Jefferson’s University of Virginia

'Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ - the infamous line penned by Thomas Jefferson has a lovely ring to it. A right to ‘life and liberty’ I can understand, but ‘pursuit of happiness’, seems more like a personal project than a ‘right’. For some, it may be travelling the world, for others walking a dog, collecting stamps or whatever it is that suits your particular taste. If it was not so familiar, I would find it curious that this much-quoted line of poetry has found its way into the Declaration of Independence where one would expect dry legal clauses.

Jefferson adapted this phrase from John Locke’s dull but functional ‘life, liberty and estate’. There is something in the rhythm and the sound of Jefferson’s version which is both satisfying and memorable. From this, I feel, it is no surprise that Jefferson was a great architect because he had an instinct for elegant phasing, which is the essence of all good architecture. His design of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville is not just functional rooms and spaces, but rather an exceptional work of architecture, embodying the same sound judgment which he used to structure sentences.

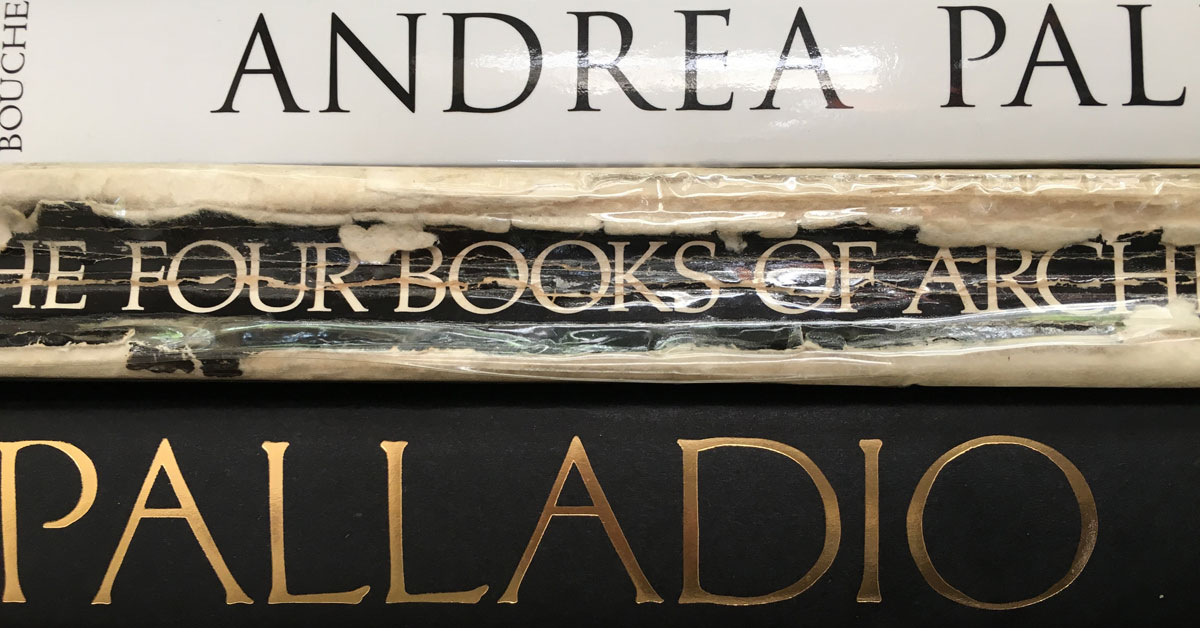

I recently visited the University of Virginia, and despite the rain, I found it a charming work of architecture. The materials are simple and making the most of what was available in such a remote place at the time. Jefferson’s crude architectural drawings rendered on pieces of squared paper look childish and amateur. His genius was to use Palladio’s Four Books, which he referred to as ‘the bible’. What he followed most closely were Palladio’s orders in Book One and his measurements from Ancient Rome in Book Four.

There is a straightforward common-sense quality to Palladio’s Book which must have appealed to Jefferson. It portrays an architecture for ‘solid chaps’, rational men, in contrast to the superstitious and sensual baroque. In creating an architectural style for a new republic, Palladio’s Roman measurements was the obvious choice. This mirrors similar attitudes that the Wigs, only a few decades earlier, followed when they searched for an ‘English’ style to bolster the somewhat tenuous Hanoverian succession. It was this very dynasty, who Jefferson gained independence from, and so it is somewhat ironic that both the oppressor and the oppressed followed the same architect.

I know nowhere else where pages of Palladio’s Four Books have been so faithfully copied. Here are some examples which I noticed while walking around.

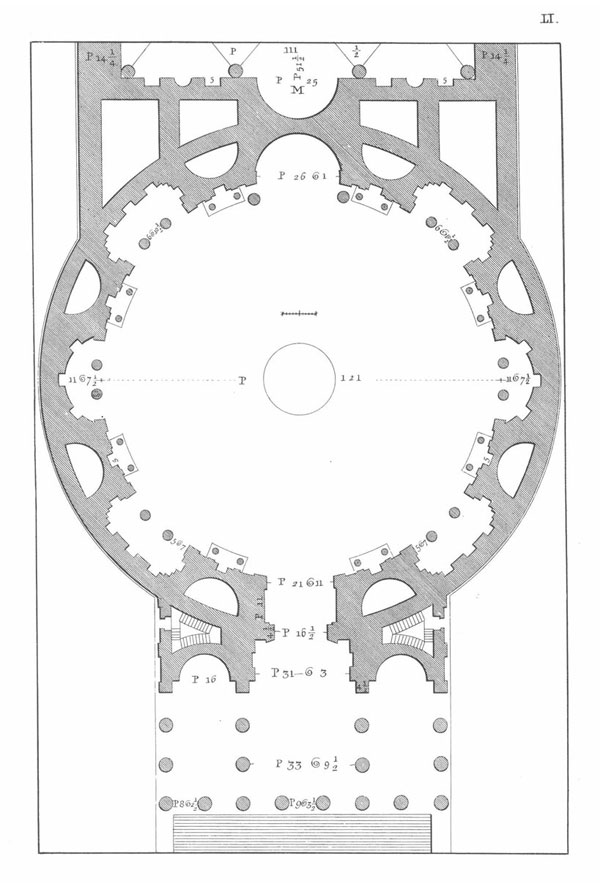

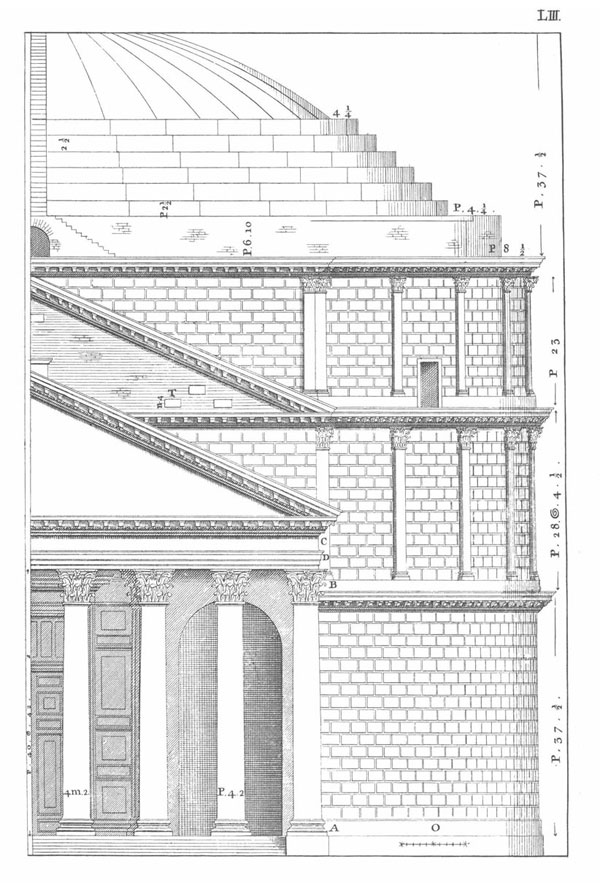

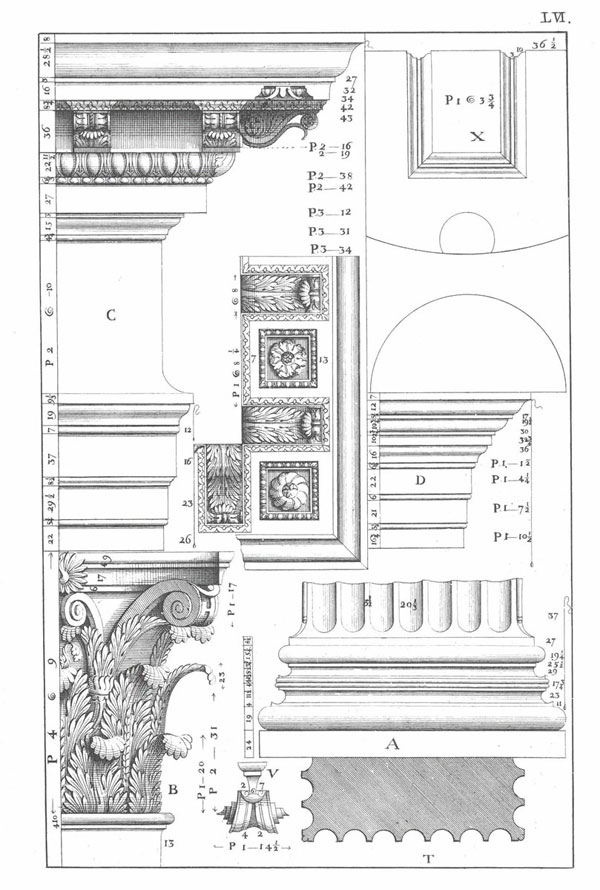

The Rotunda which is the jewel in the crown of Jefferson’s design is based on Palladio’s drawings of the Pantheon in Rome (Book Four plate LI to LX). Excellent though this building is, it is a far cry from the Pantheon in terms of size, materials and function. But to his audience, who had never been to Rome, this would perhaps resemble the real thing. This building has suffered a fire and much restoration and so it is hard to know what is original. On the portico that faces the road, the column bases have the unusual single astragal between two scotias profile, it made me think that perhaps Jefferson was looking at Vignola’s treatise as well as Palladio’s, but I then discovered that this was a later addition by McKimm, Mead and White, which makes perfect sense. The Jefferson portico on the lawn side has the conventional double astragal, in imitation of the Pantheon - as I’d expect.

There is extensive use of painted formed sheet metal (perhaps zinc) in imitation of stone or wood for window surrounds and the entablature to the porticos. It works surprisingly well although I doubt very much that this is a material which Jefferson would use.

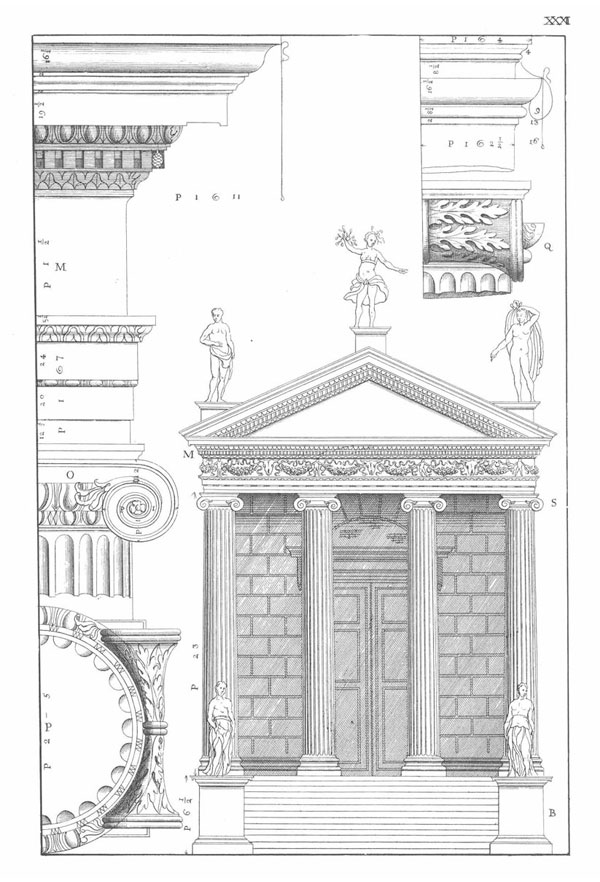

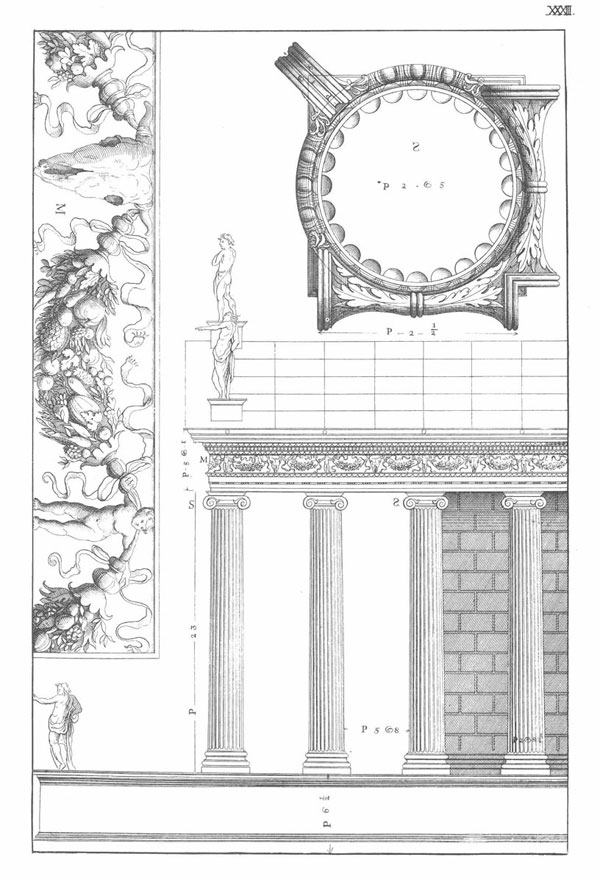

Pavilion II is based on the Roman temple of Fortuna Virilis, as drawn by Palladio on plates XXXI to XXXIII of Book Four. Jefferson has even given it the awkward corner capitals, which Palladio shows in such in such detail. The distinctive swag frieze has also been faithfully reproduced.

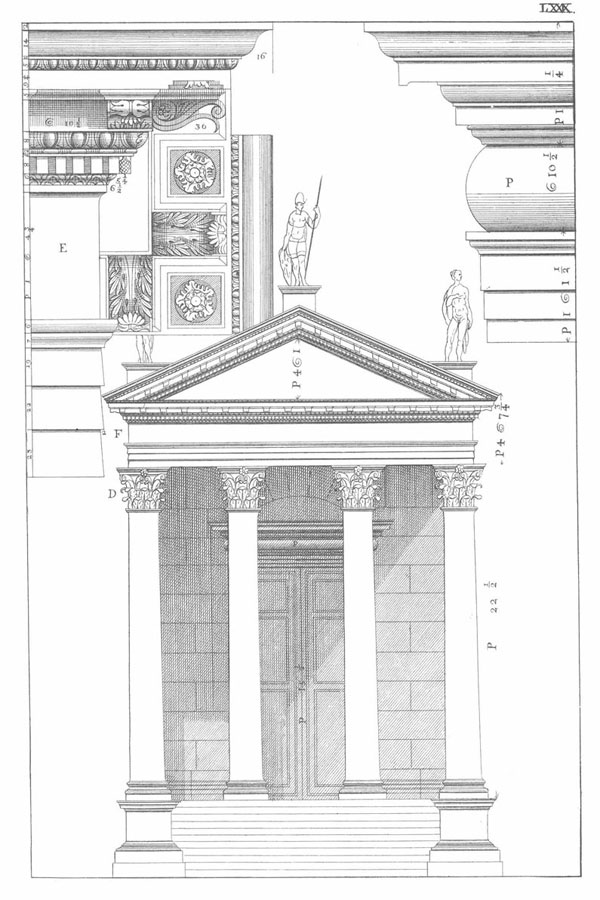

Pavilion III is my favourite, I love the use of Corinthian on an otherwise modest building. What is distinctive about the portico is the tight column spacing, which I would see as a direct reference to Palladio’s Corinthian temple in Pula as shown on plate LXXIX of his Book Four.

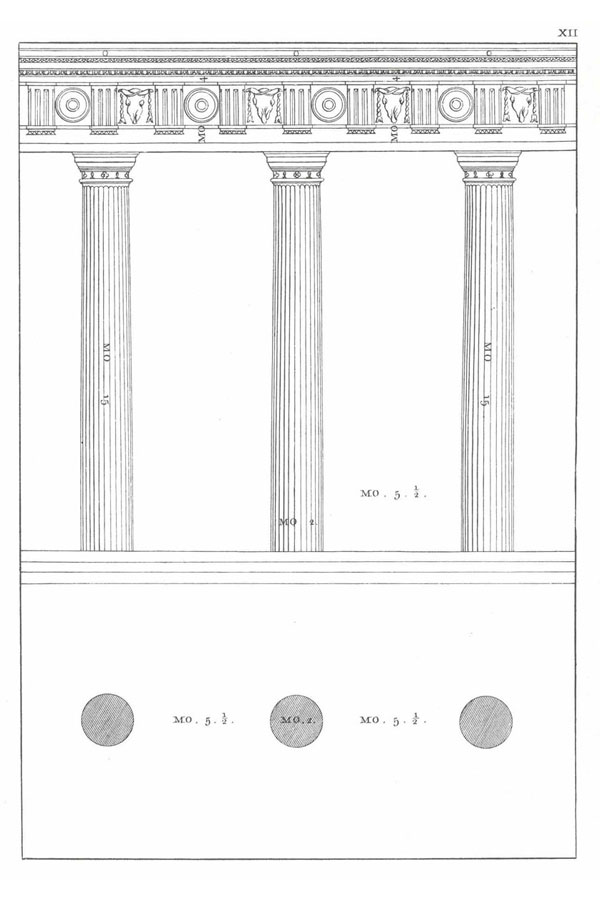

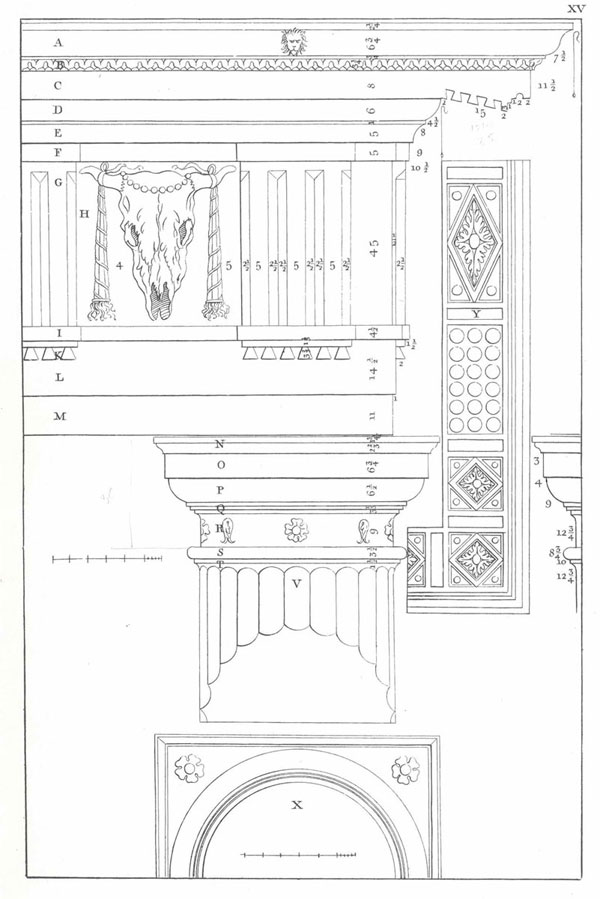

Pavilion X is based on Palladio’s Doric in Book One plates XII to XV. Unusually this Doric has no base, but Palladio does render a baseless Doric on plate XII. It is a quirky looking building with the two sizes of similar columns fighting for attention while the heaviness of the portico has a Hawksmoorian character.

This pavilion has been restored, perhaps controversially, using a stone colour which Jefferson would have originally used for the architectural elements rather than white. The university now has a dilemma whether to go with what Jefferson intended or continue with the white which the alumni know and love from their student days. If I had the choice, I would continue with the stone colour. At this building they have also reinstated the parapet above the pediment which was a feature of some of the other pavilions as well.

The University of Virginia is a testament to the genius of Palladio and the sound judgment of Jefferson. With few resources and simple craftsmanship, the use of Palladio can turn base metal into gold. One of the strengths of classical architecture is that it allows the architects themselves to be of modest ability yet produce the most beautiful work. You do not need to be a genius to be a classical architect and I should know! Just follow a few simple rules with taste and judgment... it’s almost too easy.