Happy Birthday Mr Lutyens

As everyone knows, the 29th March this year is a big day in European politics, but, if like me, you feel bored by the process and anxious by the result; you perhaps need a distraction to tide you through these troubled waters. Might I suggest celebrating 150th Lutyens’s birthday, which coincidentally is on the same day.

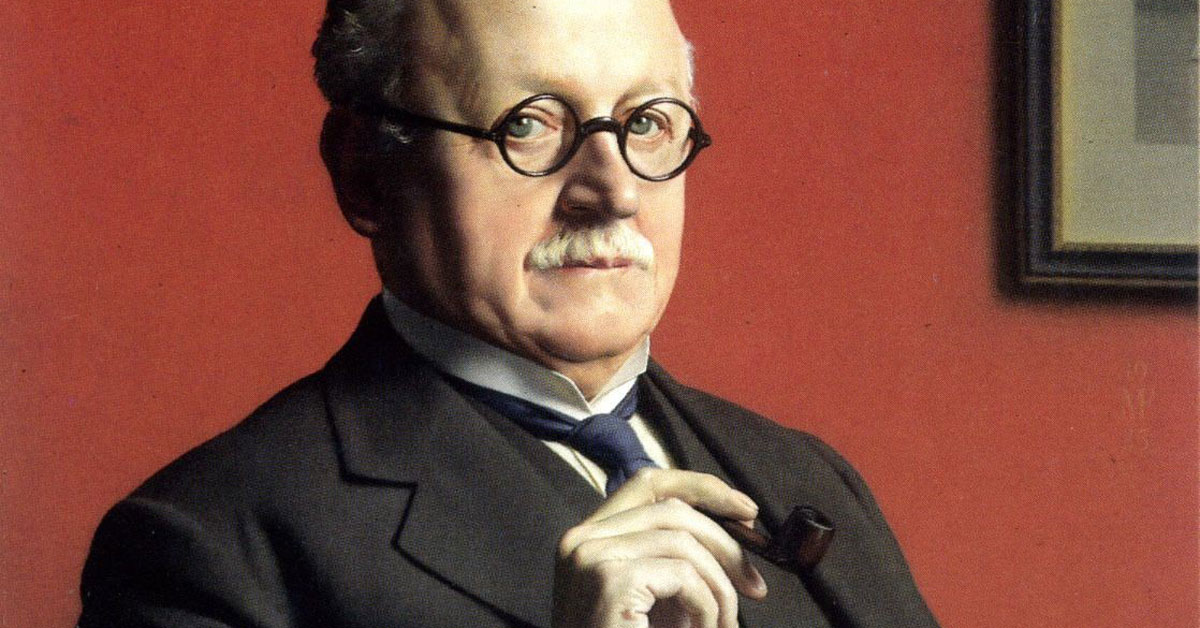

Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869 - 1944) is one of the greatest English architects, perhaps second only to Wren and to some he is even his superior. His early houses were cottage-like in style and come out of the Art and Crafts movement which must have been a welcome relief from the overly ornate pomposity of Victorian architecture. His collaboration with the great garden designer Gertrude Jekyll ensured that their houses seamlessly melted into their surroundings. These houses have become a backdrop to a certain view of England with its red postboxes, tennis on freshly rolled lawns, sleepy branch line stations, and vicars in Panama hats. E.M Forster’s Windy Corner from ‘A Room with a View’ is surely an early Lutyens house.

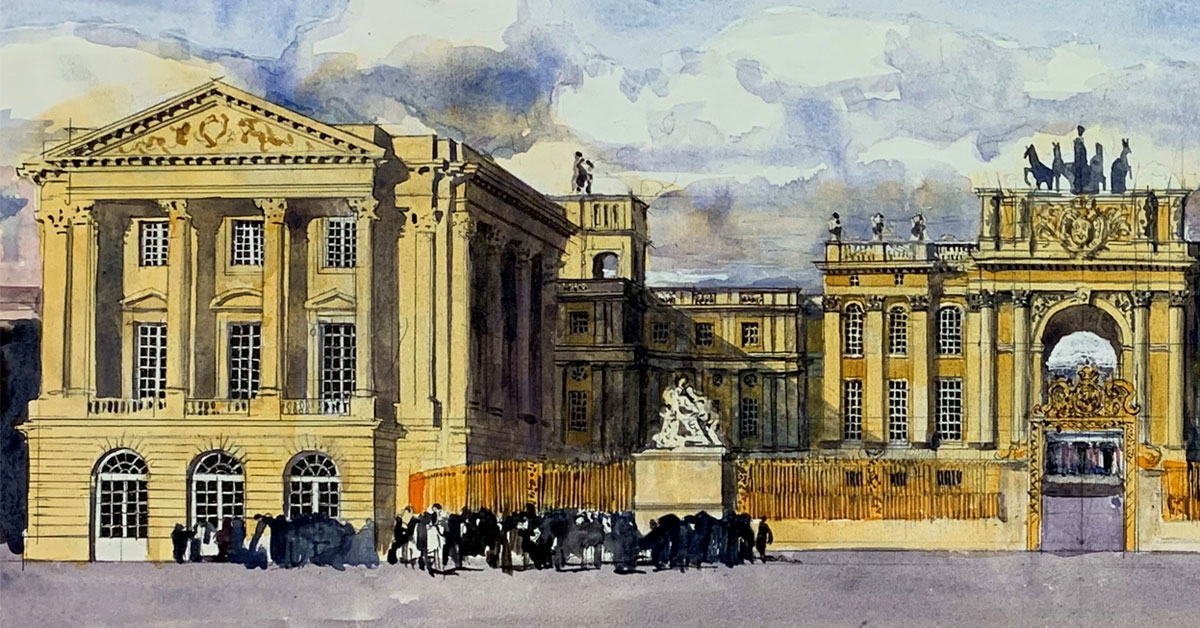

He later embraced classical architecture, describing this revelation as his ‘Wrenaissance’, spelt with a ‘W’, a characteristic Lutyens pun, to emphasise his debt to Sir Christopher Wren and perhaps to say that his style was more Stuart than Georgian. Lutyens’s largest and most prestigious work was the Viceroy’s house in New Delhi designed as a melange of European Classicism, Indian Mogul style with many touches and inventions of his own. Ironically this ambitious work was completed only eighteen years before the end of British rule in India.

Lutyens’s last projects were First World War memorials, here Lutyens takes the language of classicism and gives it his own voice. His cenotaph, a small yet profound work, honours the dead with dignity and without being jingoistic or religiously dogmatic. It is perhaps the greatest of all war memorials, still relevant today and yet so of its time.

I came to appreciate Lutyens quite late in life, I grew up believing that great architecture had to be pre 19th century and the earlier the better. It was as if the history of architecture was like a battery losing power as time passed. When Lutyens came up in conversation, my father always would say that his mentor, Raymond Erith thought that Lutyens was an amateur, and so I never really looked at his work. In many ways he was an amateur, he had clients from a young age and so he was by necessity self-taught, but was that such a bad thing? The word ‘amateur’ comes from the same root as the word ‘amore’ - how much better to do things for love rather for money, which is the unfortunate fate of all professionals. Technically Lutyens was not an amateur, with a large family and an aristocratic wife used to the finer things of life, he needed all the money he could get. Although what I think Erith meant was that he was untrained, but is a formal architectural education such a great thing? It often leads architects to spend their lives trying to please other architects or long dead tutors from their student days, forever seeking the dramatic early success of some irrecoverable crit. The untrained amateur has no such faded glory to revive, they approach building with an uncluttered mind, seeing with the clarity and joy of a child. This was Lutyens’s approach as he went through life cracking silly puns, drawing lighthearted cartoons and designing buildings full of warmth and wit.

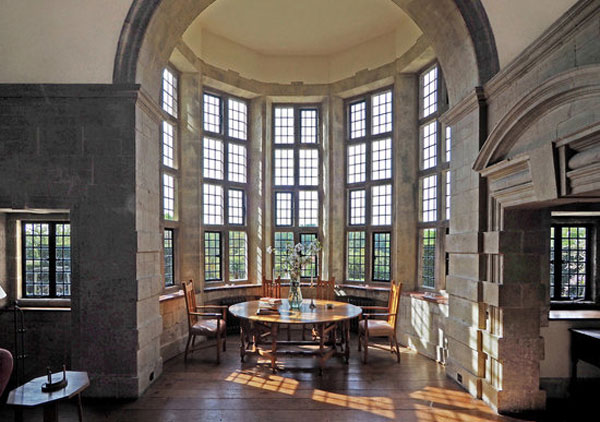

My first contact with Lutyens came when I was working for Allan Greenberg in Washington DC, although I had stayed at Lutyens’s British School in Rome only a few months before, it had little impact on me. Greenberg was a fan and that put him on the radar for me. While there I visited Lutyens’s British Embassy and when I came home, I started to notice clever little details like the broken corner topped by a sculpture at Finsbury Circus of which Greenberg had a photo in his office library. On a trip to India with my father in 1992, we visited the Viceroy’s house in New Delhi and I can remember the use of red, beige and purple sandstone with simple abstracted mouldings, it seemed the natural heir to the Red Fort at Agra and Fatehpur Sikri. A few years later I visited Bois de Moutiers on a holiday to Normandy which was a turning point. This, I felt, had the ingenuity and freedom of Frank Lloyd Wright with the charm and cosiness of traditional detailing.

Lutyens was in the last generation of traditionalists whose flame was snuffed out by Second World War. In the years that followed, modernism became seen as the only way to build a better world free from the shackles of tradition. There was an understandable desire to switch the plug off at the wall and start again. Lutyens was just too old hat and it seemed that he was destined to be forgotten, although, in these dark days, the arch-modernist Basil Spence did prophesy a Lutyens revival, which seemed absurd at the time. But he was right, during the ‘80 his fate did indeed change, culminating in Robert Venturi including him in his book “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture” and from then he became the godfather to the postmodernist movement and his rightful place in history was assured.

In my practice, Lutyens is becoming increasingly influential as some of my clients prefer the more relaxed quality of his early work to full-blooded classicism. Working within this style allows us to design informal plans which are sometimes better suited to a particular client’s requirements. The use of asymmetry allows us to use quirky elements like oval windows without the need to slavishly repeat them. His rich palette of materials combined with clever construction details gives the architecture a richness which we try to emulate. As Lutyens had a ‘Wrenaissance’ I am perhaps having a ‘Lutyaissance’.