St Andrew’s Felixstowe – The Last Wool Church

Killing time with a friend while waiting for our respective son’s football match to start, we sneaked into nearby Felixstowe for a hearty English breakfast. This was a little ritual we used to do, before his son was injured and taken off the squad. Despite living near Felixstowe, I had hardly ever been there and so it was something of a novelty. On our way back to the car, ambling past mock-Tudor semis and privet hedges, we happened upon Raymond Erith’s stark uncompromising concrete church, which I vaguely knew but had never seen in the flesh.

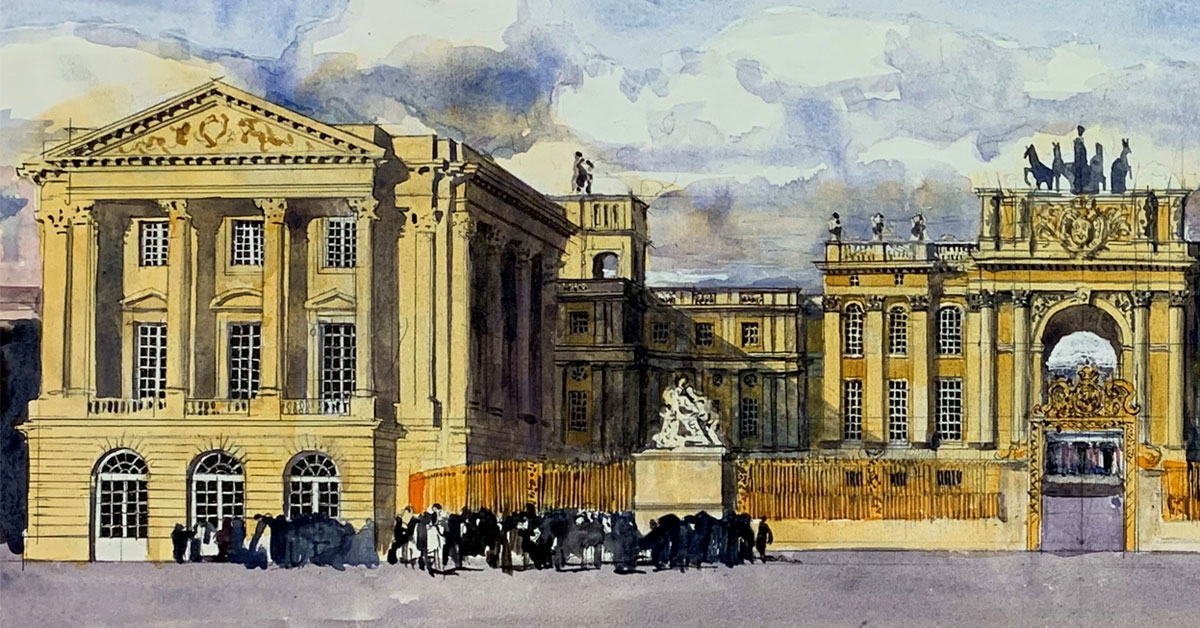

St Andrew’s, Felixstowe is an uncharacteristic early work by Erith designed between 1929 and 1930. He worked in collaboration with Hilda Mason, who, as the older architect was probably the dominant force in the project. It was the first church to be built in England using reinforced concrete and is in the form of an East Anglian wool church. Medieval churches like Dedham, Blythburgh, Southwold and hundreds of others are of a similar form but built in stone and timber instead of concrete.

It was commissioned by Henry Greene, the vicar at the time, who wanted a statement of ‘Protestant triumphalism’. A tricky brief, which has, since the reformation, perplexed architects and clients alike. Protestantism was formed in opposition to the architectural triumphalism of the Catholic Church with their sculptures, ornament and lavish use of materials. They needed to make a noise but do it quietly. In this way St Andrew’s is successful and I can see how the chaste and severe style would appeal to ‘hearty middle-stumpers who despise “all the inessentials of the Faith”’ - to quote Betjeman, nothing inessential here apart from an rather gaudy resurrected Christ at the east end.

Being made of concrete, the outside has not fared well, cracking to reveal rusting reinforcement bars which made me wonder how long it is going to last. There is also a complete lack of ornament which gives the church an almost brutalist feel, but years before the style came to prominence. For me, the interior looks much better than the outside, the grey concrete harmonises with the oak parquet floor and pews and has that rare and magical quality of looking both ancient and modern at the same time. Originally it had brightly coloured stained glass windows in a hexagonal design. These unfortunately have been removed and replaced with plain glass because Henry Greene felt it made the church look like an Italian ice cream parlour. I would have love to have seen it then, or for that matter the ice cream parlours he was talking about.

It is an uncharacteristic work by Erith and by all accounts he was slightly embarrassed by it. It was designed at a time when classicism and modernism could be pursued together, before they became polarised after the war. Erith often thought to be a ‘progressive classicist’ was using a modern material combined with the traditional architectural forms which he loved. It is an interesting experiment to show the potential of concrete as a poetic material. It left me with the feeling that, perhaps because of weathering, modernism usually works better for interiors than exteriors. It is certainly worthy of its grade 2* status, perhaps it should be grade 1. It is, after all, the last flowering of the great and ancient wool church tradition and I doubt there will be any more.