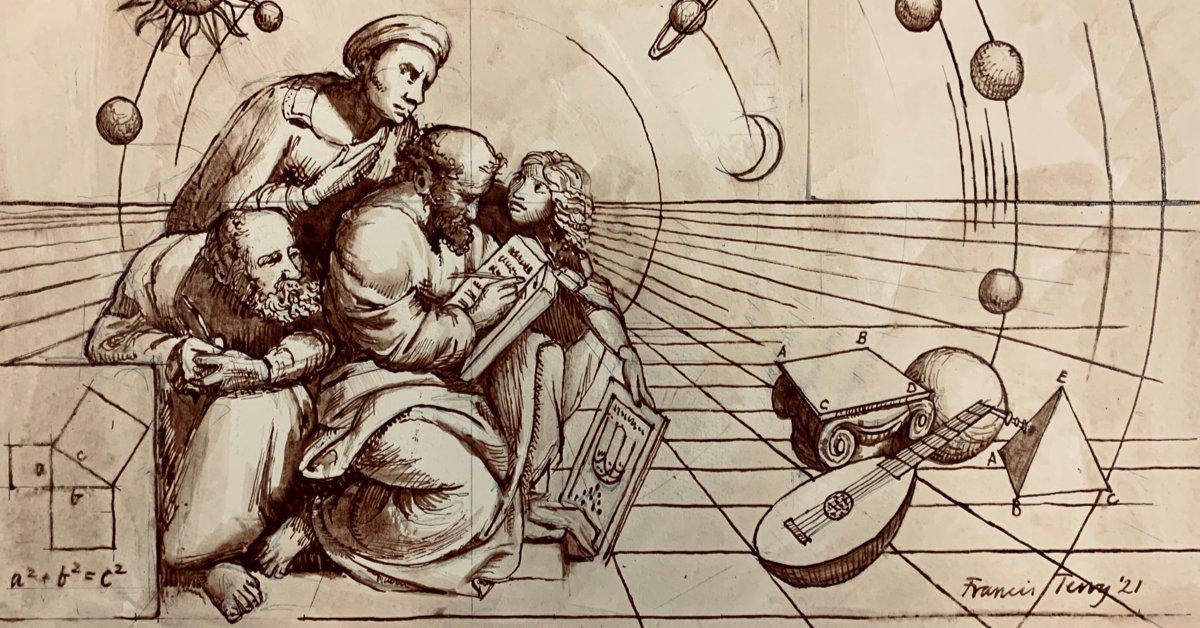

Proportions in Architecture and Music

Architects for millennia have sought to find rules to determine the proportions of every aspect of a building. A window, for example, can look too narrow and thin or conversely it can look squat and fat. How can we work out the right proportions? Is there a ratio of height to width which is perfect? Many architects throughout time have felt there are mathematical formulae to achieve the right proportions. This was a particular interest of Renaissance theorists including the Florentine architect Alberti (1404-72) who saw an equivalence between musical and architectural proportions.

“I am every day more and more convinced of the truth of Pythagoras’s saying, that nature is sure to act consistently and with constant analogy in all her operations: from whence I conclude, that the same numbers, by means of which the agreement of sound affects our ears with delight, are the very same which please our eyes and our minds.”

- The Ten Books of Architecture by Alberti book IX Chapter V

The basic maths behind musical harmony has a clarity and simplicity which appealed to the Renaissance mind. If you take two violin strings under the same tension, with one half the length of the other, and then pluck them both, the difference in pitch is an octave which sounds beautiful. In mathematical terms what you are really enjoying is the ratio of 1:2. If the strings are in a relationship of two to three you have a ‘fifth’ and if they are in a relationship of three to four it will be a ‘fourth’, all beautiful sounds as a consequence of being specific and exact mathematical ratios.

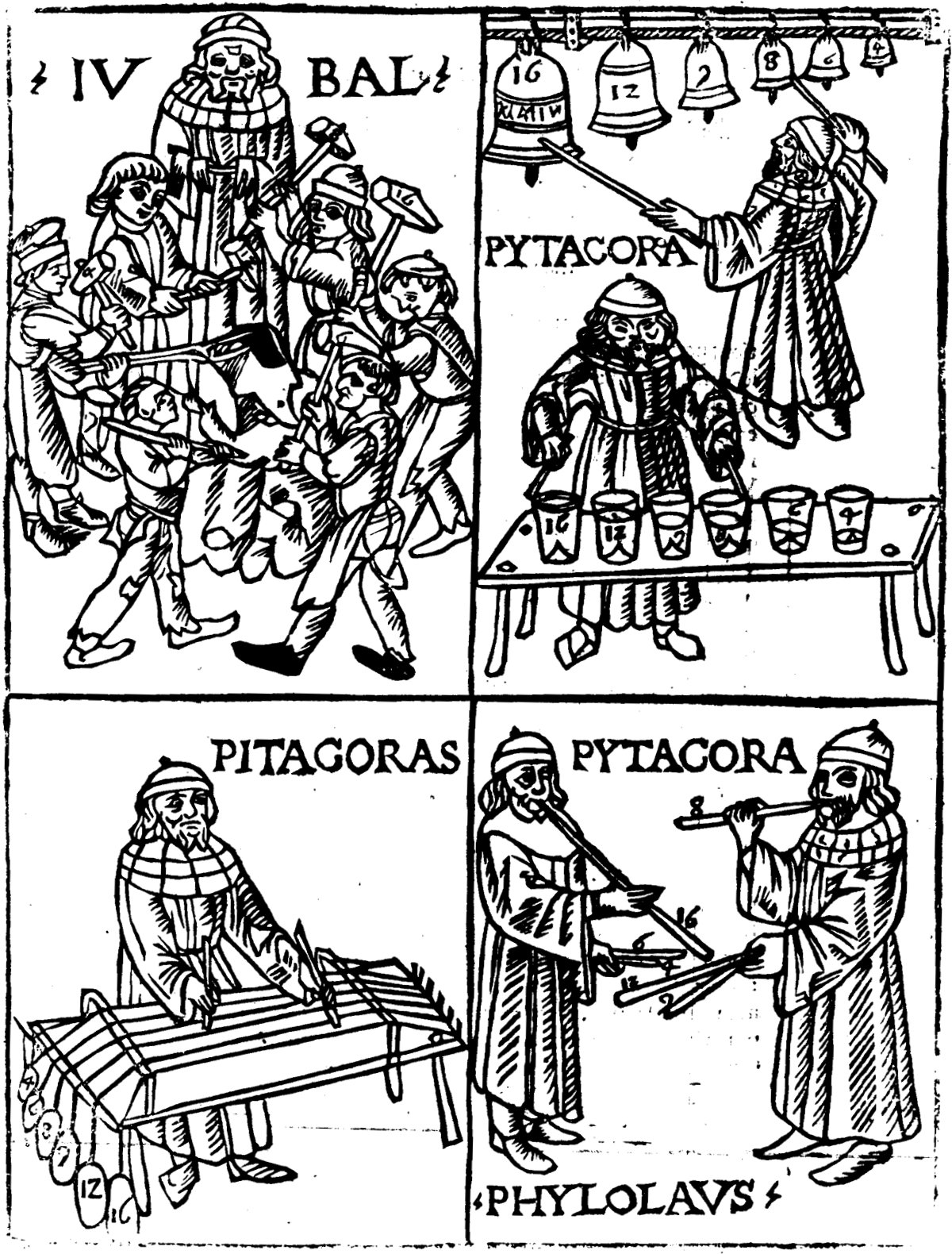

It is not just with strings that these ratios can be observed. The same patterns can be seen in different sized bells, different lengths of metal pipe in brass bands or church organ and the different sizes of wood blocks for a xylophone. The maths throughout these various ways of making different pitches of sound is the same and so they work with each other. If, for example, a trumpet player was to blow down a long brass tube he or she could make the notes of an arpeggio. This wind instrument’s arpeggio would fit exactly into the previously mentioned octave of the stringed instrument, if they are tuned to the same pitch.

As Alberti states, these ideas ultimately go back to the great philosopher and mathematician Pythagorus in the 6th century BC. He became aware of this when he walked past a blacksmith’s forge and heard the different pitches of the banging on anvils with different sized hammers. When some hammers banged at the same time, they sounded harmonious and others not. He then worked out that the hammers which achieved a pleasant sound were the ones which had a harmonic relationship between each other. For example, if one hammer was exactly twice as heavy as the other, that would produce an octave. He then went on to discover the basic maths of the musical instruments of his day. Through this he came to believe that the same simple number ratios and proportions embodied absolute truth about the harmonic structure of literally everything on earth. But Pythagoras did not stop there, he also was convinced that the same numbers and ratios were consistent throughout the whole universe.

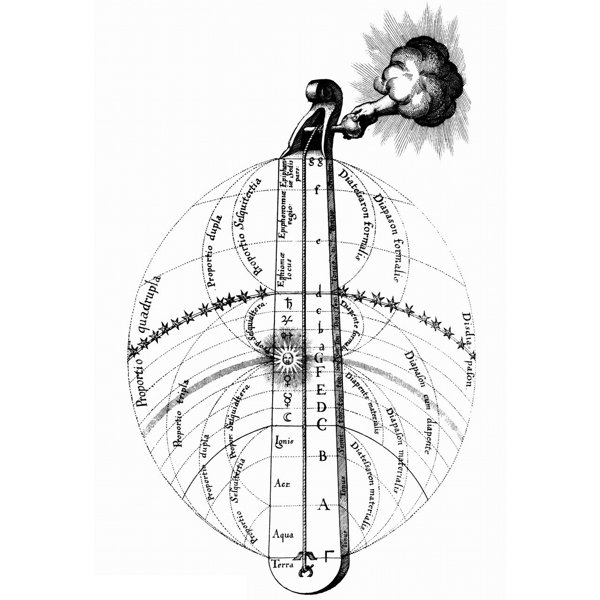

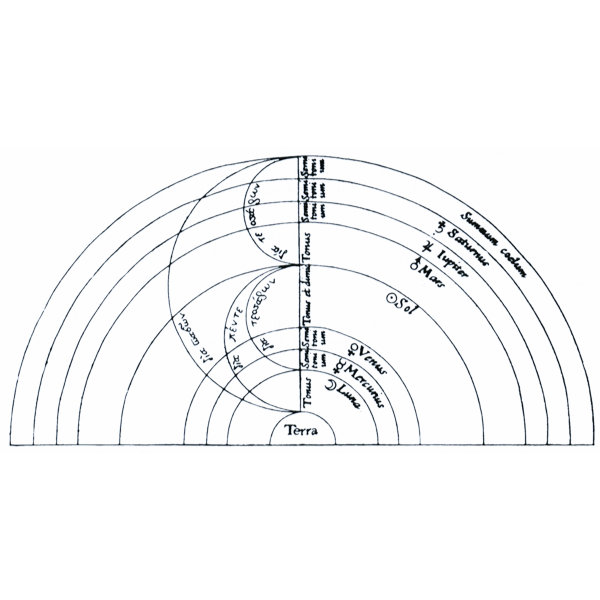

“If earthly objects such as strings or pieces of metal make sounds when put in motion, so too must the moon, the planets, the sun and even the highest stars. As these heavenly objects are forever in motion, orbiting the Earth, surely they must be forever producing sound.”

This idea, known as the ‘Music of the Spheres’, is the belief that the planets and moon spin on their obits, emitting a hum, which is inaudible to us but if we could hear it, it would be some sort of celestial music expressing the perfect harmony of the universe. The planets which are further away were thought to make a lower hum than the ones closer to earth, it was as if the universe was one massive lute or harp.

How wonderful it would be to believe that certain proportions embody timeless irrefutable truths which are consistent throughout nature, music and architecture. It is so satisfyingly neat… but is it true?

Certainly, we still look for magical formulae to explain the complexities of the universe and this is as true for Pythagorus as it is for Einstein. In music the octave, the fourth and the fifth still sound beautiful and are used by musicians both ancient and modern. But for architecture, does the analogy work?

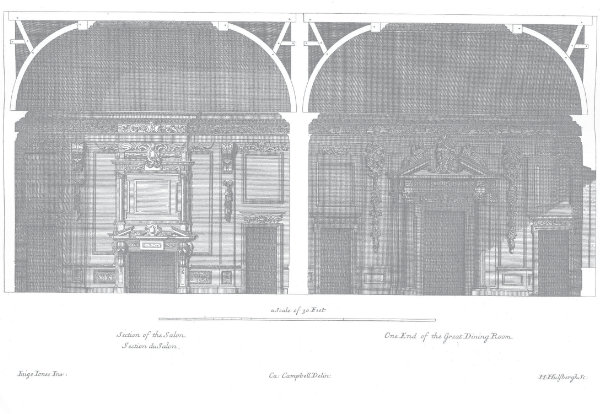

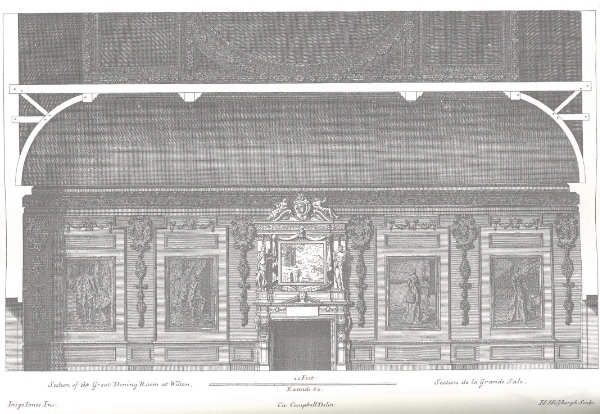

Personally, I do not think that musical and architectural proportions work the same way. For architectural proportions to be ‘harmonic’ they do not have to be exact. For example, if the double cube room at Wilton was not quite a double cube, is would not be any better or worse, it aims to be a cube and near enough is fine. Architectural proportion is like Goldilocks’s porridge, slightly too hot or cold is fine it is a matter of degree, the closer the better. Music is not like this, slightly wrong is the most discordant sound possible. If an octave is slightly off it sounds completely wrong, even the most tone-deaf person can hear when a violin is even slightly out of tune.

I am sure Palladio would have enjoyed someone post rationalising one for his buildings in terms of musical ratios, but I do not think he would have been at all familiar with these ideas and he certainly did not use them in practice. I can find no written reference to this Pythagorean musical analogy in his Quattro Libri. There may be some number ratios within his designs which appear to have a reference to these ideas but as D. Howard and M. Longair state in their essay ‘Harmonic Proportions and Palladio’s Quattro Libri’ ‘…this is more likely to be down to the practical advantages of using simple easily divisible numbers’. Which makes perfect sense particularly at a time when buildings were set out by lengths of rope and crudely pegged out on the ground.

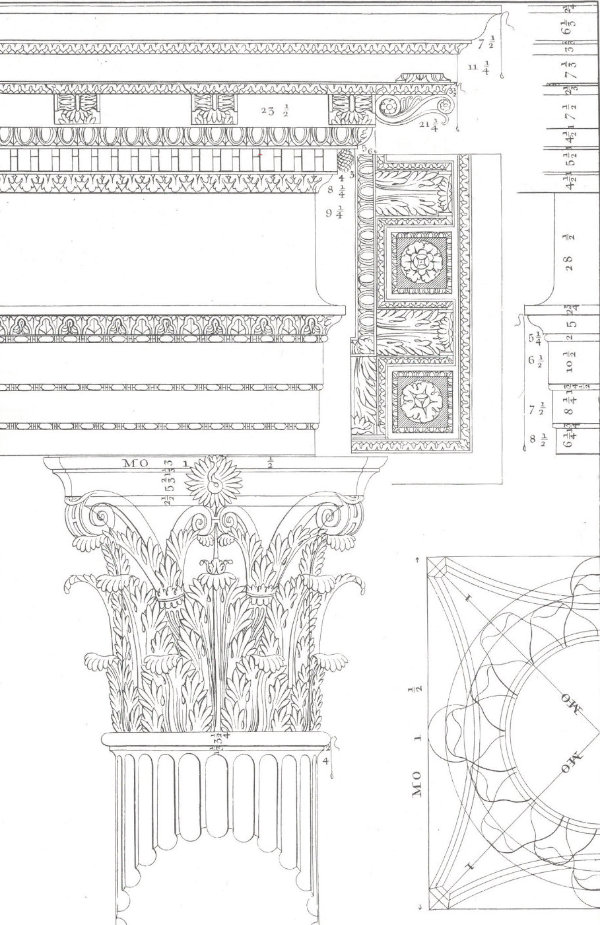

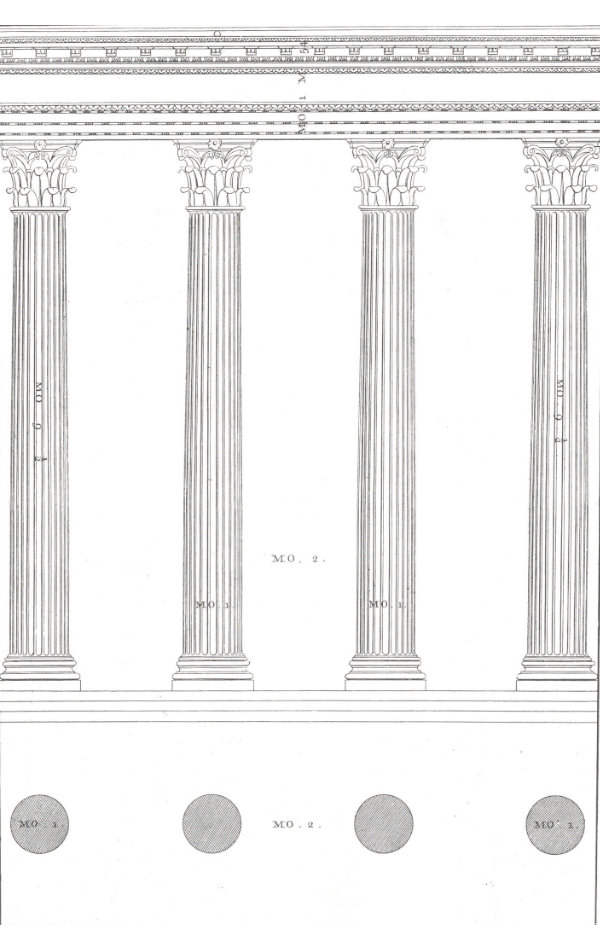

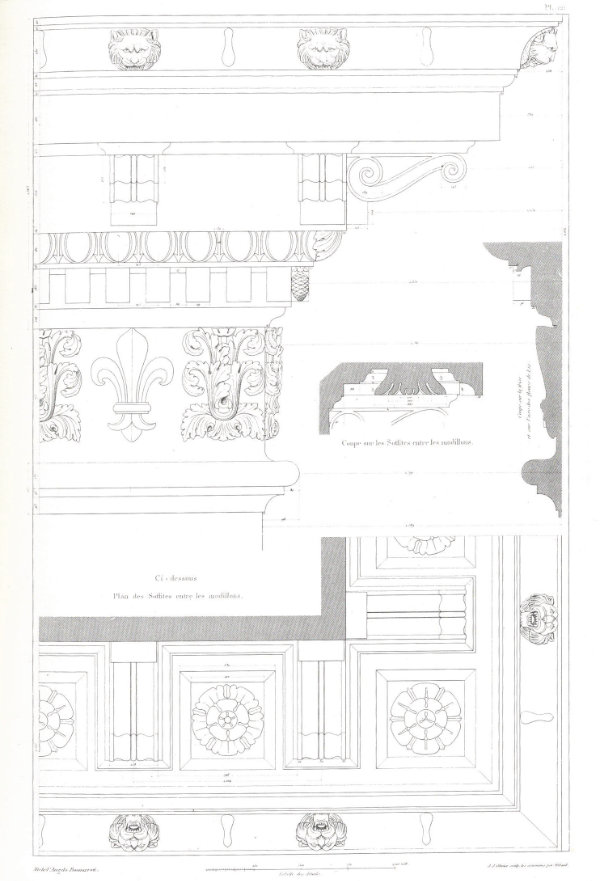

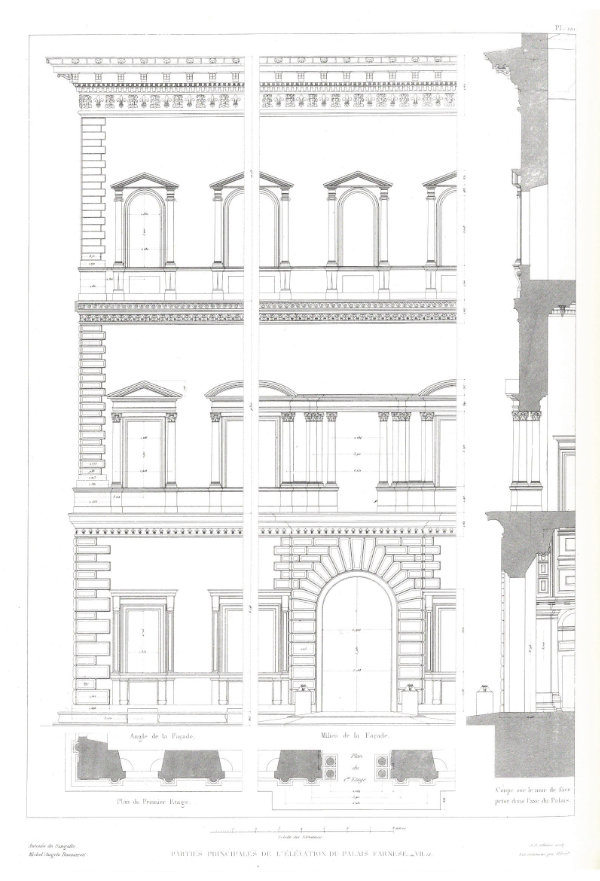

This certainly chimes with my understanding of Palladio’s architectural details. With his orders in the Quattro Libri, there is no attempt to use simple numbers let alone clean musical ratios. For example, the height of his Corinthian order is nine and a half times the length of the bottom diameter (rather that an even ten) and the entablature height is one diameter plus nine tenths (rather than an even two). The smaller scale details of the Corinthian order are just the same, virtually every dimension has a fraction attached and this is true for all his orders. Palladio’s drive was to represent a particular form or shape based on his knowledge of the ruins from Ancient Rome and his instinct for proportion. He therefore used whatever numbers and fractions worked to give him the exact dimensions.

If there is one set of proportions which I believe are inherently beautiful, these are the classical orders from Ancient Rome. Quite why these proportions are so beautiful is hard to fathom but what is clear is they have nothing to do with musical ratios. In John Summerson’s excellent essay ‘Antitheses of the Quattrocento’ he sums it up in the following way.

“If you are unwilling to accept the five orders as a gift of a myth, delightful and glorious fundamentally because they derive from an old, forgotten world, then you must argue yourself into believing that, somehow or other, they embody absolute values of proportion and ornament; and that argument is difficult in the extreme.”

If proportion cannot be attached to some absolute values all we are left with is personal judgement. There is a story about Michelangelo being criticised for making the cornice on Palazzo Farnese too large according to classical rules. To which he replied, ‘My eye is my measure’. Michelangelo, perhaps justifiable felt that his innate sense of proportion was enough with no recourse to anything else. He was effectively saying ‘I know what I like’, which does not sound like a valid architectural theory but perhaps that is all there is, and we should be honest about it.

In the office we spend hours analysing our designs and trying different proportions of windows and doors in slightly different places to ensure that we have designed the best possible building within the given constraints. It is worth taking time to get these things right because a well-proportioned building costs the same as a badly proportioned one yet is worth so much more. We do this primarily by intuition. This process is not academic or theoretical, but if some latter-day Alberti comes along and finds musical ratios in my work which ties into some greater cosmic order, I certainly will not complain but it does not make it true.