House in Ireland

As at Chiswick House where the patron, Lord Burlington, was also an architect, the client has been the driving force behind all architectural decisions for his new home. The practice of Quinlan and Francis Terry has gained a great deal from his eye for detail and thoroughness in all aspects of design. Also, they believe that the role played by their associates, Roger Barrell and Les Canham, cannot be overestimated. Likewise Declan Mullen, the clients representative, managed the project with great skill and enthusiasm.

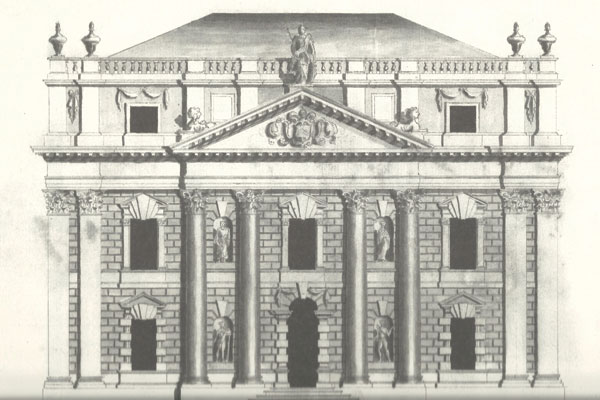

The story of this great house recreated by Quinlan and Francis Terry, combines grandeur with drama in what is perhaps a very Irish way. The great east entrance front of the house as built in c.1768-71 by Henry Prittie, the future 1st Baron Dunalley, provides the note of grandeur in this story for it seems to have been modelled on the royal palace of Greenwich, later Greenwich Hospital, as built for King Charles II in the 1660s. In England, unlike Ireland, it would have been inconceivable to have built a house in the Baroque language of a century earlier in the 1760s when the English, preoccupied with the latest fashions, were already captivated by the new neo-classical elegance of Robert Adam.

The note of drama in the story of this house came in the early twentieth century with the Irish Civil War when this emphatic expression of British rule and the monarchy was burnt in 1922. In order to receive compensation from the state for what could be defined as malicious damage, the 4th Lord Dunalley was required to rebuild the house and its service yards. This he did in 1925-7, though the top storey of the house was not replaced; the grand imperial staircase made way for a simple oak stair; and the interiors, formerly with rich plasterwork, were given oak panelling in an early Georgian style.

In the reduced economic circumstances following the Second World War, the 6th Lord Dunalley demolished the house in 1952, replacing it with what was effectively a bungalow, though retaining the rusticated basement and great flight of steps of the original house.

Designed as his principal work by William Leeson, a local landowner and gentleman architect, this house in Ireland had originally been built in the 1760s on an ambitious scale, five bays square, and four storeys high, including the substantial rusticated basement. The imposing east entrance front, eighty-four feet wide and seventy feet high was articulated with a giant order of four engaged Doric columns with a pediment over the central three bays, containing an oeil-de-boeuf window. The full Doric entablature with metope and triglyph frieze ran the whole length of this front and was supported at either end by coupled Doric pilasters or antae. The use of the stern Doric order, rather than the softer Ionic or Corinthian, gave the house an unusual gravitas.

The top storey above the cornice was a tall attic with a window over each end bay. The surrounds of the ground-floor windows had rustication with alternate blocking in the manner of James Gibbs who derived it from buildings such as the Palazzo Thiene in Vicenza by Giulio Romano and Palladio. This feature and the alternating triangular and segmental pediments over the windows were old fashioned touches for the 1760s. In templar form, the steps up to the entrance door ran the whole width of the three-bay columnar frontispiece. The confident grandeur of this house was provided by its huge scale, predominance of mass over void, giant order rising through two storeys, and pedimented Doric portico, while one of the features which made this façade special was the unusual height created by the provision of the full attic storey with windows, rising above the portico.

This façade, as we have noted, was very probably based on a building at Greenwich Palace, the river front of the King Charles Building which had been designed and built for Charles II in 1664-9 by John Webb, pupil of and successor to Inigo Jones. Leeson will have known this building from the engravings published by Colin Campbell in his iconic work, Vitruvius Britannicus (vol. I, 1715, pls 85-7). He may also have taken inspiration from a design for a house which was a virtual copy of the King Charles Building in ‘Miscellanea Structura Curiosa’, a manuscript volume of drawings prepared in 1745-6 by Samuel Chearnley (1717-c.1746).

John Webb’s masterpiece at Greenwich has been seen as the first Baroque building in England because of the unhesitating way in which it deployed large statements emphatically made, though the details and the giant order were derived from Palladio, notably his Palazzo Valmarana in Vicenza. It was also Palladio who placed an extra storey above the portico, as at the Villa Rotonda and the Villa Malcontenta (Foscari), and as followed at Greenwich and at this house in Ireland.

The client, having made several visits to country houses around Ireland with Quinlan and Francis Terry, became aware that this format of an imposing attic storey raised above the pediment seemed to be a particularly Irish development. They found it adopted not only at this house but at Bellamont Forest, Co. Cavan (1730), by Sir Edward Lovett Pearce; Russborough, Co. Wicklow (1748), by Richard Castle; and Castletown Cox, Co. Kilkenny (1767-71), by the Italian architect, Davis Ducart (Davis de Acourt), a house on the restoration of which Quinlan Terry had already worked in the 1990s for George Magan, now Lord Magan of Castletown.

One of the guiding features of the commission for rebuilding this house in Ireland given to Quinlan and Francis Terry in 2004 was that the client wanted this classical building to have an appropriately Irish flavour: hence, for example, the numerous visits which the three of them made together to other country houses in Ireland. In this context, it was also considered that the stone used should ideally come from Ireland, though much consideration was required as to the appropriate colours and combination of the stones. From an early stage, Terry recommended the combination he had seen at Castletown Cox which was grey Kilkenny marble for the architectural ornament and a buff coloured limestone for the ashlar walling.

Quinlan and Francis Terry regard themselves as fortunate to work with a brilliant mason, André Vrona, head of the firm of Ketton Stone, who had carried out the stonework for him at Ferne Park, Dorset. Vrona soon found that in Ireland there was a quarry still open at Ballinasloe which produced good grey limestone. However, finding it difficult to source a suitable buff coloured stone, he went all around Ireland and finally found a quarry owner in Donegal who was using his quarry to produce crushed road stone, from whom he managed to obtain large blocks of appropriately buff coloured limestone.

André Vrona erected about twenty large samples of stone on site in Ireland before the final decisions could be made. The enormously large Ballinasloe stones were then shipped over to Ketton in Northamptonshire where they were worked in Vrona’s workshop before being transported back from England to the site. The largest stones are the kneelers which form the bottom corners of pediments, the two on the entrance front weighing around twenty tons before being worked into their complex, partly triangular, shape. Huge cranes were required to lift them into position.

It should be stressed that everything at the house in Ireland is newly designed by Quinlan and Francis Terry except for the entrance front in which they recreated the original design of c.1768. The other three façades as well as the unique plan and all the interiors are new. The house in Ireland, as originally built, had been effectively a single façade house, for the north and south elevations were very plain with no entablature and were rendered in stucco, in contrast to the stone of the entrance front. Until its rebuilding in 1925-7, the ground floor had an impressive plan with a large entrance hall, 24 feet wide by 28 feet deep, leading to the rear hall where the magnificent staircase in the imperial form rose in a single flight, returning in two. Such a ceremonial sequence of hall and staircase was rare in the late 1760s but became fashionable towards the end of the century.

When they first met in 2004, the client showed Quinlan Terry views and photographs of the house as built by William Leeson of which all that remained was the greater part of the basement and the thirty-two foot wide flight of steps up to the front door. He wanted Terry to reconstruct a version of the main east elevation, but to improve the plain, stuccoed north and south fronts. The giant Doric columns and massive stones of the towering entrance front which Quinlan Terry rebuilt gave it a cyclopean scale and a strength, recalling the monumental language of Vanbrugh, Hawksmoor, or Ledoux. To emphasise mass rather than ornament, it was decided not to reinstate the coupled pilasters at the ends of the façade in the original house. The uncompromising masculinity is in harmony with the traditional origin of the Doric order which, according to Vitruvius, lay in the proportions of the male body.

Despite all this solidity, much surface delicacy is provided at this house in Ireland by the subtle horizontal and vertical tooling of elements of the stonework. Terry noticed that what was left of the stonework of the old building was not only rusticated up to the ground floor level, but also had a tooled finish which caught the light. When André Vrona produced samples of this tooling, the client decided that it should be applied to all the architectural elements except for the curved mouldings. The vertical tooling on the stones has to stop before meeting the edges where it could suffer damage, so that at this point there are narrow borders of horizontal tooling, creating a delicately alternating pattern which brings pleasure to the eye. In both texture and colour, all this tooling produces a lovely contrast with the smooth finish of the Ballinasloe limestone. It also creates near white highlights which provide an enlivening note, welcome on dark days.

A solution had to be found for the design of the five-bay west front, so it was decided that it should echo that of the new east entrance front but with the Doric columns replaced by pilasters, a simpler form reflecting the lesser role of the west front in the overall hierarchy of the house. This façade is an example of how the Terry office is increasingly looking to the George II style rather than to Palladio, for it echoes the five-bay entrance front of Frampton Court, Gloucestershire. In a rich mixture of Baroque and Palladian by an unknown architect in 1731-33, this is a favourite building of Francis Terry. Features which recur at the house in Ireland are the Gibbsian window surrounds with alternate blocking as well as segmental and triangular pediments; the urns along the parapet; the steps flanked by curved walls sweeping up to the central entrance; and the magnificent heraldic cartouche in the pediment like that designed by Francis for the pediment on the east front.

On the north front at the house in Ireland there had originally been a Venetian window in the centre of the first floor but it was agreed not to reinstate this because visual interest was to be provided more appropriately here by the addition of the rusticated Gibbsian surrounds to the windows which had not been carried out consistently either by Leeson or in the rebuilding of 1925-7. The similarly designed south front was improved by the addition of a large terrace which, approached from the drawing room, is well placed for outdoor use in the summer months. It leads down to the gardens from a twin armed staircase with, below it in the centre, a rusticated round-arched opening to the semi-basement or lower ground floor.

When work began on site at the house in Ireland in the autumn of 2007, it was necessarily on this semi-basement of which about half remained from the original house. Many of the spaces in this vast area were already stone-vaulted and since it was decided that the new interiors should follow this pattern, the building project was a major undertaking which lasted for a year before work could begin on the main house above.

Some of the new rooms are vaulted in rough stone but the central space was to be a more sophisticated octagon with a plain octagonal vault in smooth ashlar. At a meeting on site in 2008, the client asked Quinlan Terry if the horizontal arches of these vaults could be arched. The answer was that they could be if he were prepared to echo the ambitious model of centralised vaulted spaces such as the Water Court Vestibule at Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli (AD 117-38). An inventive architect himself, Hadrian once criticised a work by Trajan’s architect, Apollodorus of Damascus, who supposedly replied rashly, ‘be off, and draw your pumpkins’, a reference to the design of the complex umbrella vaults at Tivoli which was sometimes attributed to Hadrian.

After Terry had shown the client illustrations of interiors of this kind at Tivoli, he agreed to adopt this form which, incidentally, had already inspired Baroque interiors such as that of Borromini’s hexagonal church of Sant’Ivo della Sapienza, Rome (1642-72). The construction of an arched octagonal vault such as that at this house requires not only stone ribs rising to a central circular ring, but eight of the complicated stones known as ‘tas-de-charges’ which support the ribs where they spring out from the wall.

Though these are the key element of all Gothic vaulting in England and the continent, the term to describe them is French because the masonry yards of the medieval cathedrals in France were not closed down in the sixteenth century as they were in England. As a result, the art of cutting and dressing stone, properly known as stereotomy, survived without a break in France where complex stone vaults played a major role in classical buildings throughout the post-medieval period. The segmental head of the open arches at the house in Ireland reflected the form found in earlier outbuildings at the house.

Once again, it was André Vrona’s understanding of stonework and vaulting that enabled this complicated work to proceed without any problems. Terry doubts whether anyone else in this country would have been able to execute it so expeditiously and with so much enthusiasm. The octagon is surrounded by a variety of passages and vaulted interiors opening dramatically into each other in a way that recalls the contrasts of light and shadow in the powerful engravings of Roman buildings and ruins by Piranesi.

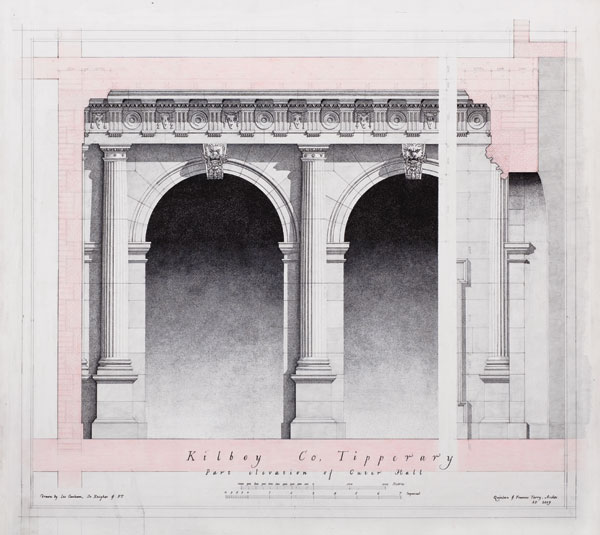

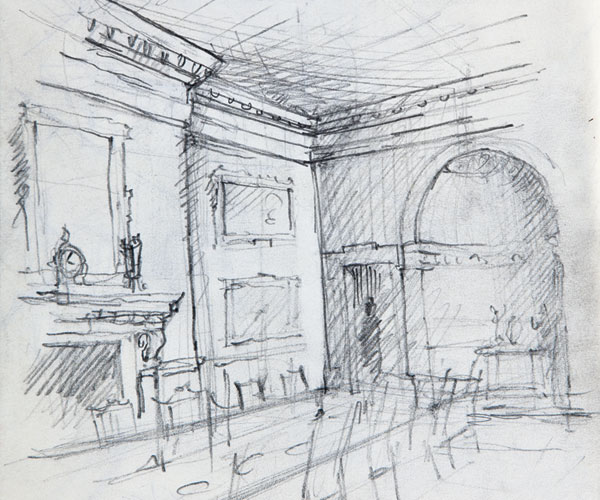

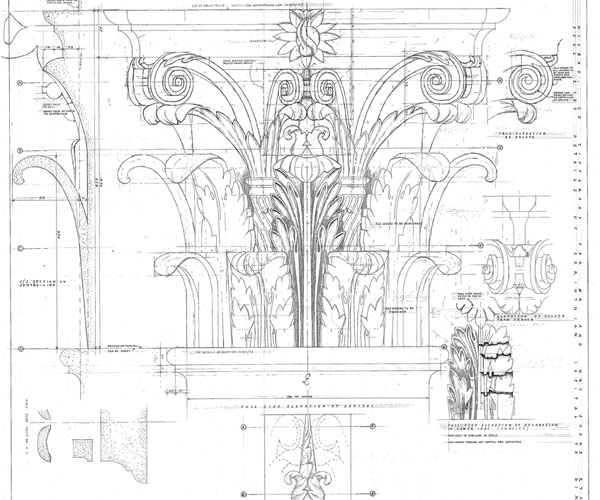

Having climbed the great flight of steps up to the entrance front, the visitor is rewarded by finding an entrance hall of matching grandeur. It has as one source of inspiration the Stone Hall at Houghton Hall, Norfolk (1722-35), by Colin Campbell, James Gibbs, and William Kent, which had impressed the client on a visit. Terry worked up a design for the outer hall at the house in Ireland with a Gibbsian Doric order, ultimately derived from Vignola, complete with fluted columns on pedestals, egg and tongue enrichments in the capitals and cornice, rosettes in the necking bands, bucrania in the metopes, mutules in the cornice, and lion heads in the centre of the arches. Another source for this rich order is the Porticus of Gaius and Lucius Caesar at the Basilica Aemilia in the Roman Forum which had a giant Doric order with rosettes in the metopes and in the necking bands of the columns. This lavish monument, demolished in c.1500, was paid for by Augustus in 2BC and further enriched with marble columns twenty-four years later when it was hailed by Pliny the Elder as one of the three ‘most beautiful buildings the world has ever seen.’

At the house in Ireland, the undersides of the mutules placed over each triglyph in the frieze below the soffit of the cornice are packed with carved oak leaves and acorns as at the Basilica Aemilia. They are clearly shown in a drawing of the building by Palladio which was a key element for Francis Terry in his design for the outer hall. The bucrania or ox skulls with sacrificial garlands placed in alternate metopes in the triglyph frieze are derived from the study by Francis of as many as six sources, all differing in detail from each other: those at the Basilica Aemilia; in Vignola’s Canon of the Five Orders of Architecture (1562); and in Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture (1570) as well as in his Basilica and Palazzo Chiericati in Vicenza and Convento della Carità, now part of the Accademia, in Venice.

The keystones of the three, round-headed arches on the west wall take the form of massive lion heads which support the entablature. With flowing manes and mouths grasping garlands of Irish flowers which they are presumably eating, these exuberant heads were designed by Francis Terry and carved from a clay model by Tim Lees in his Somerset workshop. They owe something to the lion heads in the hall at Castletown, Co. Kildare, begun in 1722 as the first great Palladian mansion in Ireland from designs by the Florentine architect, Alessandro Galilei, under the direction of Sir Edward Lovett Pearce. While working on the designs for the house in Ireland, the Terrys and the client visited Castletown, not to be confused with Castletown Cox, Co. Kilkenny, which, as we have seen, they also visited.

Entrance halls in houses on the scale of the house in Ireland are traditionally seen as semi-external public spaces, transitional between the exterior and the domestic character of the private rooms. Thus, the walls of the entrance hall are lined with unadorned Portland stone, drawn by Francis Terry and executed by André Vrona’s masons. This plainness provides a visually stimulating contrast with the closely packed carved ornament which, as we have seen, dominates the entablature of the Doric order. The simplicity of the walls is broken on the north and south sides of the room by chimneypieces with swan-necked pediments and friezes rich with fruit, red squirrels, and sprays of leaves, all of which can be found at the house in Ireland. These were exquisitely carved by Tim Lees and Andrew Tanser from designs by Francis Terry who had been influenced in their general design by chimneypieces in other Irish country houses.

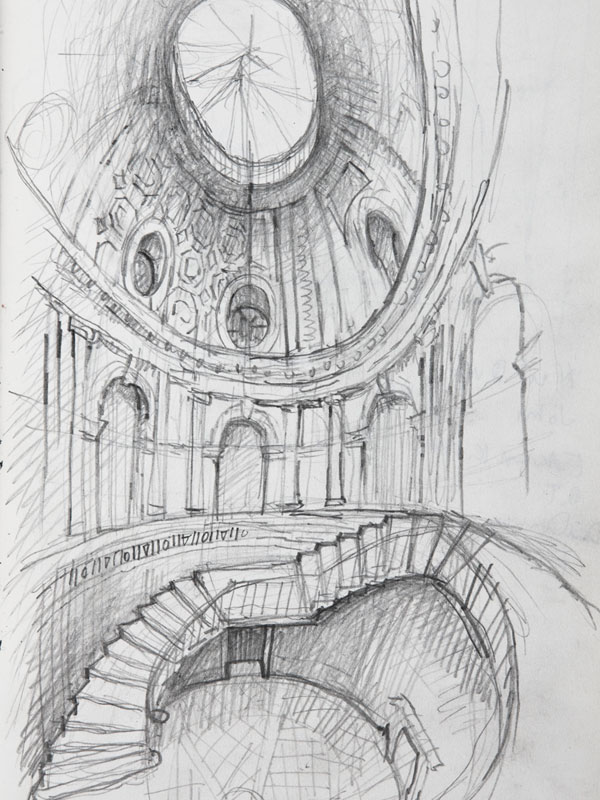

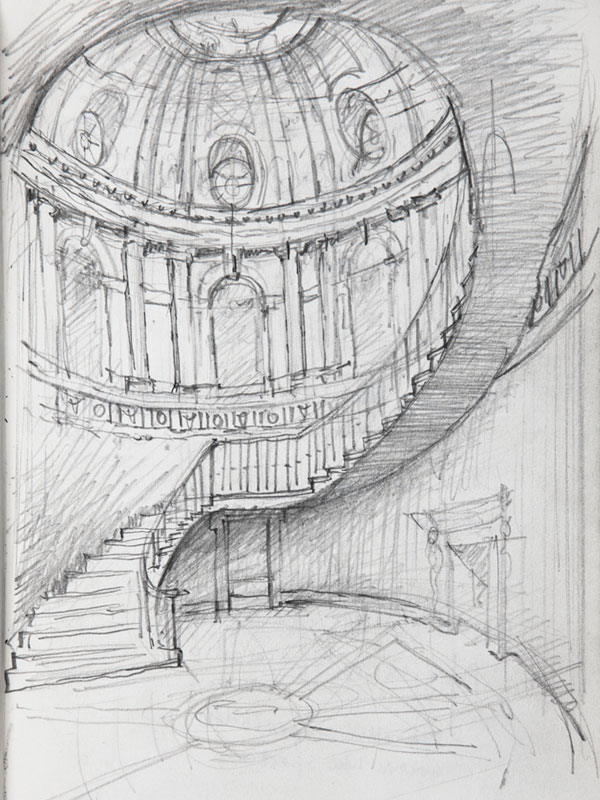

The entrance hall opens dramatically through the three archways into the staircase hall, a breathtaking elliptical space, 27 feet 6 inches by 37 feet, and 51 feet 7 inches to the top of the lantern. At least nine different designs were sketched by Francis Terry during 2009 for the treatment of both the walls and the dome, two for the latter incorporating oval lunettes. As built, it is surrounded at first-floor level by a series of six segmentally-headed open arches separated by Ionic pilasters of grey-green scagliola, influenced by those the client admired at Castle Coole, Co, Fermanagh, by James Wyatt of 1790-97.

Above the open arches rises a large ellipsoidal dome with octagonal coffers, each with a central rosette, surmounted by a glazed elliptical lantern. Together with the client, the Terrys went to see Townley Hall, Drogheda, Co. Louth, by Francis Johnston, of 1794, which has a stunning staircase hall with a circular dome and a central staircase. This was to be a great influence on the house in Ireland, though the shallow steps of its cantilevered staircase were made an inch wider than those at Townley Hall at the client’s request. They are easy to ascend but the considerable time it takes one to reach the first floor is a forceful reminder of the large scale of this house. The steps, as at Townley, have a smooth soffit, not the stepped soffit associated with a slightly later date.

The great oval staircase at the house in Ireland ascends only to the first floor, though Quinlan Terry’s original proposal was for it to go up to all floors. Francis became worried about this because he had noticed that almost all grand Georgian staircases go up only one flight, so the dome in the first scheme would be three floors up rather than two, making it rather too high for its width. Also, the summit of the stairs, with its beautifully clear view of the dome, would be less visited as it would not be on the piano nobile.

The client and Francis Terry visited Northwick Park, Gloucestershire, to see the circular staircase of 1828-30 with a glazed lantern over the dome, possibly designed by the 2nd Lord Northwick. The dome is not decorated with coffering but with lotus leaves arranged like fish scales, inspired by the laurel leaf ornament of the roof of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens. The client was considering this ornament for the dome at the house in Ireland, and though this idea was rejected, he and Francis noted that the dome at Northwick lacked impact by being at the top of the house over the second floor.

The banisters on the staircase at the house in Ireland and the railings in the arched openings are of brass, a material introduced as an Irish touch because it features on staircases at other country houses in Ireland such as Castletown and Townley. Since the Castletown example was thought to be too massive for such a delicate staircase, a Palladian version of the thinner Townley banisters was adopted. On the first floor a generous ambulatory or access corridor runs round the outside of the staircase hall of which it commands views through the five arched openings.

Quinlan and Francis Terry had designed many coffered domes but that at the house in Ireland was the first to be executed. Elliptical domes have long interested Quinlan Terry as they formed a substantial part of his Sir Herbert Baker Scholarship of 1974 from the Royal Academy to study unreinforced dome construction in Persian and Roman buildings. Francis had himself long been inspired by the elliptical glazed dome in the Marble Saloon of 1775-88 at his school, Stowe, Buckinghamshire.

The decision to make the dome at the house in Ireland elliptical, in contrast to the circular one at Townley, was a major challenge which the Terrys were happy to take on because the rare choice of an ellipse brings a magical lightness to such an interior which would more normally be circular or square. Elliptical plans suggest movement through space in contrast to the more static character of the centrally planned, circular interior. First introduced in churches in Rome by Vignola between 1550 and 1572, elliptical domes and plans were to become a hall mark of the Baroque in the seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries when their potential for dynamic movement was fully exploited.

The most notable examples of the Baroque obsession with elliptical domes are S. Andrea al Quirinale, by Bernini, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, by Borromini, and San Giacomo in Augusto in the Corso, by Maderno, all in Rome; and in or near Turin, the Palazzo Carignano, by Guarino Guarini, Stupinigi, by Filippo Juvarra, and the great ducal sanctuary of the Madonna di Vicoforte at Mondovi which was one of the most helpful to the Terrys. Begun as early 1596 from designs by Ascanio Vittozzi in a remarkable anticipation of Juvarra and Vittone, the leading late Baroque architects of Piedmont, the Vicoforte dome is 119 feet long by 80 feet wide, and thus probably the largest of its shape. A technical feat of the utmost daring, it was not executed till 1728-33. It is penetrated by oval lunettes which, as we have noted, also featured in some early designs for the dome at the house in Ireland but were finally omitted.

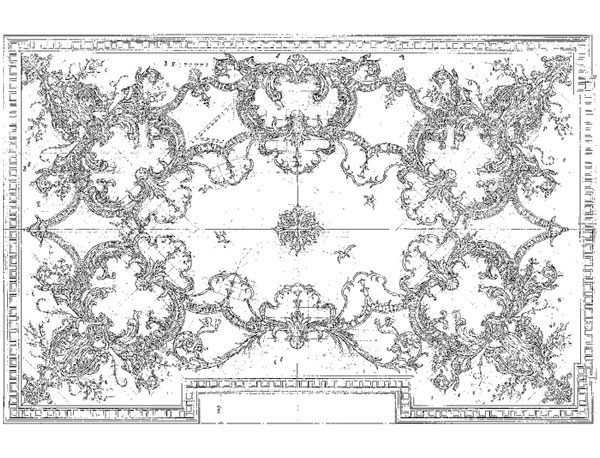

The fascinating aspect of elliptical masonry dome construction is that it cannot be reinforced with chains because under pressure an ellipse will become a circle, so that all masonry elliptical domes are massive in their construction. Drawing out the house in Ireland’s dome was a virtually impossible task as every line is part of a three-dimensional curve. The shape was determined partly by drawing but also by a 1/10 model made by Locker and Riley, specialists in the manufacture of fibrous plaster.

A further challenge concerns the setting out of the coffers in an elliptical dome because whereas those on a half sphere are all regular, those on a half ellipse are inevitably irregular between the axes, though they are regular on the major and minor axes. Francis Terry observes that it is interesting to see the ways in which Borromini and Bernini get round this problem at San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane and S. Andrea al Quirinale, and that one can also see another example at Stowe. The irregularities are clearly noticeable but do not worry the viewer for, if carefully handled, the eye accepts them. The working drawings for the dome were made by Eric Cartwright in the practice of Quinlan and Francis Terry. His skills in complex geometry had already been developed at Bury St Edmunds Cathedral for which he had made ninety percent of the working drawings for the new tower.

There remained the further question of what shape and size the individual coffers on the ellipse at the house should be. In the end, it was agreed that the most appropriate arrangement would be just three tiers of twenty-four coffers of diminishing size as they rise. A plaster model was then made to see how to handle the distortion as one moves from the major to minor axis on an ellipsoid. It is important to realise that a circular dome has an enormous amount of repetition and therefore the three coffers can be repeated twenty-four times, whereas an elliptical dome has only two repeats.

The shape of the coffer would customarily be either a diamond, octagon, or hexagon. For example, in the staircase hall at Townley, which is circular, the dome below the lantern has diamond-shaped coffering. This is easier both to design and to construct than octagonal coffering in an ellipse as at the house in Ireland. Francis Terry studied Robert Adam’s octagonally coffered circular saloon at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire (c.1760-70) which was probably inspired by the superbly worked out octagonal coffering in the central octagonal saloon of Lord Burlington’s Chiswick House, Middlesex (c.1725-29). It was the coffering at Kedleston and the examples in Gibbs’s Book of Architecture that provided the principal models for that at the house in Ireland, once it was decided that it should be octagonal.

Since the staircase hall at the house in Ireland is directly over the vaulted octagonal hall in the semi-basement, the reflection of this shape in the coffering is a kind of visual pun which appeals to the client. There is precedent for it in Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane where the shapes of the coffers in the dome, variously octagonal, hexagonal, and cruciform, have sometimes been seen as reflecting possible ways of interpreting the complex plan of the church.

The plan devised by Quinlan and Francis Terry for this house is compact and with the exception of the breathtaking staircase hall at its core, in general follows the simple and practical pattern found in Palladio which is sometimes called the noughts and crosses plan. The outer entrance hall in the east front is flanked on the north side by the library and on the south by the client’s study which leads into the drawing room and then through to a second study. These three rooms with all their doors in axis fill the south front on the ground floor, while on the north front the library opens into the longer dining room through a screen of two Corinthian columns of specially made Brocatelle Siena scagliola. The library is lined with superb bookcases designed by Francis Terry with pediments supported on fluted Corinthian pilasters which have the complex capitals. The bookcases also owe something to William Kent’s exquisite, pedimented tabernacles of 1724-5 in the entrance hall at Ditchley House, Oxfordshire.

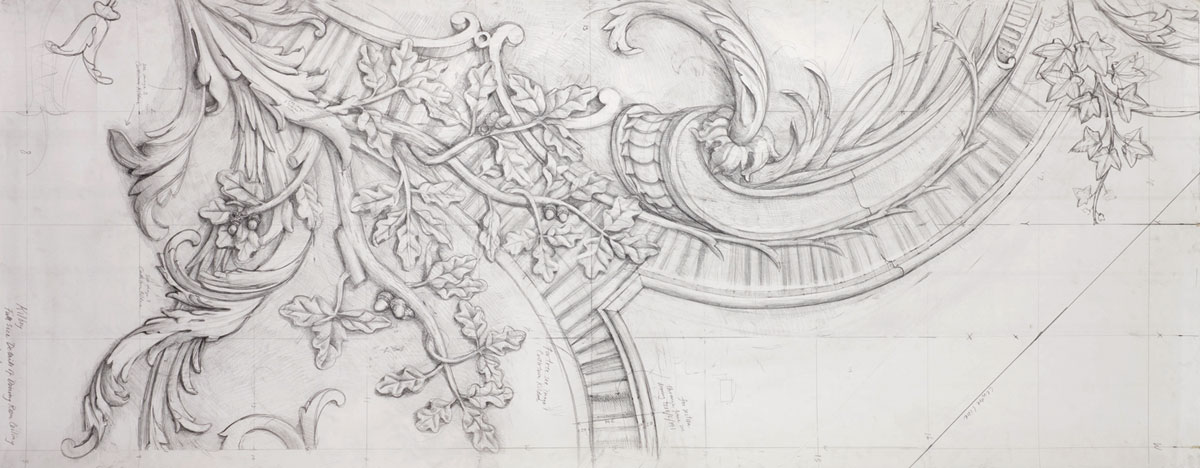

The principal rooms on the ground floor at the house in Ireland have breathtaking plasterwork designed by Francis Terry from August 2010 on the basis of that in Castletown and houses in Dublin by the two Francini brothers, Paolo (1695-1770) and Filippo (1702-79). They came to Ireland in c.1730 via Germany from Tricino, the area of Italian-speaking Switzerland which had at that time produced many stuccadores and architects including James Gibbs’s master, Carlo Fontana. Francis and the client visited many examples of Francini work in Ireland and also went to Bavaria and Potsdam with the plasterer to see and sketch the kind of Baroque and Rococo work which had inspired the Francini brothers. Francis also visited Castletown with the plasterers from Locker and Riley who sent a modeller there to copy the Francini style. The white, swirling plasterwork of the ceilings at the house in Ireland, incorporating exotic ho-ho birds, shells, and succulent plant forms, has not been equalled in richness and quality since the eighteenth century. Francis discovered the infinite adaptability of Rococo to objects of vastly different scale and character from jewels, china, and chairs, to massive ceilings.

Especially memorable is the lush plasterwork of the ceiling in the drawing room which was carried out in a great hurry because Francis Terry rejected the first attempt by Locker and Riley who thus had to do it again, necessarily very rapidly in order to keep to the programme. Francis believes this was a happy accident because the Francini borthers, working in stucco rather than fibrous plaster, must themselves have worked with incredible speed. This gives the ceiling a spontaneity and life that more laboured work would lack. A scene showing ho-ho-birds, the mythical birds of East Asia who reigned over all other birds, fighting over an eel and a trout, was added to relate to the lake at the house in Ireland.

The plasterwork in the dining room shows up especially well against the polished Pompeiian red walls and also relates to the generous white Corinthian capitals of the Siena marble scagliola columns. Francis Terry explains that ‘You cannot cast a Corinthian capital from only one mould’, so that all elements of these capitals were moulded and applied individually to give a lightness which most modern cast capitals lack. He agrees with Vincenzo Scamozzi who claimed in his great work, The Idea of a Universal Architecture (1615), that ‘Among all the five orders, there is really none more distinguished or beautiful than the Corinthian and so it is more than right that it surmounts all the others. Its elegant pedestals, the graceful fluting of its columns, its beautiful capitals with olive leaves and vines, its particularly harmonious composition and the parts of its cornice with scroll shaped modillions and carvings dotted here and there, resemble the graceful bearing and innocent beauty of young virgins.’

In the ground floor rooms the doors are polished Cuban mahogany which had been stored for 40 years by a small furniture maker, Fitzgerald in Cahir, who manufactured them. They have fielded panels arranged in an Irish pattern with long horizontal panels at the top and bottom. The doors in the first floor corridor are curved polished mahogany with fielded panels. The remaining first and second floor doors throughout the house are painted wood.

Taken from The Practice Of Classical Architecture by Professor David Watkin, Published by Rizolli, 2015