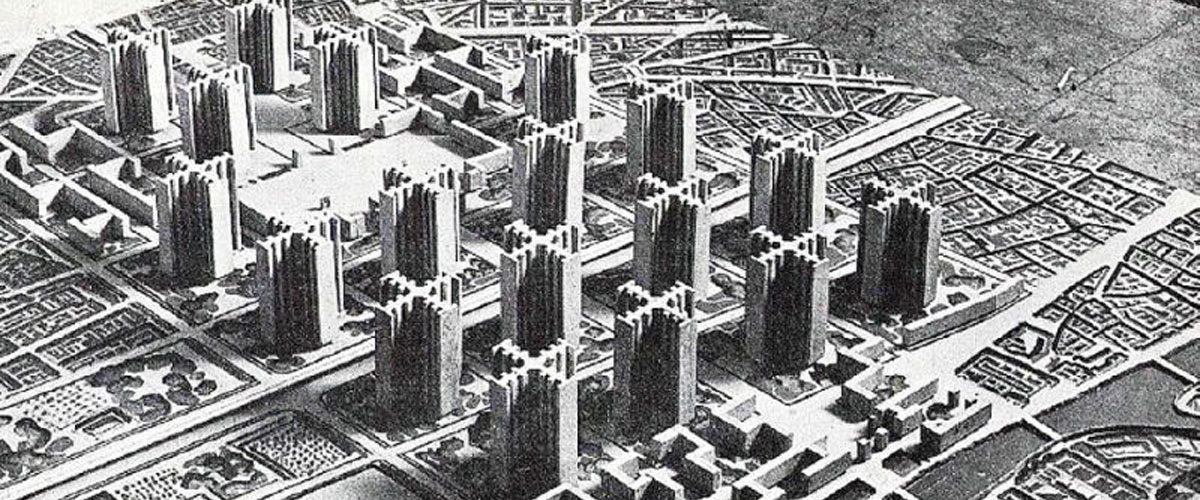

Unfortunately, these lessons were ignored by many of the modernists, resulting in Le Corbusier's disastrous approach to Paris where he intended to replace the charming medieval street pattern of the Marais with a grid of high rise towers. Made all the worse by having the towers stripped of any humanising architectural detail. Fortunately, this was not built, although the idea has been much copied since, with disastrous consequences.

Architects sometimes need to take flight to see what their work looks like from on high but they must always return their feet to the ground. Although perhaps things are looking up - one of the huge advantages of being an architect now is the ease in which one can use computer programs to produce accurate perspectives. We are increasingly using perspective to generate our designs and then altering the plans to suit. Through the use of computers, we are getting back to what architecture was before the tyranny of a set square dominated architectural production. We are now more easily able to design for the pleasure of the wingless, which is fortunate because birds are tricky clients, as Lubetkin discovered...but that's another story.