The Making of the Erechtheion Capital

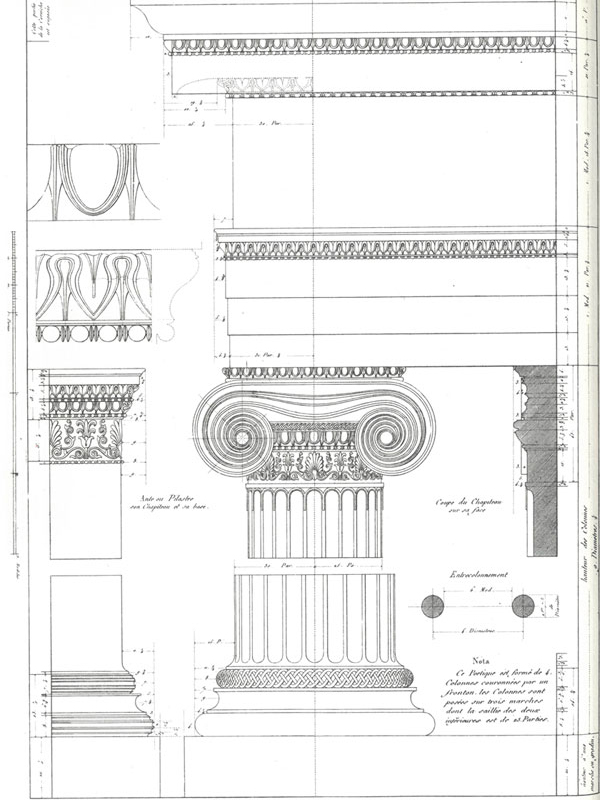

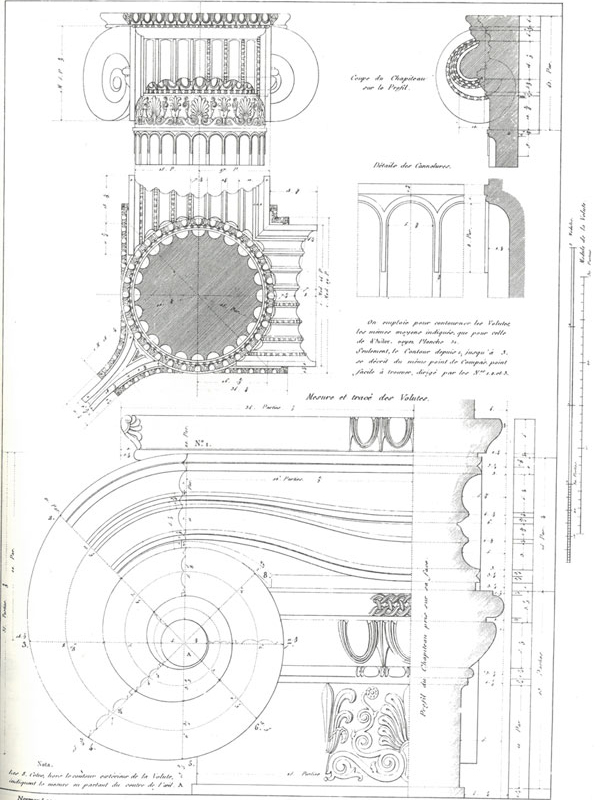

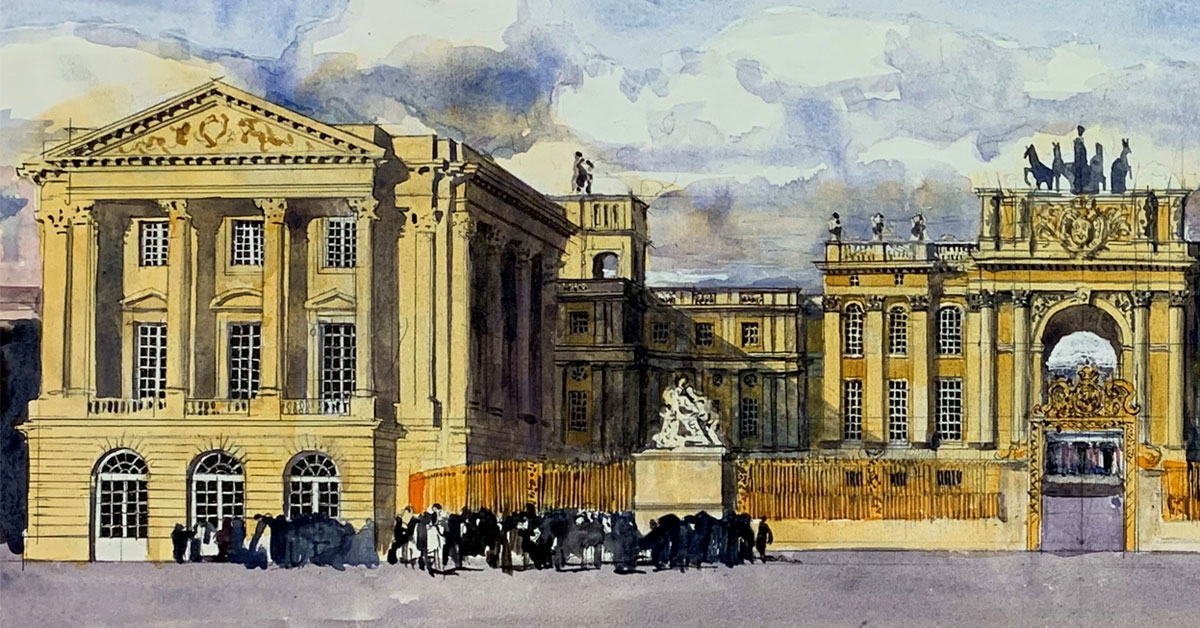

One of the most universally adored details of all classical architecture is the Ionic capital at the Erechtheion on the north side of the Acropolis, built between 421 and 406 BC. Phidias was both sculptor and mason of the structure and was employed by Pericles to build the Erechtheum and the Parthenon. The capital is a work of such beauty and sophistication that it has been much copied by architects throughout Europe and America from the late 18th Century onwards, following the publication of measured surveys of the Erechtheion by Julien-David Le Roy in France and Stuart and Revett in England. This beautiful classical order was on the following buildings:- Litchfield House, London(1761); Downing College, Cambridge (1806-1811); Baltimore Cathedral, Maryland (1806-1821); St Pancras Church, London (1816-1822) and the Pushkin State Museum, Moscow (1898-1912)

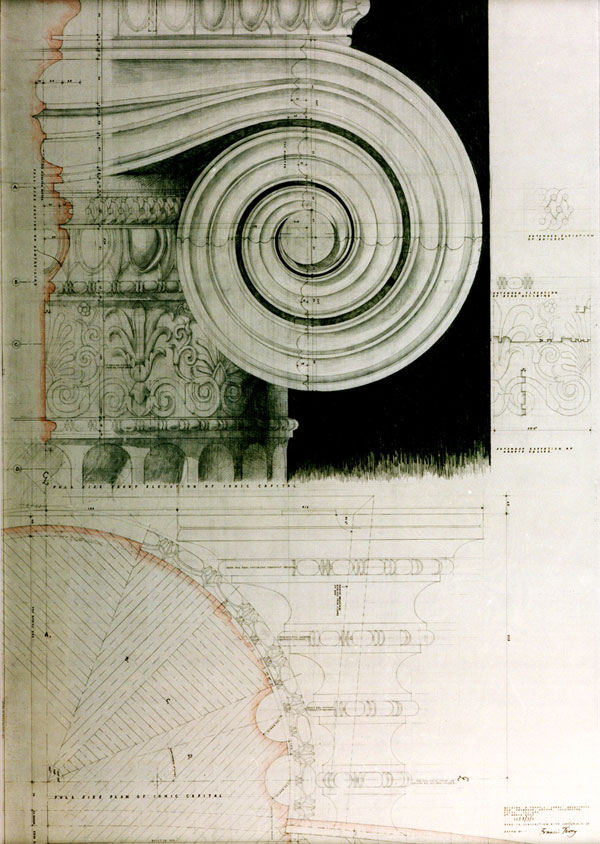

The appeal of this capital comes from the combination of flowing lines and strict geometry with ornamentation which makes a satisfying play of light and shade, designed to look its best under Mediterranean sun. The volutes are unusually complex, being made up of a complicated profile which gradually diminishes towards the centre of the spiral. Despite the level of decoration, the overall appearance does not look cluttered or busy.

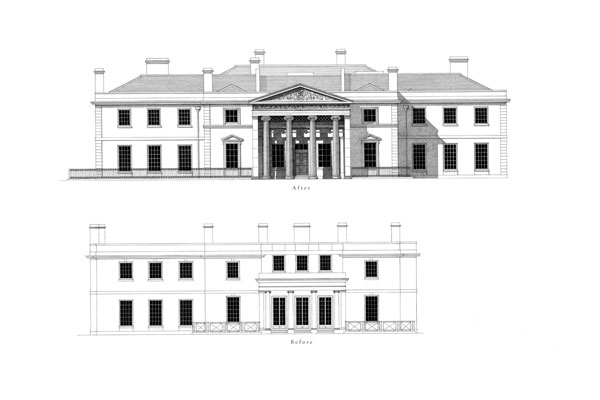

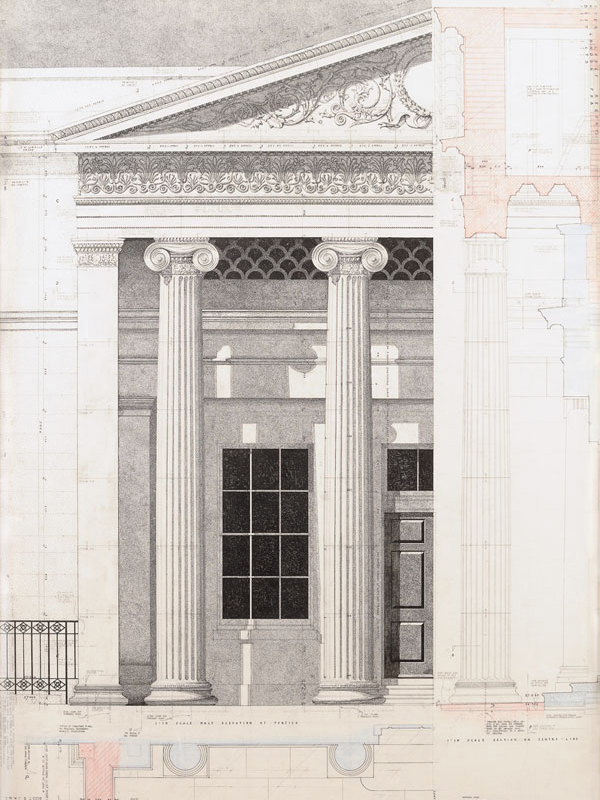

When working with my father, I designed and drew out the portico for Hanover Lodge in Regent’s Park. I decided to follow the Erechtheion, rather than Palladio which was the usual choice of the practice. I made a study of measured drawings of the Erechtheion and looked at one of the original capitals in the British Museum. My intention was to draw a version which was as close as possible to the original.

The final capital was made in precast concrete and a craftsman made the original former for the mould out of a variety of materials including MDF, car body filler and zinc sheets. I enjoyed the use of modern materials and techniques to make a beautiful form, from the ancient world. Concrete is usually seen as an ugly modern material and I enjoyed the process of making it look beautiful and ancient.

Copying a capital from a temple to gods who are no longer worshipped or believed in and designed by architects who lived thousands of years ago, may seem a strange venture. How can this be remotely relevant to us in the 21st century with our aeroplanes and iphones? On one level I am slightly surprised that these forms do have such a strong meaning to so many people. To a certain extent, the enjoyment of these ancient forms comes from a desire to be part of a tradition that goes back thousands of years and to feel a connection to our ancestors, who though very different, shared so much with us. In working out the intricacy of egg and dart, guilloche or volute diminution of the Erechtheion capital my mind followed the same pathways of Phidias all those years ago, and gives me a direct insight into the mind of one of the greatest artists of the classical world.