Fortune Favours the Friendly

Intro

On occasions I meet architects who think that they are, or more often should be, 'in charge' of every aspect of their buildings. These people are either very naive or deluded. They harp back to a golden age when architects were taken seriously like doctors or lawyers and paid a proper fee. They fail to grasp the essence of architecture and an easy life. The trick is to collaborate, do your bit well and don't over stretch yourself. Let others do the part you struggle with which frees you up to do the design without worrying about things that get in the way of sound architectural judgement. The RIBA and the architectural press often bemoan the inevitable eroding of the architect's role as project managers, planning consultants and contractors take away their traditional duties. It is part of a broader trend towards specialisation; Adam Smith's division of labour has at last alighted on architecture and the profession, like King Canute’s attempts to hold back the inevitable tide. Unlike many of my peers, I welcome this situation. I did not come into architecture to administer contracts, fill up planning forms or take responsibility for damp proofing, all of which I have only a superficial knowledge at best. I came into architecture to design buildings and if someone wants to take the duller yet essential supporting jobs away from me, I say, bring it on!

Collaboration comes in many forms; collaboration with clients, fellow professionals, builders, craftsmen and work colleagues.

Clients

When you think of really great structures like the pyramids, the Pantheon or Versailles, the architect's name almost seems irrelevant pitched against the titanic will of their patron. And rightly the Pharaohs, Emperor Hadrian and Louis XIV are seen as the driving force behind their most celebrated works of architecture. Seeing St Paul's cathedral as being designed by Sir Christopher Wren is really not the whole story. The idea for a classical domed cathedral, which had no precedent in English architecture, must have been the brainchild of Charles II who had seen similar buildings while exiled in France. Likewise the architectural detailing was probably designed by master masons with Wren's consent. Precious few construction drawings were done of the cathedral and very few by Wren's hand. For example, the Corinthian capitals of the lower order are amongst the most beautiful by any standard owing more to the work of sculptors in the tradition of Grindling Gibbons than Wren who was a mathematician and astronomer by training with little practical experience of sculpture or architectural ornament.

This is certainly my experience of clients; they are, for better or worse the driving force behind everything about the project. I have had clients who have educated me and changed the way I design through their perfectionism and eye for detail. Other times a client will not listen and I end up designing something, which I knew could be better, but the happiness of the client is the goal of every project.

Designers

A successful project relies on a group of designers working collaboratively to ensure the best result. Currently I am working on a house where we have a very cohesive professional team. I sit around the table with the garden designer and interior designer and between us we refine the scheme and in so doing improve it from all points of view. A certain degree of detachment by everyone is necessary so that each professional can work to the best of their ability. A well run contract is like being part of an orchestra; everyone does their part well leaving space for others to perform their role. I had a client recently who wanted a classical outside and a modern interior. For this I paired up with a contemporary designer, we established the extent of each others remit and it all worked very well. The alternative would be for me to force the client to have a classical interior against their wishes or try to design modern style interiors myself. Neither situation would have ended well.

Builders

Collaboration with builders is essential for architects, if the architect falls into the trap of feeling that he must control everything the builder does he will very soon be in deep water. The way an architect gets a good building is to only insist on what is important to him and allow the builder to do his part unhindered by the architect's half-baked ideas. An increasing amount of building contracts allow the builders to design and take responsibility for elements of work. This way of working is resented by many architects as they view it as yet another nail in the coffin of this hallowed profession. Take the issue of damp proofing, a remit increasingly given over to builders. Traditionally, architects would draw out damp proof courses, including axonometric sketches of how the various sheets of material meet on awkward junctions. The draftsman detailing these elements had probably never touched a damp proof membrane and so would know next to nothing about the practicalities of the details he was drawing. In this situation the builder has no incentive to make sure it works. His attitude will be "Mr Architect has detailed this, I know it's not going to work but what do I care, he is the person to blame, not me." A better situation is for the builder to take responsibility for damp proofing design and installation. This will motivate him to do the best job he could with the materials of his choice. The architect would need to know the visual impact of the damp proofing and that it works, but nothing more.

Craftsmen

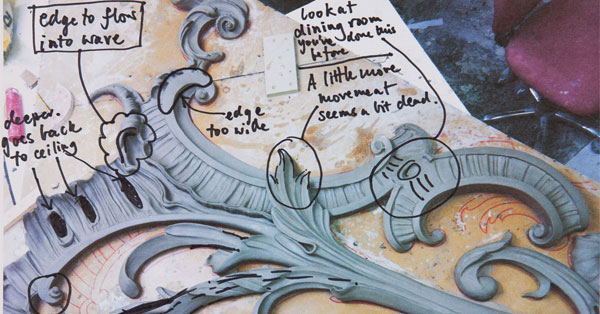

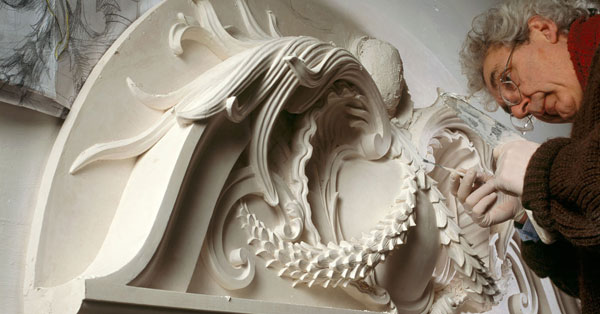

To have a successful collaboration with a craftsman, like with a builder, you need to know what to draw and equally important, what not to draw. For example, when working on full size drawings of classical ornament we often adapt our details to suit the material in which the object is to be made. For example, if it is to be cast, we think how the mould can be removed and if carved we think about how the mason will be able to get his chisel in for undercutting. I have recently discovered that this is not a good way of working, and again collaboration holds the key. It is much better to design exactly the form you want, meet with the craftsman and discuss how this can be achieved. If your detail is impossible to make, compromise then and not before. Conversely you will find that some part you thought was very hard to make is in fact very easy.

A good collaboration with a craftsman is one of the great pleasures of architecture. I recently designed a ceiling for a client in Ireland who was keen to have a rococo design in the style of the Lafranchini brothers who worked in Ireland during the 18th century. In order to do this I went with the modellers to see some Lafranchini work in the flesh. We got permission to bring tools and clay into a Lafranchini house to copy the work there. I spent some time modelling with the craftsmen, which gave me greater insight into the Lafranchini brothers work and the issues to look out for when inspecting the new ceiling. Needless to say this was a very enjoyable experience and made a huge difference to the quality of the final work.

Work colleagues

Work colleagues have a lot to contribute to the design process. Some architects feel the need to design in isolation; they shut the door and draw. The problem with this way of working is that very quickly you will not be able to see the wood for the trees, you will end up pleasing yourself but not actually doing a good piece of architecture. Good design needs to have a rational answer to all criticism. It should take on ideas from anyone, particularly people who are not part of the profession as their view is often better than those directly involved. This is very much my approach when I design. I welcome people coming in and passing comment. Some of these views are worth listening to, others not, but I value the interaction and having my preconceptions challenged.

----------------------------------------

When I was growing up, I was torn between wanting to be an artist and an architect, a common dilemma, which has faced many artistic students. Having completed my architectural qualifications and worked for some time in offices I decided to dedicate myself completely to painting. After three years I gave up and returned to architecture, the reason for this really goes to the heart of the nature of collaboration. Before this painting episode, I would see people working in supermarkets and in my rather patronising way, I would feel sorry for them. I felt that if only they could be freed from the humdrum reality of paying the rent they could dedicate themselves to some artistic enterprise of their own, perhaps writing a novel or whatever they pleased; as I began to find the life of an artist increasingly lonely I would see the same people and actually feel quite jealous. They had a purpose, they were necessary and while they did their jobs they could happily have a joke with their peers or share their stories. They were embodied in life in a way that a lone struggling artist can only dream. I wanted this connection with life, I am sure the renaissance artist working on his frescos would have been involved in a similar social endeavour, but the modern artist is a very isolated figure. I missed the office banter, the discussions with clients and builders. I missed having deadlines and feeling part of something bigger, in short, I missed the collaboration on a work of art that was too big for me to create by myself. Painting is of course one of the highest and most intense art forms, but it is small and personal, great as Vermeer undoubtedly is, his entire surviving works could easily fit in a typical self storage unit. Architecture on the other hand paints on a far broader canvas, which requires the collaboration of many differently skilled people in its execution and this is in essence the joy of architecture.

Francis Terry

(This essay was first published in The Art of Classical Details II, An Ideal Collaboration by Phillip James Dodd. Published by The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd, 2015)