Palladio: The One Trick Pony

Palladio-mania is just going too far. Last year I was invited to two Palladio parties on the same evening, one was at the RIBA and the other at the Italian Embassy. Wherever I look I see articles, symposiums, exhibitions, publications, parties and even a church service to celebrate the great man's 500th anniversary. As a Palladian I should be pleased, but it is with a great sense of ennui that I sit down to write in praise of my favourite architect. I am also surprised by his universal acceptance, because by contemporary taste, he should be derided as a backward looking plagiarist with no ideas of his own.

Most of the articles on Palladio are at pains to show how innovative and cutting edge he was. They miss the point. Despite his innovations Palladio was deeply conservative, so much so that he went to Rome and took measurements from Classical buildings so that he could copy them. He then returned to the Veneto and foisted scaled down versions on the Venetian bourgeoisie with philistine disregard for Classical iconography. He used pediments on domestic buildings; a form strictly reserved for gods and was the beginning of the end for Julius Caesar when he put one on his house.

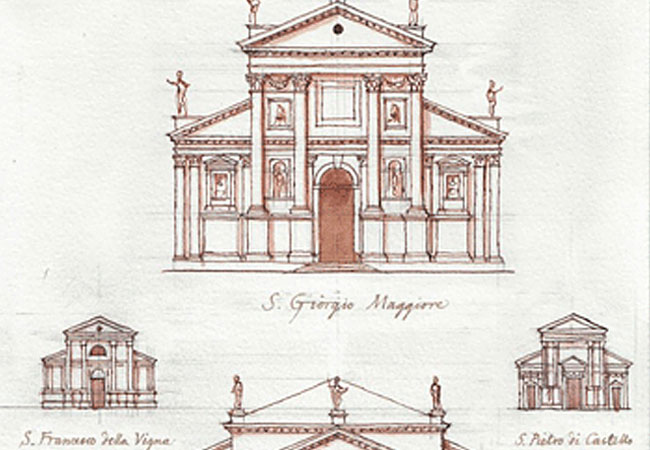

Originality was not one of Palladio's fortes. Of the many villas he designed, the facades all conform to a simple pattern. This is:- a central pediment, with or without columns below, framed symmetrically by two simpler bays with windows and steps to the front. You can see this pattern at:- The Villa Rotunda, Malcontenta, Emo, Cornaro, Farni, Saraceno, Caldogno, Poiana, Badoer, in fact nearly all of them. When he did not use this formula, like at Villa Sarego, the result was a disaster. The same could be said of all his churches in Venice. They all consist of a large central pediment with four columns framed symmetrically by two half pediments. If you stare across to the Giudecca you can see two in one eye full. Palladio was the ultimate one trick pony.

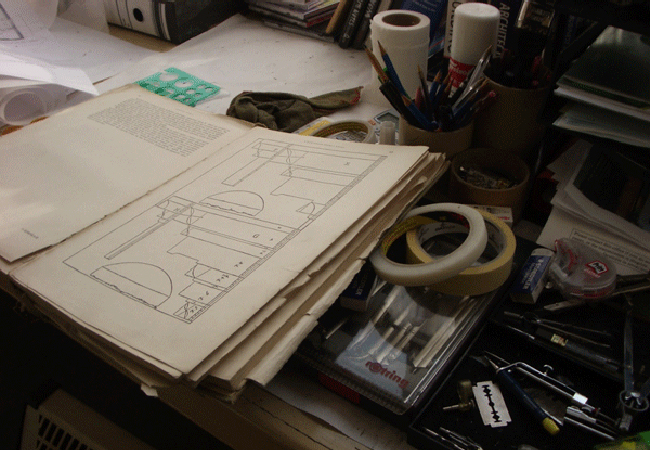

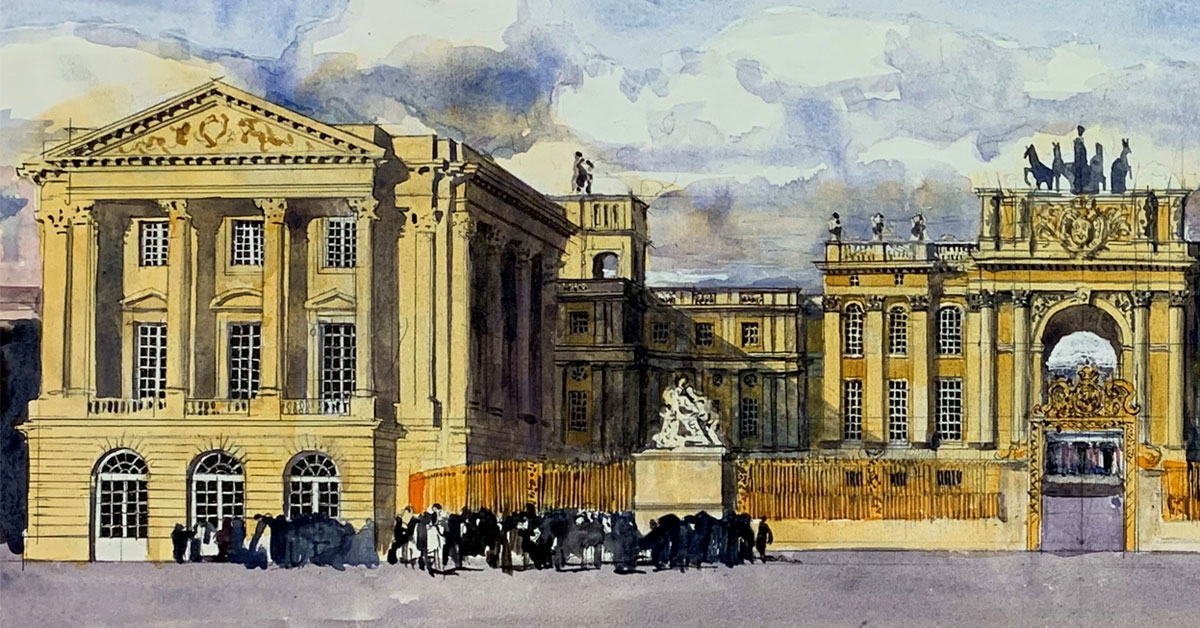

Palladio would have been almost forgotten if it was not for his 4 books on architecture. This book shows how to do classical architecture as well as illustrating Palladio's own buildings and the Roman remains. Talented contemporaneous architects like Sansovino and Sanmicheli, who wrote nothing but produced many great buildings, are relatively unknown. The 4 books gave Palladio his place in history far more than his buildings could ever have done. It is an amazing treatise, without question the greatest pattern book of the Renaissance. We use it in our office on a daily basis, for anything from sizing a door architrave to spacing modillions on a pediment. It is a five hundred year old cookbook whose recipes still taste good. The other treatises of the Renaissance, like Alberti, Serlio and Vignola, rarely see the light of day but our many copies of Palladio's are all dog-eared with broken spines through over use. Palladio's 4 books have been used ever since their publication and have influenced architects as varied as Bernini and Jefferson. With most great architects, say Le Corbusier, Lutyens or Mies, their own greatness is indisputable but their followers are an embarrassment. Because of the 4 books, Palladio's followers often transcended him. With the English Palladians in the 18th century, Palladio's crude farmhouses were rendered in stone with an eye for craftsmanship often absent in the master's work. No Palladio villa compares to the sheer 'wow' factor of Holkham Hall with its 40ft cube stone hall. Part of the cleverness of the 4 books is that it has little advice about construction. This means that the proportions and decorative motifs are followed but different cultures, locations and epochs can re-interpret Palladio for themselves. No other book since has had the audacity to claim it knows the secrets to beauty with such conviction and success. Other attempts like the Modular by Le Corbusier are solely viewed as a piece of history with no practical relevance. Many architects, even today, use the 4 books.

To enjoy Palladio, you need a different attitude to architecture. Art History is the study of seminal art and not good art. Palladio was not the beginner of anything, when his contemporaries were producing mannerist buildings under the shadow of Michelangelo, Palladio was going further back to Bramante, and he was passe in his own time. The appreciation of Palladio is not about innovation or cutting edge attitudes - it is instead the architecture of politeness and good taste.

The exhibition is bound to look beautiful, but with Palladio as the subject it would be hard to go wrong. The only aspect I have some reservations about is including fashionable Modernists as Palladio's heirs. This seems to subscribe to a now disproved theory propagated by Rudolf Witthower, who suggested that Palladio was the first architect with a taste for all things white and minimal. This is inaccurate, as Palladio loved ornament and colour. When he praised Sansovino's Library in St Mark's Square the words beauty and ornament are almost synonymous. It is a common problem for historians to reduce an artist to a single idea. An architect of Palladio's status cannot be broken down so simply. This was a man who on the one hand followed the rational humanism of ancient Greece - as well as believing in purgatory, indulgences and the magical powers of holy relics. For this reason it would be better to let the work stand alone so that the public could make up their own minds about the Raphael of architecture.

Francis Terry

(This essay was first published in the RIBA Journal - January 2009)