The Use of Scamozzi Ionic in Georgian Architecture

The use of the Scamozzi ionic in Georgian Architecture

As a practicing classical architect, I have had a number of clients who have wanted their houses to look like the work of the English Palladians of the Georgian era rather than Palladio himself. From this, I started to notice that the work of the English Palladians does not follow Palladio's architectural details. One particularly striking difference was the choice of ionic capital. I therefore decided to analyse the extent to which Palladio influenced the English Palladians, through the prism of their choice of ionic capital. This small but significant detail can be seen to reflect wider Palladian attitudes.

The term Palladian is incredibly broad. It encompasses architects from the sixteenth century up to the present day, who claim influence from Palladio's buildings and writing. For the purposes of this essay, Palladian is used to refer to the architects who came to prominence in the early Georgian period, from 1715 until the late 1730s. The Whig majority, who came to power on the accession of the first Hanoverian monarch, George I, rejected the exuberant Baroque style associated with the rule of the Stuart kings. Instead, the circle around Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, embraced the restrained classicism of Ancient Rome, as interpreted by Palladio. The year 1715 marked the publication by architect Colen Campbell of the first volume of his manifesto for classical design, Vitruvius Britannicus1, which drew heavily on both Palladio and the Roman architect Vitruvius. It also saw the publication of the first English translation of the whole of Palladio's treatise on architecture, I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura2, edited by Giacomo Leoni3. This short period produced a very recognisable style, but despite its name, in the use of the Ionic capital, the Palladians took nothing from Palladio.

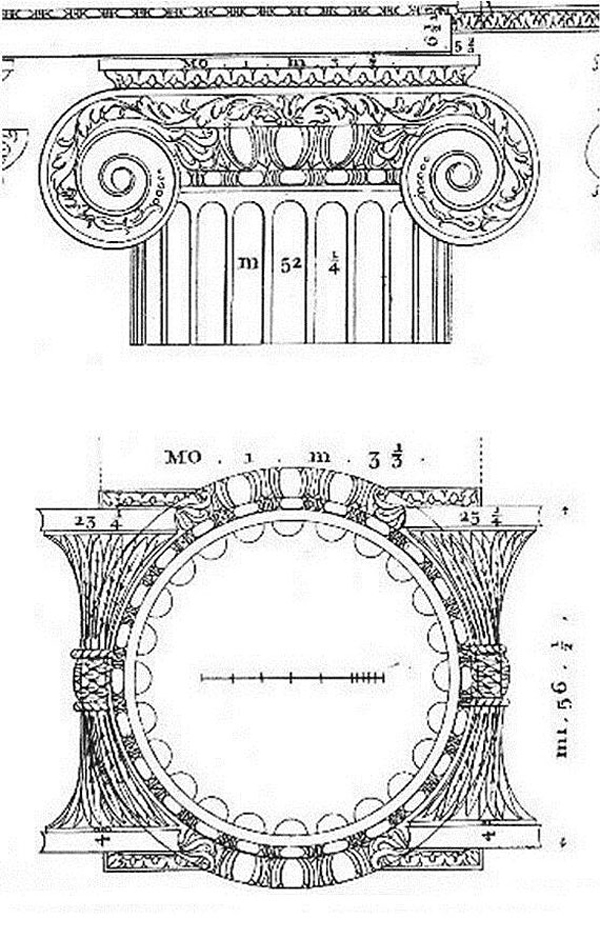

Palladio, both in theory and practice, advocated the use of the conventional Ionic capital. For any architect trying to follow Palladio, his direction is very clear. Palladio devotes an entire page of his Quattro Libri to an illustration of Ionic capitals4 (Fig.1) and reflected this theory in his practice. Palladio's parallel volute capital consists of the spiral, scroll-like volutes on a flat front and back, with bolsters joining them on the sides, following the conventional structure of the capitals in ancient Greece and Rome. Palladio's Ionic is a standard Roman Ionic, like the examples at the Theatre of Marcellus in Rome. Palladio used this capital on almost all his secular buildings, from the Basilica, Palazzo Chiericati and La Rotonda in and around Vicenza to La Malcontenta, also known as Villa Foscari, in Mira5.

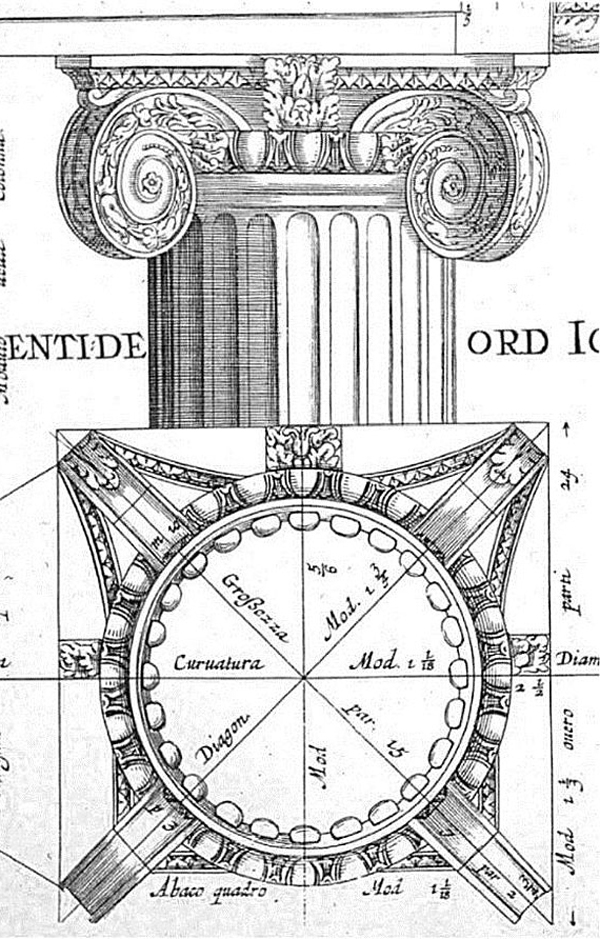

In contrast, the English Palladians generally used the Ionic capital illustrated by Palladio's disciple Vincenzo Scamozzi (1552-1616) in his book L'Idea dell'Architettura Universale. (Fig.2)6

The Scamozzi Ionic capital looks very different. As a diagonal volute capital, the four volutes are positioned at 45 degrees to the centre line, making all faces the same. Scamozzi claimed that his version of the Ionic capital was, "different from any other [Ionic] capital ever invented", although he did acknowledge that his plan and elevation had a mixture of sources: "...partly copied from antiquity, partly based on Vitruvius and for the rest is a design I have invented and used"7. The most famous example from antiquity is the Temple of Saturn8 in the Roman Forum (Fig.3).

There are also examples of this type which were salvaged and used in Early Christian churches, such as Santa Maria in Trastevere9, although many of these may be the top half of a pre-existing composite capital, rather than a consciously designed Ionic order. Many of the most significant buildings by the English Palladians, from Campbell to Henry Flitcroft and William Kent, use the Scamozzi Ionic, rather than following Palladio's example. So, for example, Campbell used the diagonal volute Ionic capital on the porticos at Mereworth Castle and Houghton Hall (Fig.4), two of his most significant buildings, while Flitcroft adopted it on the portico at the church of St Giles-in-the-Fields and the front façade of Woburn Abbey. Kent used the Scamozzi Ionic extensively in the Temples of Venus and of Ancient Virtue at Stowe; (Fig.5) in London in Whitehall on the north front of the Treasury building and the Horse Guards Building; on the front façade and hall at Raynham Hall, Norfolk, and on the grand staircase at 44 Berkeley Square, London. In addition, numerous chimney pieces by Kent and Isaac Ware also use the Scamozzi Ionic capital. Kent was the only Palladian to use both versions, incorporating Palladio's conventional Ionic capital in the Marble Hall at Holkham Hall (Fig.6), the Ionic Temple in the garden of Chiswick House and the Cupola Room at Kensington Palace. Of these three examples, the Cupola Room capitals bear the closest resemblance to Palladio's version. The others are recreations of the Roman Temple of Fortuna Virilis, which could have been found in Palladio's Quattro Libri10, but could equally have been found in Antoine Desgodetz's Les Edifices Antiques de Rome11, as it was illustrated in both.

The primary reason for the Palladian’s choice of Ionic capital, is likely to have been their reverence for the example set by Inigo Jones. Jones was the leading royal architect under James I and his successor, Charles I. He pioneered a classical style of building in Britain, inspired by ancient Rome and his near contemporaries; Palladio and Scamozzi. Campbell idolised Jones calling him “immortal” and said in his introduction to Vitruvius Britannicus: “...our architect (Jones) is esteemed to have out-done all that went before...”12. Meanwhile Lord Burlington commissioned sculptor Michael Rysbrack to design statues of Palladio and Jones, which he positioned symmetrically either side of the entrance stair to Chiswick House, suggesting he regarded the two architects as equals. Kent published a large book illustrating the designs of Inigo Jones, with drawings by Flitcroft, in 172713. Jones appears to have been the first British architect to use the Scamozzi diagonal volute Ionic capital. Until Jones, Ionic capitals in England seem to follow the conventional parallel type. After Jones, English architects used the Scamozzi style almost exclusively, up until Robert Adam in the mid-eighteenth century. Jones used the Scamozzi Ionic on most of his remaining buildings, as can be seen at the Banqueting House, Whitehall, London (Fig.7); the Queen's House, Greenwich; the Venetian window at Wilton House in Wiltshire; Lindsey House at 59-60 Lincoln's Inn Fields and Stoke Park in Northamptonshire. He once used the Palladio Ionic in the interior of the Banqueting House, on the ground floor of the main hall, but perhaps because it was an interior, it went unnoticed.

There are several possible reasons why Jones chose Scamozzi over Palladio's conventional ionic. Jones's work is radically different to his contemporaries, drawing the conclusion that he was willing to consider different solutions compared to the Jacobean Mannerism of the time. His predecessors, such as Simon Basil and Robert Smythson, used the conventional Ionic ubiquitously, as can be seen at Hatfield House, Hertfordshire, where it features on everything from the grand scale south facade first floor order, to numerous smaller scale items like chimney-pieces, balusters and table legs.

However, the main reason may well have been purely practical. A huge advantage of the Scamozzi capital compared to the conventional Ionic is that all four elevations are identical, which makes it far more appropriate for use where a side elevation, as well as a front elevation, will be on view. With the conventional Ionic capital, the sides with a bolster would never be acceptable for a principal elevation. The Ancient Greeks resolved this problem by turning the volute at the corner of the building at 45 degrees to the centre line. Examples are found at the Erechtheum (Fig.8), in Athens, and later by the Romans at the Temple of Fortuna Virilis in Rome. When Palladio faced the same problem, he copied this solution, for example at the Basilica and La Malcontenta. This solves the problem, but is far from satisfactory, as the two end capitals are asymmetric and different from the rest. Though slightly later than the Palladians, Sir William Chambers acknowledged the limitations of the conventional Ionic capital, compared to Scamozzi's design. In his 1759 Treatise on the Decorative Part of Civil Architecture he wrote: "...the angular capital invented by Scamozzi, or imitated and improved by him, from the Temple of Concord, or borrowed from some modern compositions extant in his time, ought to be employed; for the distorted figure of the antique capital, with one volute straight and the other twisted, is very perceptible, and far from being pleasing to the eye."14

Jones was willing to study the capitals used by Italian architects both ancient and modern, by making two trips to Italy. During the first trip, from 1598 to 1603, Jones met Scamozzi and purchased a copy of Palladio's Quattro Libri from him15. After this meeting, Jones wrote that Scamozzi "hath resolved me in this in the manner of voltes"16, suggesting that they had discussed Scamozzi's innovative Ionic capital. During his second tour of Italy in 1613, Jones annotated his copy of Quattro Libri while visiting Roman ruins and could also have seen a real-life example of Scamozzi's Ionic capital when he stayed in Villa Molin, designed by Scamozzi17.

Back in England, Jones referred to a variety of sources from his extensive library, which included architectural treatises by Alberti, Serlio, Vignola, Vitruvius and Scamozzi, as well as Palladio. He formed his own style as a mixture of all his preferences. He had no desire to be a man of one book. We can tell that Jones also studied his copy of Scamozzi's L'idea dell' Architettura Universale closely, and tried to relate the illustrations to the Roman monuments he had visited, by his annotations in the margin. Jones initially wrote next to Scamozzi's elevation for an Ionic capital, "... capital is taken fro(m) y temple of concordia...", but then crossed out "concordia" and replaced it with "Fortuna"18.

Using a radically different Ionic must have seemed an attractive way for Jones to separate himself from the English architects of the time, and display his knowledge of ancient and contemporary Italian architecture. If Scamozzi had invented this capital as perhaps Jones thought, he would have been using the latest in classical design. Claude Perrault, for example, later referred to Scamozzi's design as the 'modern' capital, in his architectural treatise, 'The Ordonnance des cinq especes de colonnes', published in 168319. However, Jones did not view Scamozzi as an equal to Palladio, referring to him as 'purblind'20 but perhaps he was influenced by him more than he would care to admit.

Continuing throughout the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth century, Ionic came to mean Scamozzi's Ionic. Sir Christopher Wren, Sir John Vanbrugh, Thomas Archer and Nicholas Hawksmoor only used the Scamozzi diagonal Ionic rather than conventional type. Many of the great buildings of this period - Chatsworth, Seaton Delaval Hall, Trinity College Library, Cambridge, Peckwater Quad in Christ Church, Oxford - all use the Scamozzi Ionic. During the Restoration, from 1660, the continued use of the Scamozzi Ionic may also have been a way of showing allegiance to the Stuart crown, given that before the Civil War Inigo Jones had used it on royal buildings including the Banqueting House and the Queen's House. The Scamozzi Ionic was also popular with Dutch, as seen at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, so there could also be a connection with William of Orange. Subsequently publications during the eighteenth century all feature the Scamozzi Ionic capital, rather than Palladio's version. In 1732, James Gibbs published The Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture, which set out methods of drawing the Classical orders, including the Scamozzi Ionic. The designs were widely circulated via cheaper, smaller pattern books for craftsmen and builders, such as those published by William Halfpenny from 1724, William Salmon from 1733 and Batty Langley from 1738.

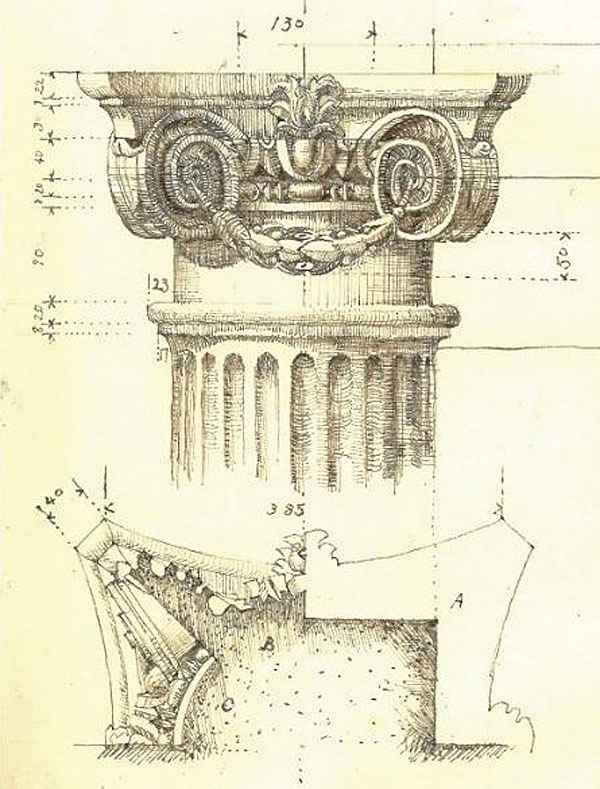

However, I suggest that the Scamozzi Ionic capital is too sculptural to carve from a pattern book alone. Masons must have seen actual examples, brought back from Italy, on which they could base their new capitals. This seems particularly likely because English 17th and 18th century examples generally have volutes that are trapezoid, rather than rectangular shaped, in plans, which Scamozzi illustrates. Also, the volutes are heavily undercut which is not a level of detail shown in pattern books. These two variations from Scamozzi, make the capital like many Roman baroque examples, as can be seen at the Raimondi Chapel and the porch at Santa'Andrea al Quirinale both in Rome by Bernini (Fig. 9).

This suggests a relatively recently carved baroque example may have found its way to England.

At a time when architects made few, if any, site visits, and architectural drawings were far less comprehensive, builders had to get on with the job with very little intervention from architects. Instead, builders would have relied on masonry firms that specialised in carving capitals following the familiar and accepted norm. Through decades of repetition, craftsmen built up experience at carving beautiful versions of the Scamozzi Ionic capital, which must have contributed to its success. The Palladians worked in this context - where the Scamozzi ionic was what everyone considered to be an Ionic order. If they were really serious about following Palladio, they could easily have consulted their Quattro Libri and changed the capitals on their new buildings, but they consciously decided to stick with convention. This is made clear by the fact that Campbell in Vitruvius Britannicus renders the Scamozzi Ionic instead of conventional one on all Ionic buildings including his own. It is therefore not a case of builders failing to follow architects' instructions. The Palladians, with their admiration for Jones, must have preferred the capital Jones would have chosen, and hence used the Scamozzi Ionic.

They were in effect following Palladio through Inigo Jones's eyes. Though they were keen to show inspiration from Palladio, Jones was their ultimate guide. Campbell took this to an extreme with his design for Houghton Hall, which is a combination of two buildings by Jones. The hall is the cube room at the Queen's House Greenwich and the front elevation is a copy of Wilton with an added portico21. In Vitruvius Britannicius, Campbell was keen to show the greatness of the English classical tradition. He wished to establish England as a world leader in architecture, to rival the Italians, who he felt had lost their way by adopting the Baroque. The English Classical tradition in Campbell's time was a small and minor artistic movement compared to the architecture in both France and Italy. He needed to make a tradition out of very limited material. As initiated by Jones, the Scamozzi Ionic was established throughout the course of the seventeenth century. It became a key element in creating an English tradition, of which he felt a part. To return to Palladio for a more authentic capital would make a break in a fragile and unsubstantial tradition. Campbell viewed some elements of Baroque as a mistake, describing the works of Bernini and Fontana as, "affected and licentious", and the designs of Boromini as endeavouring to "debauch Mankind"22, but the Scamozzi Ionic had the Jonesian pedigree to be accepted as part of the grammar of English classicism.

Based specifically on their choice of Ionic capital, it seems that the Palladians did not follow Palladio. The Scamozzi capital, as used by Inigo Jones, was the accepted norm and the Palladians saw no great need to change convention. In purely practical terms, builders would tend to use the Scamozzi Ionic as the default capital, because masons were set up to produce them, and clients were used to seeing them. Either way, the Scamozzi Ionic was used. On this issue the Baroque and the Palladians are generally indistinguishable and the separation between the two movements seems somewhat forced. For example, either Campbell or James Gibbs could have designed the Scamozzi ionic portico, at Houghton Hall, and the result would be almost identical, despite the architects being from rival factions. Categories in art history are never clearcut. In so far as there is a need to separate the Baroque Tories from the Palladian Whigs, Palladian may be a confusing term. Perhaps Neo-Jonesian would be more accurate.

Francis Terry

References

- Vitruvius Britannicus or The British architect : containing the plans, elevations, and sections of the regular buildings, both publick and private, in Great Britain, with variety of new designs (London 1715-1717).

- First published in Venice, 1570.

- English translation edited by Giacomo Leoni The architecture of A. Palladio in four books (London, printed by John Watts, 1715-1720).

- Illustrations of Ionic capital in Book I, Chapter 16, pages xvi-xx in the Isaac Ware edition (London, 1738).

- Other secular examples where Palladio used the conventional Ionic capital include Palazzo Iseppo da Porto in Vincenza, Villa Chiericati in Vancimuglio, Villa Pisani in Bagnolo, Palazzo Antonini in Udine, Villa Badoer in Fratta Polesine, Villa Cornaro in Piombino Diese, Villa Barbaro in Maser, Villa Sarego in Santa Sofia di Pedemonte and Palazzo Barbarano, Vicenza. He also used it on the convent of Santa Maria della Carita in Venice.

- Illustration of Ionic Capital in Book VI of Scamozzi's L'Idea dell' Architettura Universale (Venice, 1615).

- Quotes from Scamozzi's commentary on the illustration of the Ionic Capital, as above.

- Temple of Saturn was also known as the Temple of Concord, and referred to as such by Palladio in I Quattro Libri dell' Architettura Book Four, plate XCIV and page 109.

- I am grateful to Calder Loth for drawing my attention to this example, in his post on Classical Comments: The Scamozzi Ionic Capital (The Classicist Blog, The Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, New York, 1 September 2011).

- Book IV, illustrated page xxxii and xxxiii of the Isaac Ware edition of 1738.

- Plates I to III of Chapter IV, Les edifices antiques de Rome (Paris 1682). Reprinted 1729 and 1779, so increasing its influence on the Neo Classicists.

- As in footnote 1 above, Introduction, page 1.

- The Designs of Inigo Jones, consisting of Plans and Elevations for Publick and Private Buildings (London, 1727).

- William Chambers, A Treatise on the Decorative Part of Civil Architecture (London, 1759), page 55.

- Jeremy Filet, Representations of Inigo Jones's Banqueting House: Development of Sketches and Architectural Symbolism, published in Revue de la Société d’études anglo-américaines des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Issue 72, 2015.

- As cited by Filet above, from Howard Burns Note sull'in.esso di Scamozzi in Inghilterra: Inigo Jones, John Wegg, Lord Burlington. Vincenzo Scamozzi, 1548-161. Eds. Franco Barbieri and Guido Beltramini (Verona/Vicenza, 2003) page 129.

- Page 102, 'Inigo Jones and the European Classicist Tradition' by Giles Worsley, 2007.

- I suggest that Jones had Palladio open at the same time. Palladio's temple of Concord seems a very plausible precedent as it uses a Scamozzi ionic (four identical elevations with the volutes on the corners), but the abacus and echius profiles and proportion are from the temple of Fortuna Virilis in ancient Rome. Fortuna Virilis adopts a conventional ionic, but it does have the isolated corner volutes at 45 degrees at the very corners. If these corner volutes were used on all volutes, it would create a Scamozzi Ionic.

- I am grateful to Stefano Fera for this observation.

- Annotations by Inigo Jones on his copy of Palladio's Quattro Libri include: "This secret Scamozzi being purblind understood not". As cited on page 96, 'Inigo Jones and the European Classicist Tradition' by Giles Worsley, 2007.

- Robert Tavernor, Palladio and the Palladians (London, 1991), page 161.

- Campbell Vitruvius Britannicus (1715-1717) page 1.