Berlin and Potsdam

Berlin is a great place to visit for a few days. Less than a two-hour flight from London, the city is a manageable scale full of fascinating museums, superb architecture and hundreds of lovely and varied restaurants. Though convenient, it is slightly embarrassing that every supermarket attendant, taxi driver and waitress speaks excellent English. If a Brit spoke with equivalent fluency to the average German, they would be heralded as a linguist.

The most significant work of architecture in Berlin is the now, mainly, demolished wall which brutally separated the communist east from the capitalist west between 1961 and 1989. To some, this is not architecture - it isn't obviously beautiful but if you view architecture as the expression of a culture in built form, then it certainly is. Nothing represents the repressive aspirations of the Socialist Soviet republic so clearly as this almost vanished scar through the city. Traditional cities have had walls for time immemorial, building Rome's wall is a significant part of the Romulus and Remus myth but what was unusual about the Berlin Wall was that it was about keeping people in rather than keeping people out, like turning a bath into a boat. Ironically this is not the first wall of this type. Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713-40) built a wall around Berlin to stop conscripted citizens escaping. Wall building is a big and expensive part of our history and for the most part, our relatively free, liberal and tolerant society has managed to abandon it. The building and guarding of a wall is cripplingly expensive and, as the mightly Soviets discovered, eventually you have to give up and get on with your neighbours.

This is not really my subject and my motivation for coming to Berlin is the architecture which reached its zenith under Schinkel. German 19th-century architecture has a power and presence which seems to reflect the confident vision of Beethoven. Schinkel's Altes Museum has this spirit, with a stark yet sublime facade of eighteen massive ionic columns, which partially reveal and hide a loggia behind that goes through to a rotunda space beyond. I love repetition in architecture, a lesser architect would have felt compelled to add a pediment to tell you where the middle is, but this for me would weaken this strong statement. The ionic is a loose interpretation of the Erechtheum ionic which I know well. The base mouldings though are not from the Erechtheum; they are the early Greek type without a lower torus as suggested by Vitruvius. If any readers know why Schinkel made this rather strange choice please do leave a comment below. It is unfortunate that the loggia is glazed in, and in such an unsympathetic manner, but I can see that preserving the works of art inside would necessitate a controlled environment. For my money, I would replace the originals with plaster casts so that Schinkel's original intention was preserved.

A few hundred yards from the Altes Museum is Schinkel's guard house. Here a highly mannered Greek Doric portico frames the entrance. Schinkel replaces the conventional triglyphs exquisitely carved victory Angels. Abandoning the triglyphs also has the advantage of allowing the columns below to be evenly spaced. With Greek Doric, the corner triglyph makes the end column closer to its neighbour, like at the Parthenon - but no such problem here. The sculpture in the tympanum is carved in the round rather than being a base-relief which makes lovely deep shadows and gives the sculpture far more prominence than its small scale would suggest.

Pergamum Museum

The most impressive site in the Pergamum museum is the Market Gate of Miletus. It was built in Miletus in the 2nd century AD and destroyed in an earthquake in the 10th or 11th century. In the early 1900s, it was excavated, rebuilt, and placed on display in the museum.

There are also other amazing Roman fragments in the same room, enough to make Lord Elgin feel insecure.

Potsdam

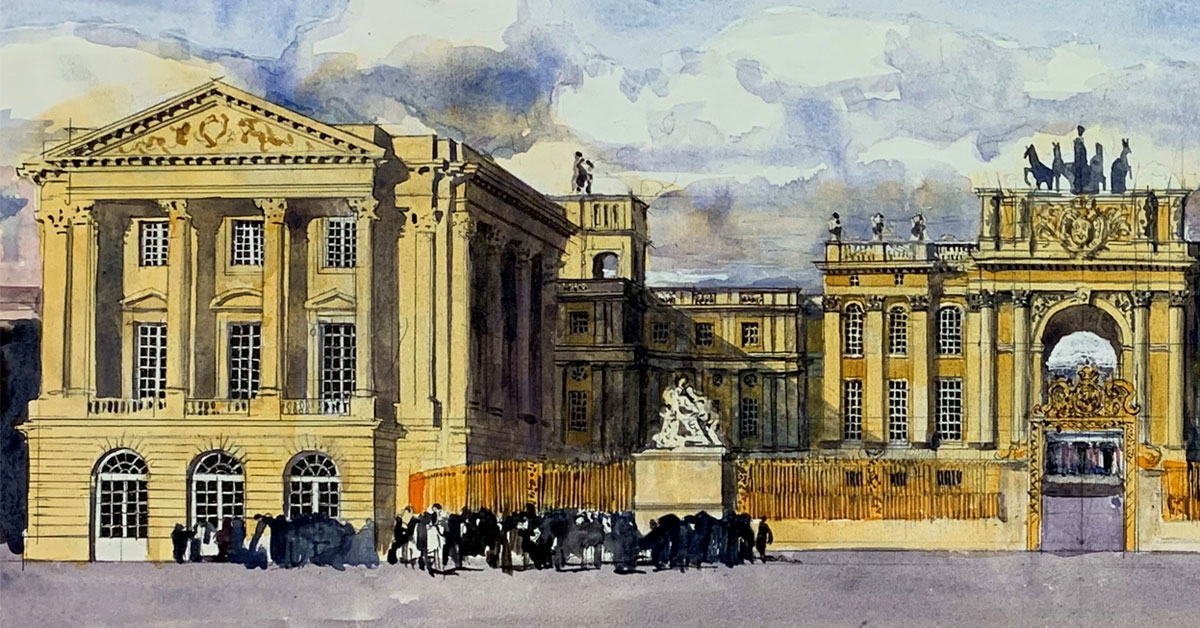

Monarchs seem to enjoy being near their capital but not in it. Paris has Versailles, London has Windsor and Berlin has Potsdam, the country residence for generations of Prussian Kings. Despite this Royal connection, Potsdam has been host to even bigger fish, as it was the place where Churchill, Stalin and Truman came to carve up the globe at the end of World War II and the final time the rulers of the west met a Soviet leader on friendly terms prior to the collapse of the iron curtain almost fifty years later. There's a strange symmetry to this as the matching ill-conceived sweep up, at the end of the First World War, was held at Versailles, but the victorious allies on this occasion did not use the Neues Palais or Sans Souci. Instead, they plumped for the far more modest Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm a few miles down the road. The Cecilienhof is a large dull Art and Crafts house with no charm or architectural interest. I would be so interested to know the thought process behind this choice, perhaps the rococo decoration would be too Tsarist for Stalin's taste or maybe the site of the victorious leaders living it up in a German royal palace was seen as tactless when the people of Berlin were destitute and many were starving.

The Neues Palais or New Palace is the main royal residence in Potsdam. It is an elaborate baroque affair similar to Castle Howard yet on a vast scale. The entrance is framed by two ornate villas which are joined by a curved Corinthian colonnade.

On the garden side is a straight avenue on the centreline of the palace which is about half a mile long. The monotony of this makes one hunger for the meandering informality of William Kent and Capability Brown. On one side behind some trees is an extraordinary Chinese Pavilion covered in gold and further away on the other side is Sans Souci, a rambling baroque bungalow packed to the gunnels with rococo knick-knacks. This is where Frederick the Great played his flute and chatted to Voltaire.

My favourite story about the pair is this cryptic invitation sent by Frederick the Great to Voltaire, inviting him to dinner:-

Read out in French it says 'venez sous (under) 'p' à cent (100) sous (under) six (6)', which sounds like 'venez souper à Sans Souci.' (Come for supper at Sans Souci).

Voltaire replied with simply with two letters 'Ga' which is 'G grand, A petit' (large G, small a), pronounced in French j'ai grand appetit! Which means "I'm very hungry".

Very witty, even for Voltaire.