Glad to be Pastiche

The definition of Pastiche is 'an artistic work in a style that imitates that of another work, artist, or period.' I imitate historic buildings, rather than inventing new styles, and with this in mind, it may seem fair game to direct the word at my work. It contains the word 'past', making it the perfect insult against Neo-Classical architects. The sound of it has a slightly cloying character, like 'serviette' or 'pulchritude', but having considered the meaning behind any criticism, I have concluded that I'm happy to be labelled this way as I believe the act of copying is an important part of creating anything. Children learn by imitation and so do grown-ups.

Pastiche originates from the Italian noun 'pasticcio' which is a pie filler or pâté made from diverse ingredients. This name was adopted in the 18th century for 'pasticcio' operas, which were a composite work or medley using portions of other composers work. Mozart's imitation of the baroque style is seen as a pastiche, and Tchaikovsky's, in turn, imitated Mozart. This tradition in music continued down to our own time, with Amy Winehouse's pastiches of classic soul and R&B. In film, Quentin Tarantino's 'Kill Bill' pays homage to Westerns as well as Kung Fu cinema. Tarantino's attitude of 'steal from everyone' is the cornerstone of the pasticheur's philosophy. Literary examples abound, as language itself evolves through endless repetition and rearrangements.

The word pastiche can be applied to all artists from Giotto to Picasso. The tradition of painting, like all art forms, builds on the work of previous generations, for example, Manet is a pastiche of Velasquez, Velasquez of Titian, Titian of Bellini and so it goes on. This practice is not confined to traditional painting; the modernists are just the same, as Picasso imitated African art and Gauguin the indigenous art from the Tahiti, while Goya influenced the Chapman Brothers.

Art without the influence of previous work is less worthy because it is not part of a long, artistic tradition which society understands. It is not just a matter of stealing. A work of art, within a tradition, automatically develops the language, as it is impossible to copy anything exactly. This is particularly so in architecture, where client's demands, building regulations and a myriad of other variables all conspire to produce an original work. These alterations further enrich tradition for the architects of the future.

The whole history of classical architecture is based on pastiche as each generation copies from earlier buildings and historic pattern books. I copy the Georgians, the Georgians copied Palladio, Palladio copied the Romans, the Romans copied the Greeks, the Greeks copied the Babylonians and the Babylonians copied the Egyptians. By this analysis, the greatest works of architecture including the Parthenon, and the Pantheon - as well as simpler buildings, like Georgian terraces or Haussmann's Paris, are all pastiche. Unsurprisingly, I am very happy to be a member of this club.

Avoiding pastiche prevents playfulness of architecture, reducing buildings to bland conformity. Buildings like Brighton Pavilion, which is a medley of Chinese, Indian and Gothic architecture would not be possible if Nash was trying to avoid pastiche. Architecture should tell stories and transport people to another time and place. I sometimes feel that the people who hate pastiche have a joyless puritanical streak, which prevents them from appreciating the architecture to the full.

Judging architectural merit by whether it is pastiche or not is flawed because the ability to know which building came first is essential to knowing which building is original and which is a pastiche. The problem is that most people have no idea of the chronology of architecture and so are unable to discern which is pastiche and which is not. People see buildings and respond to them emotionally with the heart rather than academically with the head.

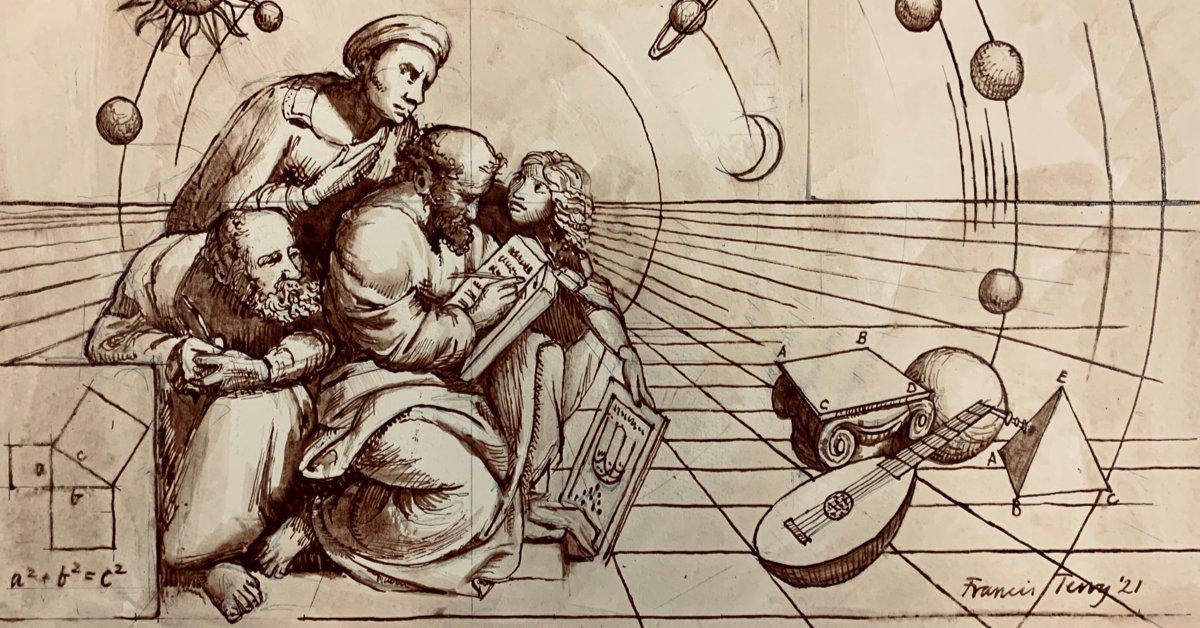

The fear of being pastiche runs deep with architects and therefore work is judged on how innovative it is rather than its intrinsic merit. I think that architects should not aim at originality but try for the far harder goal of beauty. Beauty in building is so rare, architects need all the help they can get to achieve it. If imitation helps accomplish this scarce quality, architects should roll up their sleeves, don their aprons and cook up some delicious pasticcios.

Francis Terry

Photography by Nick Carter.