Stowe Revisited

School reunions can be stressful, 'dress informal' says the invitation, but how informal? I’d almost rather the invite requested, 'school uniform'. At least they didn’t demand 'smart casual' – whatever that is. After much indecision, I headed west to Stowe, my old school.

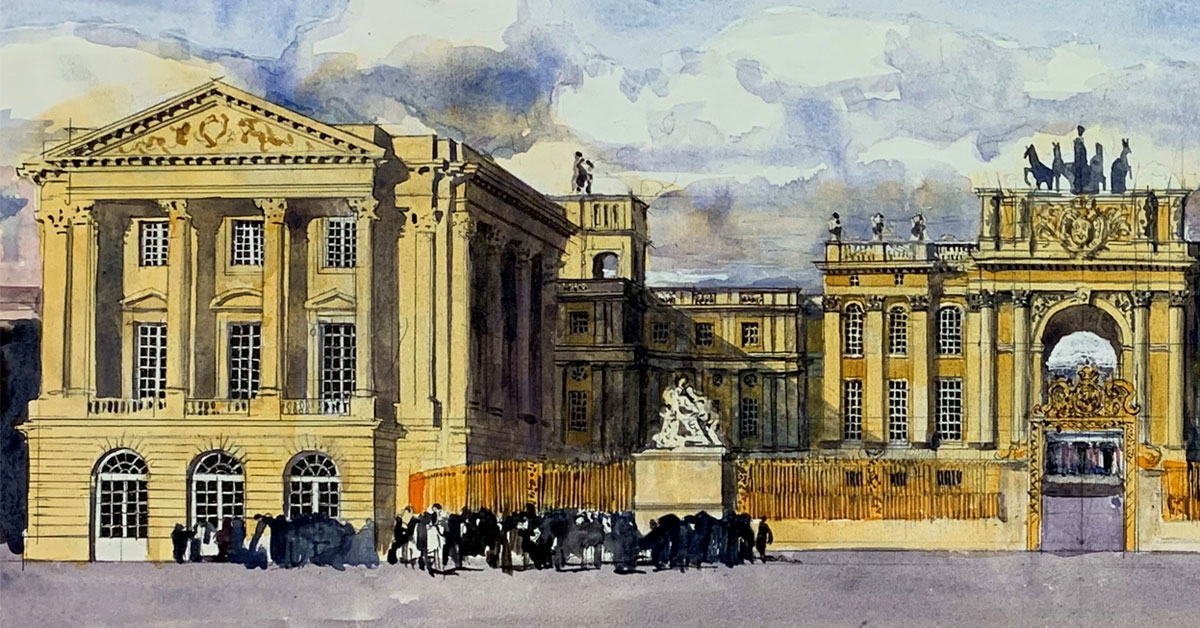

Stowe is arguably the most beautiful house and garden in the country. Built by the Dukes of Buckingham, employing all the greatest Georgian architects, starting with Vanbrugh, Kent and Gibbs then on to Adam and Blondel then ending with a rare essay in Gothick by Soane. As I drove up the long drive seeing the Corinthian Arch in the distance and then over the Oxford Water, framed by two Gibbs Pavilions, all fear of justifying the intervening decades melted away in the presence of such beauty.

When I studied there, the school still owned the house and garden and as a consequence, the whole place was falling apart. Trees were growing through some of the garden temples, ivy, nettles and brambles were everywhere and the whole place had that atmosphere of Piranesian faded glory. The house itself was not much better, unhelped by unruly pupils. I can remember a stray fork flying through the air, piercing an ancestral portrait in the dining room one evening at supper. This state of decay could not last and fortunately, the National Trust came to the rescue. And come to the rescue they certainly have; the place looks immaculate and it is wonderful that we still have people with the skills to carry out this work.

After a brief speech from the headmaster, under the South Front portico, I found some old friends and with a few bottles of prosecco we went down to the Elysian Fields. The grounds looked heavenly in the late summer sun. I love this particular place, the Temple of Ancient Virtue seems to speak to the Temple of Worthies over a small lake with a rustic stone bridge. It is surely William Kent’s greatest creation. The landscape, which looks so natural, is an utterly contrived work of art involving moving hills, creating lakes and planting vast numbers of trees in strategic positions. In this way, Kent, ever the artist rather than a true architect, was designing a series of three-dimensional landscape paintings, ‘replacing oils on canvas by leaf and stone’ (to quote a paperback guide). This way of structuring landscape as asymmetrical compositions is an idea which has been borrowed for gardens and parks all over the world ever since. It also appears on everything from Spode blue and white tableware to Toile de Jouy wallpaper and fabrics. More recently, kidney-shaped swimming pools and golf course layouts have the same source, but I am sure Kent would be happy if that was left unsaid.

This got me thinking, why does this style of landscape have such universal appeal? It is, without a doubt, the greatest English contribution to the visual arts, and what a massive contribution it was. It is loved by people all over the world, even by those for whom this setting is not anything like the landscapes of their home. I wondered whether there is something inherent which makes a strong connection with our emotions.

A theory put forward by Denis Dutton is that our love of this type of setting is due to its similarities to the Pleistocene Savannah’s in which we evolved. The presence of open spaces, low grass and copses of trees interspersed with rivers and lakes reminds us of where we lived hundreds of thousands of years ago. It is somewhat ironic that when the architects of the Georgian era were trying to recreate imaginary classical landscapes, they accidentally recreated a far more ancient setting which is both everyone’s ancestral home and our natural habitat.