L'amour de l'Architecture Française

Over the years I have noticed that clients seem to favour French classicism over Italian. Because of this, I have been sent on several trips to Paris to study and measure buildings – it’s a tough job but someone’s got to do it!

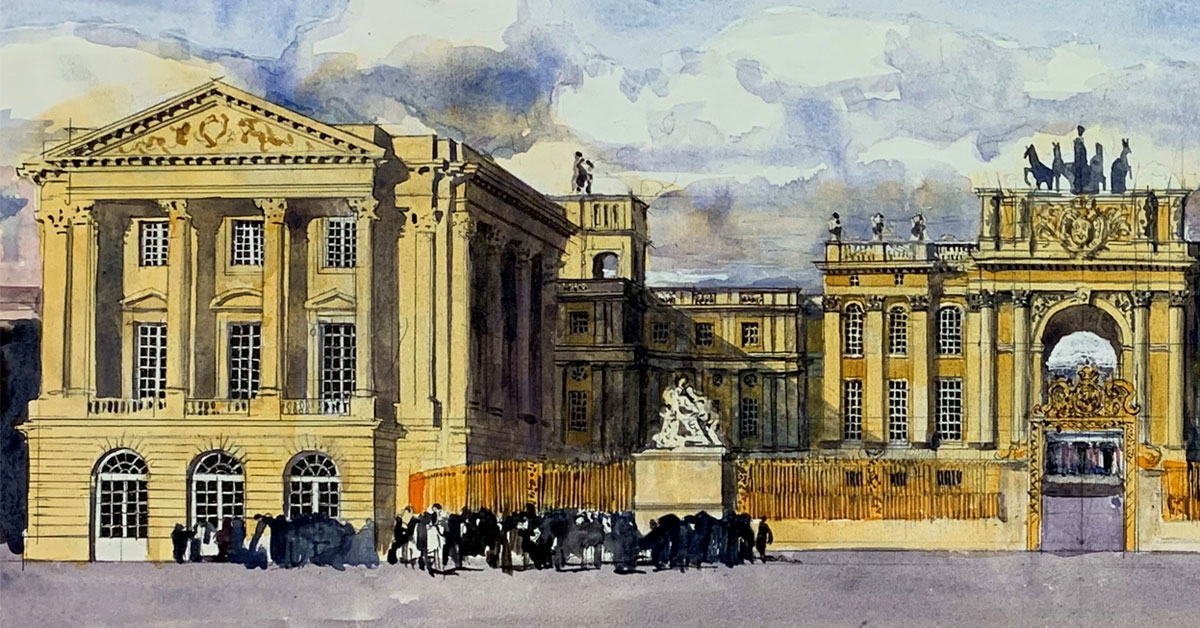

I can certainly understand this preference; French architecture has a sweetness and a lightness of touch which the great works of Italian architecture sometimes lack. The curves (and this includes everything from the shape of an extensive lake to the tiniest architrave moulding) are often a freehand gesture, which, like the curves of the human body, cannot be plotted by a compass or worked out geometrically. French panelling illustrates this beautifully where curves confidently meet right angles with no apparent rhyme or reason and the effect is both charming and completely resolved. There is a language of ovals (in preference to circles) and sculptural elements which integrate so well with their settlings that they become an essential part of the architecture rather than a mere last minute add-on.

This sensual approach to architecture is particularly effective when applied to three-dimensional forms, like staircases, of which the French have always been masters.

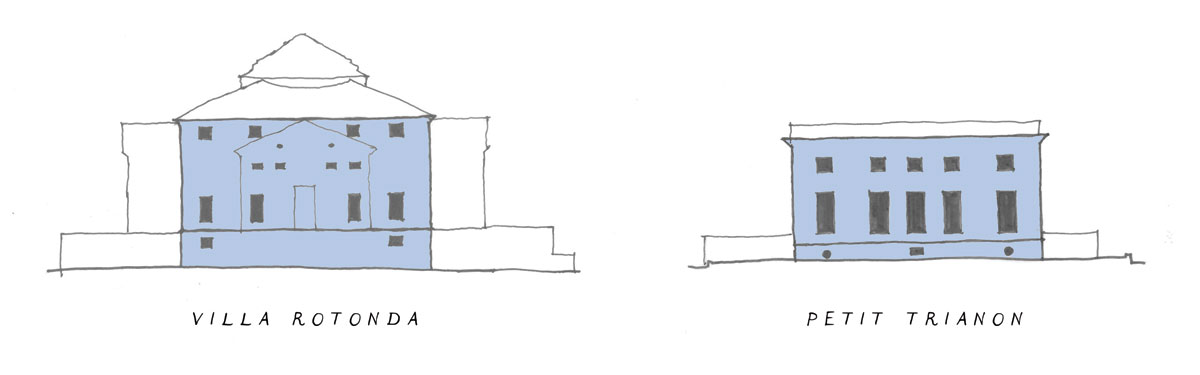

French architecture also accommodates huge windows, far larger than the ones at Palladio’s villas. This aspect of the style is understandably popular with most clients who are far more interested in light and space than stylistic pedantry. Having made a simple comparison study I noticed that Palladio’s Villa Rotunda is 7% window and Gabriel’s Petit Trianon is a wapping 19% - I know which one I would prefer to live in.

Something I love about French architecture is the repetition. Palladio and the Palladians perpetually overemphasise the middle of a building with a four-columned portico. The French classicists did not do this so often. They, like Vivaldi, understood the power of a repeated chord.

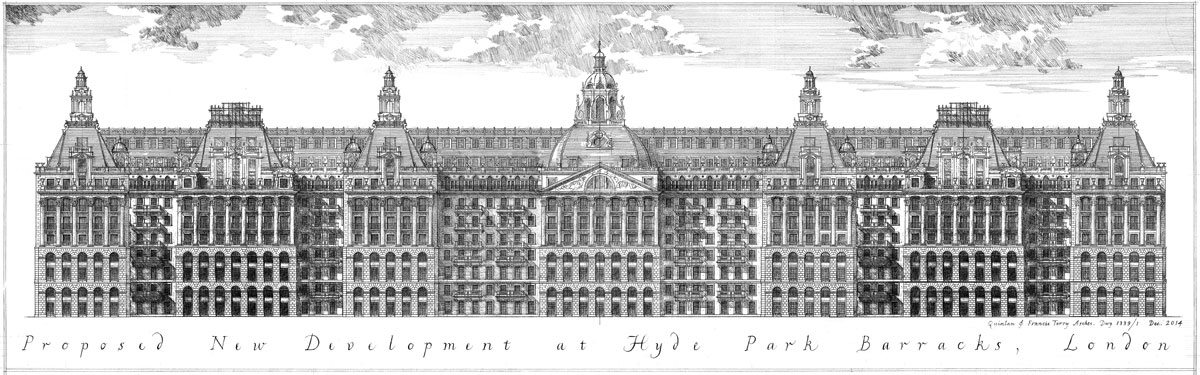

Our first flirtation with the French style was a house we designed in 2012 and my design for a huge new development at Hyde Park Barracks.

English architecture has always owed so much to French architecture, and this can be seen in the amount of English architectural terms, for instance: - chimney, truss, jamb, dormer, vault, mansion, terrace, and masonry which all have an old French origin. We did not bother to translate words such as Parterre, oeil de boeuf and Tas-de-Charge. This was probably because of French masons during the cathedral building frenzy of the middle ages or perhaps it went back to the Norman conquest.

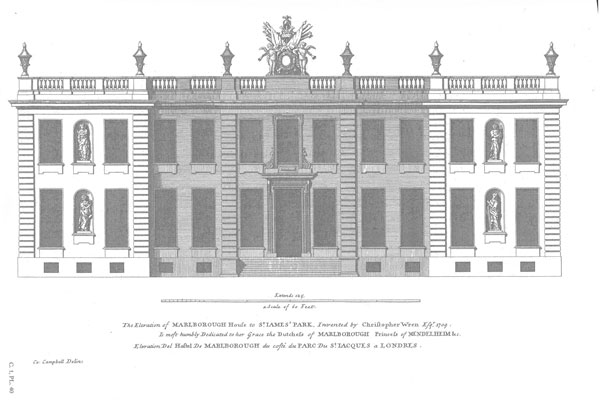

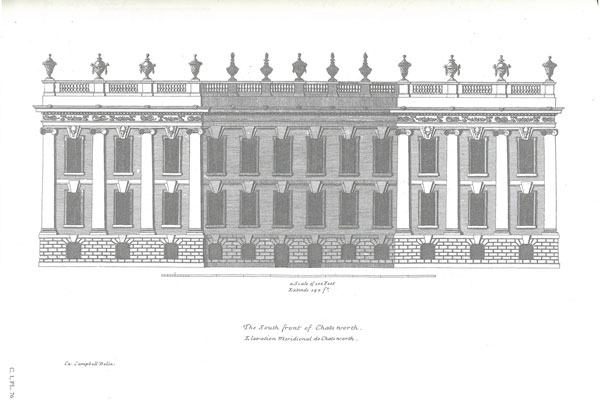

This influence has been almost continuous and was particularly important when England, as a relative latecomer to the party, was fumbling through to form its own style of classicism. This period coincided with the dominance of Louis XIV’s court which meant that a taste for all things French came to inspire English architecture. Italy, despite being the origin of classicism, seemed less relevant at the time and so it is not surprising that, in the work of Sir Christopher Wren, we do not see the sublime yet almost crude simplicity of Brunelleschi or Palladio, nor do we see the curves of Bernini or the brilliant eccentricity of Michelangelo or Borromini. Wren never went to Italy and his work seems to echo more the French architecture he saw in Paris in 1665-66. The Vitruvius Britannicus image of Wren’s Marlborough house could easily be a design by Hardouin-Mansart or Blondel. This French flavour is evident in many of the great houses of the 17th and early 18th Century. Petworth, Chatsworth, Castle Howard and Easton Neston all have this quality to a greater or lesser extent.

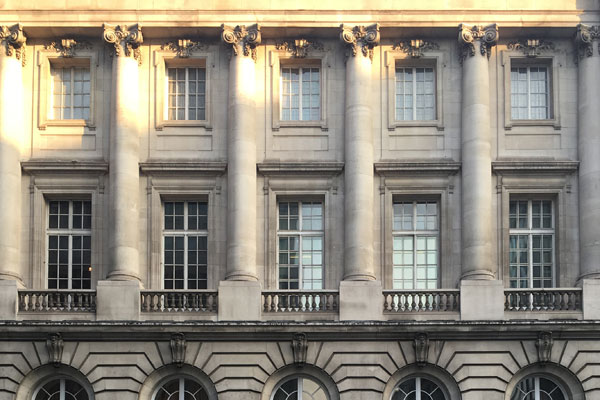

With the Hanoverian ascendancy, perhaps to distinguish itself from the French-influenced Stuarts, there was a conscious swing back to Italy and specifically Palladio which they saw as the uncorrupted source of Classicism. This did make a significant change and explains the use of smaller windows, but even they had some decidedly French tendencies. Peckwater Quad, Oxford, despite being a seminal Palladian work, has similarities to the garden façade of Versailles rather than any work by Palladio.

Concurrent with the Palladians, England also had its own contribution to the Rococo movement, a style which was effectively born in the Court of Louis XV. A major French revival occurred in the mid-19th Century and was a dominant force up until the First World War. This was, in part, due to the construction of Waddesdon Manor (built 1874-1809) in a French Renaissance style. The taste came to be known as the Goût Rothschild and came to influence both England and America. This and the Edwardian taste for opulence led to the French architect, Charles Mewès, designing some of the most recognised buildings of London including the Ritz Hotel, (1905-1906) and the Royal Automobile Club, Pall Mall (1910) both in an exuberant French style.

When I set up my practice, friends and a few journalists asked whether I would continue with the Palladian style, would I be doing more of the same or would I change direction completely? Some people, hoping for a Road to Damascus conversion, were thinking perhaps I would become a modernist. I would always answer these enquiries evasively because at the time I did not know how I would change, although, I knew I would. Having studied French Classicism, I am beginning to see what our office style may become. I am not saying that I will fully adopt the Goût Rothschild, but I will certainly have un accent Français.