An Introduction to British Architecture from Queen Victoria to George VI

My blog this month is two in-house lectures I have given to my office over the past few weeks. Originally, I intended to cover the period from Queen Victoria to World War II in one lecture. But unsurprisingly this proved impossible and so the first is Victorian and Edwardian Architecture and the second is English architecture between the Wars.

Lecture 1: An Introduction to Victorian and Edwardian Architecture

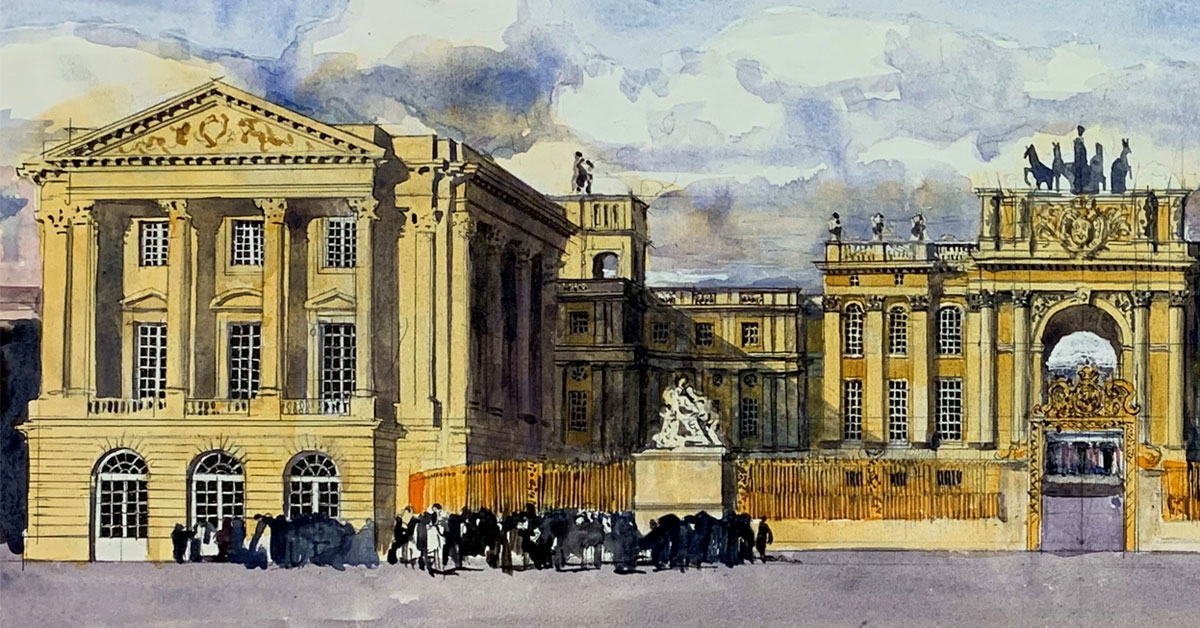

The Victorian age inherited the battle of styles which defined the end of the Georgian era, a battle which was not convincingly won by either side. Gothic, Classical and even Mughal style architecture were all available to patrons and architects. To the serious-minded Victorian this was all too whimsical and they searched for a style which would be appropriate for their times so that the others could be dismissed. The chosen style was Gothic, and theorists were not shy of giving this stylistic preference a moral dimension. Pugin was the first to do this in his book ‘Contrasts’ where he compares the morally bankrupt world of classical Georgian England with a romantic view of medieval England which he saw as a golden age both socially and architecturally. John Ruskin followed these ideas returning from Venice with seductive sketches of Gothic and Byzantine details which he contrasted with the repetitive and mechanical nature of Georgian speculative housing. Gothic began to be seen as ‘true’, morally upright and Christian, while Classicism was seen as false, immoral and pagan. William Morris took these same ideas and reproduced them in wallpaper, stained glass and furniture. Because of this many of the greatest and most ambitious buildings of the Victorian age, including The Houses of Parliament, Tower Bridge and the Natural History Museum were all designed in the gothic style.

Despite this ideological push for Gothic, Classicism persisted throughout the Victorian age on a scale never dreamed of by the Georgians and rivalling the great works of Ancient Rome. The Albert Hall, Leeds Town Hall and St George’s Hall, Liverpool are all evidence of this trend.

This classical undercurrent grew into the dominant and triumphant style of Edwardian Baroque during the early years of the 20th century. The confidence of classicism suited the times and as John Singer Sargent represented the glamour of the age in virtuoso brush strokes, Lutyens, Belcher and Bloomfield captured the times in brick, marble and stone.

Lecture 2 An Introduction to British Architecture between the Wars

It is hard to imagine the decimation caused by the First World War. Understandably, a growing number of people started to feel that there was something terribly wrong with a civilisation which caused young boys from neighbouring countries to commit murder for a purpose that no one really knew or understood. Politics, religion and art were now seen as culpable. A full-scale rejection of traditional values ensued, first by the Avant Garde and then slowly but surely by the population at large.

In art this started with the Italian Futurist Marinetti. His desire was to wipe away all forms of tradition and live in a brave new modern world of machines and speed.

‘Destroy the Museums. Crack syntax. Sabotage the adjective. Leave nothing but the verb.’

These ideas were taken up by Marcel Duchamp who in 1926 called a urinal a work of art, signing it R.Mutt, the French equivalent of Joe Bloggs. By titling it ‘fountain’ and placing this crude object in a refined art gallery in a position one would expect a Canova or Bernini he was deliberately mocking the great works of the past and in so doing attempting to free society from their hold. Le Corbusier and Gropius took these ideas into architecture

With these revolutionary views also came a disdain for ornament. The architect Adolf Loos published an essay titled ‘Ornament and Crime’ where he suggests that the amount of ornament a society uses is inversely proportion to its level of civilisation. Primitive tribes ornament everything, their canoes, oars and themselves with tattoos. As we progress, he argues, our need for ornament diminishes.

Despite all these ideas being in the air in mainland Europe, they made little impact on English architecture. Things continued as they were, although in a more chaste manner.

After the Second World War modernism came to dominate almost all British architecture. In Warsaw the damage caused by bombing was replaced by a faithful copy of what was there before but in London a different approach was used. Instead of replacing like for like, overtly modernist buildings were built and the taste for modernism was so strong that tower blocks were built out of choice instead of traditional terraces. The architectural establishment and successive political leaders saw modernism as the solution to the problems of the day. With the exception of a few cases like Clough Williams Ellis’s Port Meriam and Steven Dykes Bower’s Baldacchino at St Paul’s, Classical architecture was all but wiped out and would not return for several decades.