House in Regent's Park, London

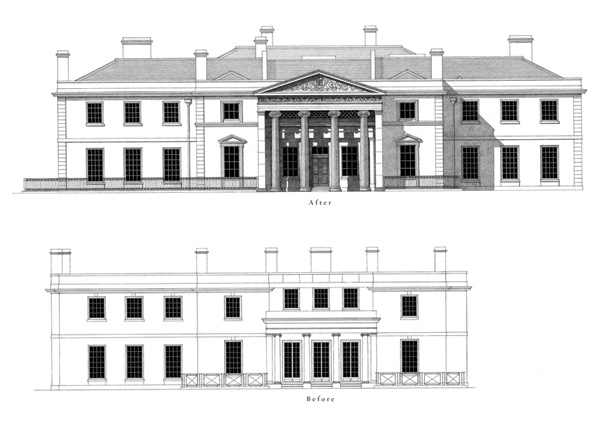

This magnificent new mansion, built in 2003-10 from designs by Quinlan and Francis Terry, began as a simple classical villa built by Decimus Burton in 1827 as part of John Nash’s plans for his Picturesque layout of Regent’s Park. In 1910 it was enlarged by Edwin Lutyens whose alterations included the addition of a wing on the left-hand side, making the whole composition asymmetrical, a surprisingly clumsy touch for an architect of such genius. It was subsequently taken over by the University of London for use as a hall of residence when unsightly new buildings were added in the grounds. When the University left in 1995, these were demolished and the Crown Estate decided to sell a long lease to be used, once more, as a private dwelling. This continued their programme of commissioning six new villas to be built on land running north-east of this property. Quinlan Terry had been appointed architect and the first of his villas to be built, Ionic Villa (1988-90), was bought by the client who was soon to also acquire Hanover Lodge next door which he commissioned Quinlan Terry to restore, improve, and enlarge.

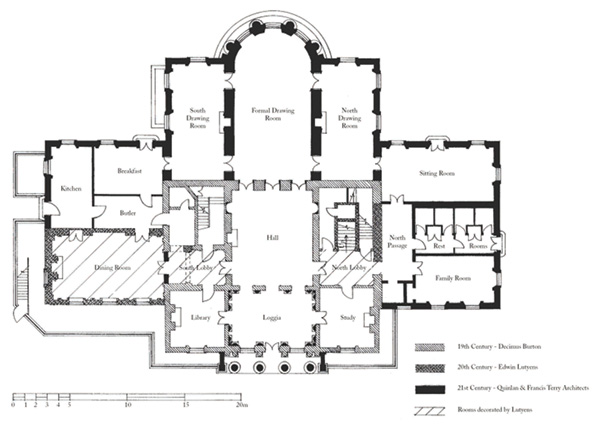

English Heritage insisted on the retention of some elements of both the villa by Burton and of Lutyens’ alterations to it, and the skilful response of Quinlan and Francis Terry to this challenging requirement as well as creating a house of far larger size is seen in the plan. This includes the dates of the various parts and also shows the three dramatic axial vistas which the Terrys made through the house, one running from south to north, and two from west to east.

Their designs went through many major changes including the addition of a wing on the north-east side to balance that by Lutyens on the south-west. This made the one-storeyed, un-pedimented entrance portico by Decimus Burton inadequate for a house on this scale, so Francis Terry cleverly incorporated it within their much larger portico. All this involved many discussions with English Heritage, Westminster City Council, and the Georgian Group who objected to the increasing size of the new house, but planning consent was finally granted late in 2005.

An almost theatrical touch is given to the approach to the house in Regents Park by the pair of entrance lodges which flank it. Francis Terry originally prepared designs in the Ionic order for these which he provided with octagonal roofs, while his father made an alternative design in the Greek Doric order and on a square plan. The two schemes were presented in a format using computer models so as to show the effect that both would create as one moves along the Outer Circle which surrounds Regent’s Park and turns into the drive. The patron eventually selected the Doric order which is appropriate for the traditional role of a lodge as a guard house because Doric supposedly originated as a representation of the masculine strength of warriors and heroes.

The lodges, built in reconstructed stone, feature pedimented porticoes with pairs of fluted, baseless Greek Doric columns and a full triglyph and metope frieze, modelled on the Doric order of the Parthenon. Linked by fine ironwork gates and railings punctuated with elegant lamps, these striking lodges can be paralleled, like the entrance front of the house itself, in the work of Schinkel, as in his now demolished twin Greek Doric templar lodges of 1823 at the Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. However, unlike these German examples, the entrance lodges at the house in Regents Park boast porticoes which unusually appear on all four sides. This creates a complex rhythm at the corners which assume a re-entrant character where the antae, of stuccoed brick, meet each other at right angles.

Since the lodges are placed on the angle of the Outer Circle as it turns right, the left-hand lodge is concealed as one approaches the house in Regents Park up the Outer Circle from which the right-hand lodge serves as an elegant, centrally-placed terminus to the vista like an ornamental building in a landscaped park. To discover as one approaches, that it is one of a pair, is a coup de théâtre in conformity with eighteenth century Picturesque theory which stressed the importance of surprise.

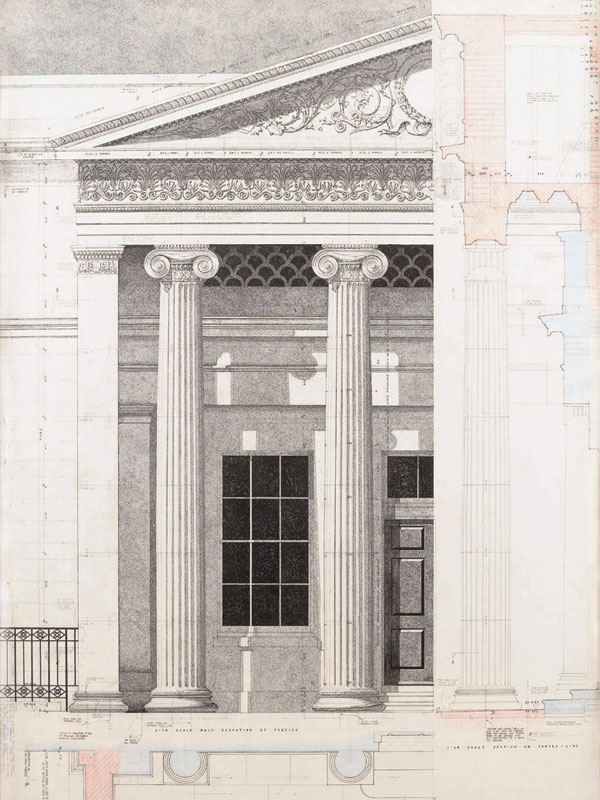

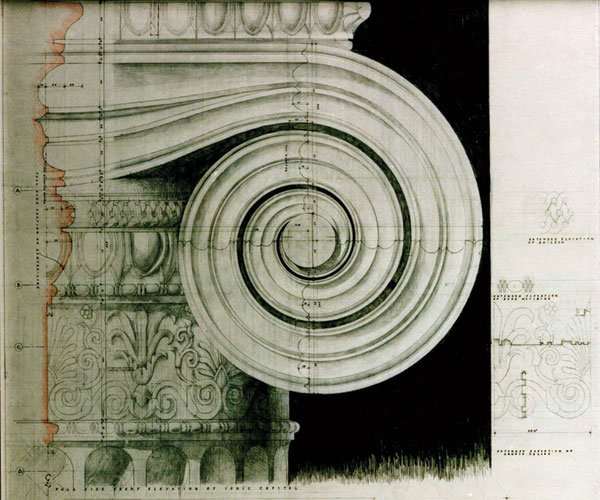

The entrance front of the house in Regents Park is dominated by a full height portico with free-standing columns in antis in the Greek Ionic order of the porticoes at the Erechtheion, built in 469-429 BC on the Acropolis in Athens. This gives it a neo-classical flavour recalling Karl Friedrich Schinkel whose portico at his Schauspielhaus (theatre) and colonnade at his Altes Museum, of 1818-23, in Berlin, are also both in the Erechtheion Ionic order. This order was also adopted for the columns on the curved bow of the centrally placed principal Drawing Room on the garden front of the house in Regents Park.

Below the volutes of the Ionic capitals at the Erechtheion the shaft of the columns are decorated with a band or necking carved with a stylised anthemion, that is honeysuckle, pattern, so that this order is the loveliest and richest of all Greek orders. Since the porticoes at the Erechtheion are of different sizes, the columns are of three different heights: 5.5, 6.5, and 7.15 metres. The same is true at the house in Regents Park where the columns of the bow on the garden front are 7.6 metres high, and those on the entrance portico, 6.3 metres, virtually the same as those on the north portico of the Erechtheion. In a neat piece of geometry, the top diameter of the columns on the bow is the same as the bottom diameter (660 mm - 2 ft 2 inches) of those on the entrance portico. Both the Erechtheion and the house in Regents Park are unusual for using the same order at different scales.

Francis Terry boldly applied the anthemion pattern of the cyma recta over the door in the north portico to the frieze of the portico in the kind of inventive touch which could, of course, be found in antique architecture itself: for example, at the Hellenistic Temple of Apollo at Didyma near Miletus in what is now Turkey, the anthemion band adopted by Terry had been transferred to a massive circular plinth which surprisingly replaced the upper torus moulding on some of the column bases.

The first revival of the Erechtheion Ionic order seems to have been that in the circular Temple of Roma and Augustus built on the Acropolis in Athens by the Emperor Augustus. It was then not revived until the archaeologist and architect, James ‘Athenian’ Stuart (1713-88), used it for the façade of Lichfield House, 15, St James’s Square, London, in 1763.

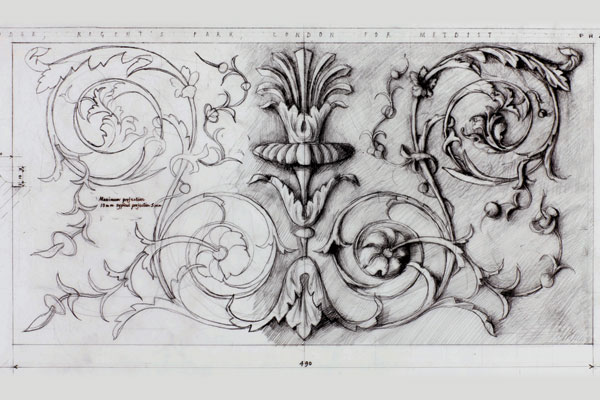

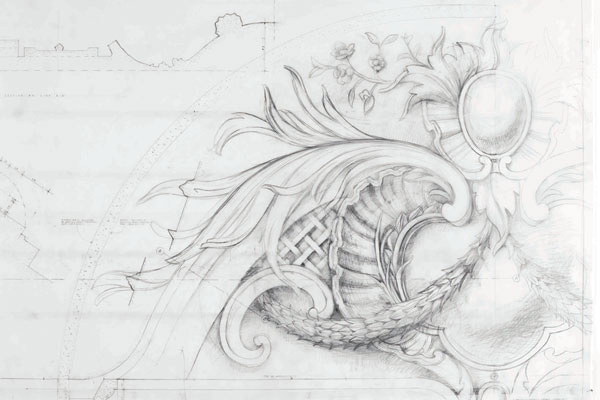

For the tympanum of the crowning pediment, Francis Terry designed a rich scheme of decorative plasterwork with acanthus leaves and shoots swirling round a central circular panel. This lively pattern of rinceaux is characteristic of one of the greatest monuments of Augustan classicism, the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace) in Rome. Carved by Greek workmen, this was built in 13-9 BC by Augustus who was an admirer of classical Greece and of the golden age of fifth century Athens. It has been a rich source for Francis who has studied it carefully, making his first drawings of it in Rome in June 1988 for the enhancement of the three interlocking State Rooms in 10 Downing Street, a commission which the practice had received from the Prime Minister, Mrs Thatcher.

Dating from the 1730s and almost certainly designed by William Kent, these interiors have fine chimneypieces in carved marble but the original decorative overmantels, overdoors, panelling and ceilings had been removed. The carved panels of the Ara Pacis Augustae, famous for the naturalism of their rich yet delicate scrollwork, were the ideal source for filigree panels over the four small doors in the Pillared Room which, before they were added, were too low for a room of this size. In the Terracotta Room and White Room the Terrys added richly carved overdoors, new decorative ceilings enriched with ornamental plasterwork incorporating the national flowers, rose, shamrock, daffodil, and thistle, as well as a Doric overmantle with the Royal Coat of Arms in the Terracotta Room and a Corinthian overmantle with spiralling fluted columns and swanneck pediment in the White Room. All this was valuable preparation for the elaborate plasterwork in the interiors at the house in Regents Park which we shall now explore.

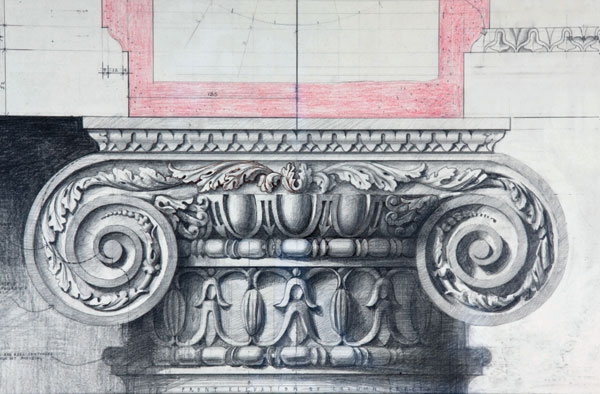

The entrance hall to a classical house is seen as a transition between exterior and interior so that its walls are traditionally stone-coloured to give a somewhat external character. That pattern is followed in the Entrance Loggia at where the stuccoed walls were given a finish simulating Portland stone. The room incorporates an ancient Roman Ionic order based on an ornate capital with an egg and dart as well as bead and reel mouldings over a large necking band of plant buds. Reused in the twelfth century in the nave of Sta Maria in Trastevere in Rome, this had been found by Francis in an engraving in Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Della Magnificenza ed Architettura de’Romani (1761). His aim in this polemical book had been to re-affirm the inventiveness of Roman architecture in the face of claims for the superiority of Greek architecture by Julien-David Leroy in Les ruines des plus monuments de la Grèce (1758), the first ever publication of measured drawings of ancient Greek architecture.

In the bases of these Ionic columns in the Entrance Loggia, which rest on pedestals, the torus moulding is enriched with guilloche ornament, but the lower torus moulding is omitted, as recommended by Vitruvius and illustrated by Palladio in I Quattro Libri (1570), though surprisingly this form was not adopted by the Palladian architects of eighteenth century England or by those of Renaissance Italy with the interesting exception of Michele Sanmicheli (c.1487-1559) in his palaces in Verona. Francis Terry is an expert on the important but little studied subject of base mouldings on which he wrote his dissertation as an undergraduate reading Architecture at Cambridge.

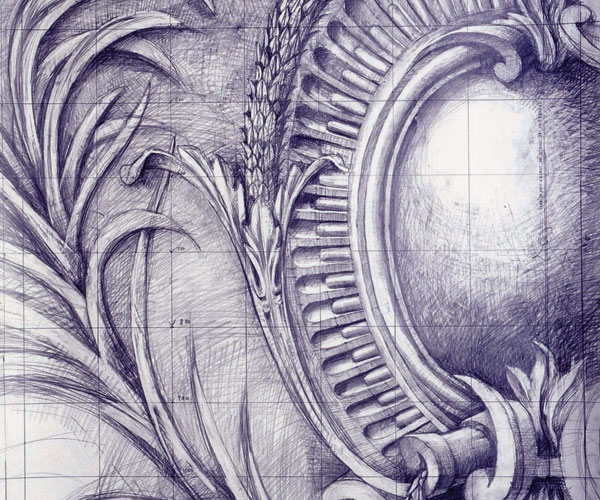

In the entablature in the Entrance Loggia which is complete with architrave, frieze, and modillions, the rich frieze featuring pairs of succulent cornucopia between anthemia, echoes an ancient one, also recorded by Piranesi in Della Magnificenza ed Architettura de’Romani where he recorded it as surviving in the grounds of the Villa Mattei in Rome. Thus, with the Piranesian source of the Ionic capitals in this room, Francis Terry thinks of the Entrance Loggias ‘the Piranesi room.’ There are indeed rich resonances here which link ancient Rome with the twelfth, eighteenth, and, twenty-first centuries. This work, together with the ceiling, was carried out in fibrous plaster made at the firm of Clark and Fenn by the carver, Geoffrey Preston.

The marble floor in the Entrance Loggia is influenced by that designed by Palladio for the monks’ choir in his church of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice (1566-89), which has a complex and ingenious pattern of lozenges in marbles of vividly contrasting colours, Brocatello Siena, White Statuary, Black Belgian, Red Verona, and Green Verde Antico. In view of its extreme rarity, the Brocatello Siena marble in the house in Regents Park floor with its exceptionally deep golden colour took three to four years to source.

Quinlan Terry, who had made a drawing of the floor in San Giorgio Maggiore, on a visit in August 1974, is unusual among current architects for the trouble he takes with what we might call floorscape, whether in parquet or marble. For example, he used the San Giorgio Maggiore floor pattern in the loggia of his Villa Veneto next door to the Ionic Villa where at the client’s request, he added polychromatic marble floors in geometric patterns to replace the simpler floors in the house as first built. Such floors are, of course, part of a revival of an ancient Roman practice, though guide books to Venice rarely if ever mention the fine floors which play such a vital visual role in churches such as San Salvatore, Sta Maria del Giglio, and even in Palladio’s celebrated San Giorgio Maggiore, all of which have been a source of inspiration to Quinlan and Francis Terry at the house in Regents Park.

Just as the work by Lutyens in the former Entrance Loggia, had been removed in the 1930s, so it was from the two rooms flanking it. In remodelling these as a Library and Study, the Terrys added impressive new chimneypieces in each of them in White Statuary and Brocatello Siena marble. Carved by Timothy Lees to designs by Francis Terry who took inspiration from some by Robert Adam at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire, they feature a frieze of a rich Brocatello Siena marble against which is silhouetted floral ornament in white marble, drawing on honeysuckle and other plants. These chimneypieces are like small pieces of architecture and each took about four to six months to carve. Marble floors were also laid down in the Study and Library in Belgian Black, White Statuary, and Brocatello Siena, inspired by the floor pattern in Sta Maria del Giglio (Zobenigo), Venice, a rich Baroque masterpiece of the 1680s by Giuseppe Sardi.

Approached axially from the Entrance Loggia, the Hall is the central space of the house with a balustraded gallery at first-floor level and above this a cove with an elliptical oculus. This double height space was not on Quinlan Terry’s original drawing but Francis Terry who has a taste for such spaces added it during the working drawing phase. The room takes its inspiration from three double-height halls: that by Inigo Jones from 1616 at the Queen’s House, Greenwich; Moor Park, Hertfordshire (c.1720-8), by Sir James Thornhill; and the Stone Hall at Houghton Hall, Norfolk, by Campbell, Gibbs, and Kent, begun in 1722. All three are forty-foot cubes, while that at the house in Regents Park, a smaller house, is thirty by twenty feet, and has a surprisingly domestic flavour for so grand an interior.

It also has a striking feature not found in any of the precedents we have noted: this is the glazed lantern over the elliptical oculus in the centre of the ceiling which transforms the lighting effects. Sir James Thornhill contrived a somewhat similar effect with trompe l’oeil painting at Moor Park but to achieve it in built form seems to have been too ambitious for the eighteenth century.

The majority of the decoration is on the cove and ceiling which are enriched with rinceaux, shells, cartouches, and arabesques, while the soffit to the gallery is also ornamented with fret patterns, framed rosettes, and rich consoles. The result is one of the most imposing and lavishly ornamented interiors that has been created for a hundred years. The subtle colouring is basically a soft white for the walls and ceiling with light grey in the cove against which the palms and rinceaux are picked out in gold and off white. The columns, cornice, dado, and skirting, are also off white with the addition of twenty-five percent gilding.

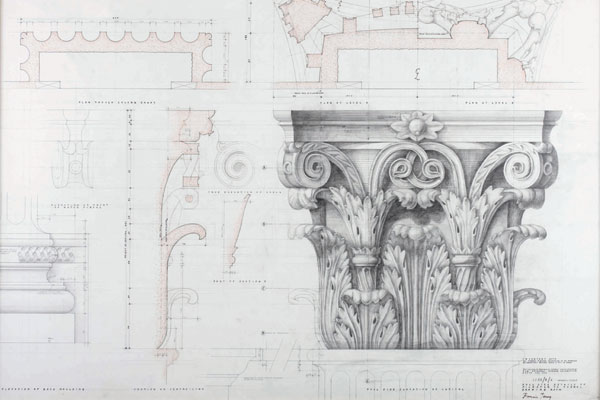

Full-scale, free-hand, drawings by Francis Terry for decorative stonework and fibrous plasterwork made by Locker and Riley have a sensitivity to plant form in classical ornament which is unparalleled in modern British architecture. The frieze of the ground floor is decorated with rich garlands of laurel hanging between candelabra which were inspired by the lavish friezes running in two bands round the interior of the portico of the Pantheon in Rome. Such garlanded friezes were a great feature of Roman architecture, appearing at the Temple of ‘Fortuna Virilis’ (Portunus) in Rome and at the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli.

The eye of the visitor is drawn up in admiration to the oculus, the largest to date of any by Quinlan and Francis Terry. It is surrounded by swags of flowers including roses, lilies, and daisies, which are sculpted full size on the basis of real specimens. The cove is sumptuously decorated with huge shells at each corner as well as with swirling cartouches in the centre of each of its four sides. The craftsmen at Locker and Riley collected a variety of real shells, some from beaches in America, to assist with the initial designs and to capture the correct natural form.

The floor is richly laid in various types of marble, white Statuary, black Belgian, and Brèche Benou, in an elliptical pattern echoing the shape of the oculus in the ceiling. In this, the floor echoes Inigo Jones’s circular marble floor in the Hall of the Queen’s House, Greenwich, laid in 1636 by Nicholas Stone in a pattern reflecting that of the ceiling with a central circle and four roundels. The central chimneypiece of white statuary and Brocatello marble in the Hall was designed by Francis Terry and made by Timothy Lees.

The hall leads into the principal Drawing Room which has a great size and height which make it appropriate for it to be articulated with the rich Corinthian order of the Temple of Castor and Pollux in the Roman Forum. In this the acanthus leaves of the capitals are surmounted below the abacus by volutes or helices of which two are most unusually intertwined at the centre. Acknowledged for centuries as the most subtle and beautiful example of the Corinthian order, this was used extremely rarely by the ancient Romans, though Palladio declared of the three surviving columns in the Roman Forum in I Quattro Libri that, ‘I have never seen any better or more delicately executed work; all the elements are beautifully conceived and perfectly worked out.’

The order has to be deployed in a drawing room in a quite different way from on the exterior of a Roman temple, so at the house in Regent’s Park it appears not as free-standing columns but as fluted pilasters round the walls. Terry has also invented a sumptuous frieze to surmount the pilasters which features acanthus plant scrolls in bunches. These owe something to the carved swags in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican for which the antique precedents include those at two temples: Venus Genetrix (Venus, Universal Mother), Rome, and the so-called Maison Carrée at Nîmes in Southern France, both of which are illustrated in Palladio’s I Quattro Libri.

The superb mahogany doors in the principal Drawing Room and the smaller ones on either side of it have six raised and fielded panels with carved egg and tongue ovolo mouldings, veneers, fielding, and enrichment with waterleaf bead moulding, while their deep reveals have elaborate mouldings, painted and gilded. The gilt bronze door furniture comes from the firm of Schmidt in Paris and the parquet floors follow a Versailles pattern.

English Heritage required Terry to retain Lutyens’s balustraded staircase which had been partially based on the still surviving staircase at Ashburnham House, Westminster, long believed to be by Inigo Jones though now attributed to his pupil, John Webb, in c.1662. Lutyens had omitted the dome and its oval lantern carried on a ring of Ionic columns over a balustraded balcony which had brought an almost Baroque drama to Ashburnham House. Terry, by contrast, reinstated the Ashburnham House elliptical dome with side windows and balustrade, though with Ionic pilasters rather than columns, but richly enhanced with floral carving in the coves.

In the North Passage in the family wing on the east side of the house it was found impossible to place the lift centrally to the side wall, so the asymmetry was concealed by creating two doors, of which the left is false, below a single pediment. This Baroque device was inspired by a pair of doors engraved in Domenico de’ Rossi’s Studio d’architettura civile (3 vols, Rome, 1702-21). This solution of this problem was suggested Quinlan Terry’s wife, Christine, herself an architect.

The richness of the decoration at the house in Regent’s Park is very much a response to the requirements of the patron who took the closest interest throughout the project in the design of every aspect of the house from its elaborate plasterwork ceilings to its handsome door furniture. The architecture and ornament form a link in a chain which we can trace back to at least three sources: to Vitruvius, author of the most widely read treatise on architecture; to Palladio, the most imitated architect in history; and to Inigo Jones, who worshipped at the shrine of Palladio and Scamozzi. It is extended to Baroque Rome and Piranesi, and on to Schinkel, Decimus Burton, and Edwin Lutyens, so the result is a creative theatre of the memory which constitutes the life blood of the classical language of architecture and its ornament. It is thus as pulsatingly alive today as it was over two and half thousand years ago.

Taken from The Practice Of Classical Architecture by Professor David Watkin, Published by Rizolli, 2015