Mount Pleasant: Fortress or Circus?

“This is a great example of how big developments should work – working with local communities to design real neighbourhoods that work for the existing community.”

Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London

London, despite slings and arrows, is booming. It has re-discovered its role as a global city at the heart of a mercantile world economy. This was a role partially forgotten for much of the last century and one which it has arguably not played since the twin disasters of World War I and protectionism ended the international capitalism of the nineteenth century. In consequence, after a systemic decline in London’s population of nearly two million between 1939 and the late 1980s, London’s population is now on track to exceed nine million. Cockney or plutocrat, Somali or Scot, newly-arrived or never-left, where will they all live?

One answer would be to expand outwards. Another would be to gently densify in many different places. This is how London has grown in the past. The terraces of Mayfair and Bloomsbury were greenfield developments of four or five storeys almost unthinkable today. And the City of London has grown from two storey medieval thatched huts to forty storey towers on the same street pattern.

However, growing out or densifying evenly have been made very difficult by the green belt (which prevents outward expansion) and by the comparatively risky British planning system (which prevents gentle densification thanks to its uncertainty which acts as a ‘barrier to entry’ to small landowners or builders).

The main route, therefore, that we are taking to providing new homes is by maximising density on a comparatively small number of sites. We build a lot in a few places. Create Streets’ analysis of nineteen large regeneration and redevelopment sites shows that the typical increase in height is around 230 per cent with only one redevelopment having a final maximum height of fewer than 10 storeys. These sites in turn tend to be controlled by major developers – who can afford the high costs and risks of building ‘superdensity.’

But is this what people want? In one poll, only 27 per cent of those polled said they would be ‘happy living in a tall building.’ In contrast 56 percent would not be happy. In another poll, the terraced house and mansion-block flats were, by some distance, felt to be the most suitable ways to meet Londoners’ housing needs. Either something is very wrong with the people or something is very wrong with the way we are running, regulating and incentivising our land and development markets.

Mount Pleasant – the site and the history.

Create Streets’ first project was a site that typifies these tensions. Mount Pleasant is half a mile northwest of the City of London, on the borders of Islington and Camden. It was a unique site of land in central London which had never had streets running through it and which acted as a barrier to movement through the neighbourhood.

Initially open fields running down to the banks of the River Fleet, Mount Pleasant became a dumping ground for rubbish generated by the expanding city in the late seventeenth century, with a mound of refuse building up over the next 100 years, hence the ironic name. In 1794 the rubbish mound was flattened to build Clerkenwell Gaol. The prison closed in 1877 and since the late nineteenth century the site has served as a major Royal Mail sorting office and open-air car park.

In 2012, following on from a joint Camden and Islington Supplementary Planning Document, the Royal Mail made public their plans to develop much of the site. While the principle was widely supported, the proposals themselves proved deeply controversial locally. In the comments left in feedback forms at the 2013 public exhibition there were over eight times as many concerns expressed as there were expressions of support with the proposed scheme. The main concern expressed (on 66 per cent of responses) was the height and density of the proposal. Professionals were not that impressed either. A well-known developer commented, ‘it’s a very bad proposal.’ The journalist Sir Simon Jenkins added; ‘It is a mockery of localism and drains whatever character might have been installed in this potentially charming corner of London… a bland aesthetic of glass towers and rectangles for foreigners to buy-to-leave.”

Four main things seem to have gone wrong:

-

A difficult planning framework which encouraged ‘blocks in space’ not streets and squares. The London and local council planning framework and preferences makes building the type of highly textured street beloved by most Londoners very hard to do. Rules on light and overlooking, a cultural inability on the part of most planners to insist on popular design and the lack of clear design codes all conspire to encourage bland and ‘lumpen’, cheaply-faced, over-sized buildings which feel as if they have been ‘pulled apart’. Rather than building finely-grained streets and squares on new sites we are building ‘blocks in space’ – Duplo not Lego.

-

The wrong starting point. An early decision was made to retain a large proportion of the site for operations and car parking and the remainder delivered in phases. This decision came from a pragmatic view on the future operation of the sorting office without the creative input of a development partner or the community. If a developer, with a focus on financial value, and the local community, with their focus on social value, had been involved in that early decision we believe that a better and more valuable scheme could have been the result.

-

An insufficiently strategic, connected, or London-wide approach to the site. The masterplan was broken into four portions each designed by separate architects. It is fragmented and inward facing. Many locals described it as a ‘fortress’, rather than one that seizes the opportunity to open routes north-south or east-west improving not just local but London-wide connectivity.

-

A failure to successfully engage with the local community and some consequently important disconnects. For example, based on a meeting with the local community, architects and landscape experts working in key roles on the scheme appear to have been unaware of the Christopher Hatton Primary School to the southwest of the site. This may have led to the positioning of a 15-storey tower block opposite the school that caused consternation among teachers, parents and children.

The local community asked Create Streets to work with residents and other local stakeholders to design an alternative. Working over three years we did so. First of all, and on a zero budget, we worked up a high-level alternative master plan. Then, when modest funds become available, we worked up the scheme in more detail and submitted the largest ever community right-to-build order for part of the site.

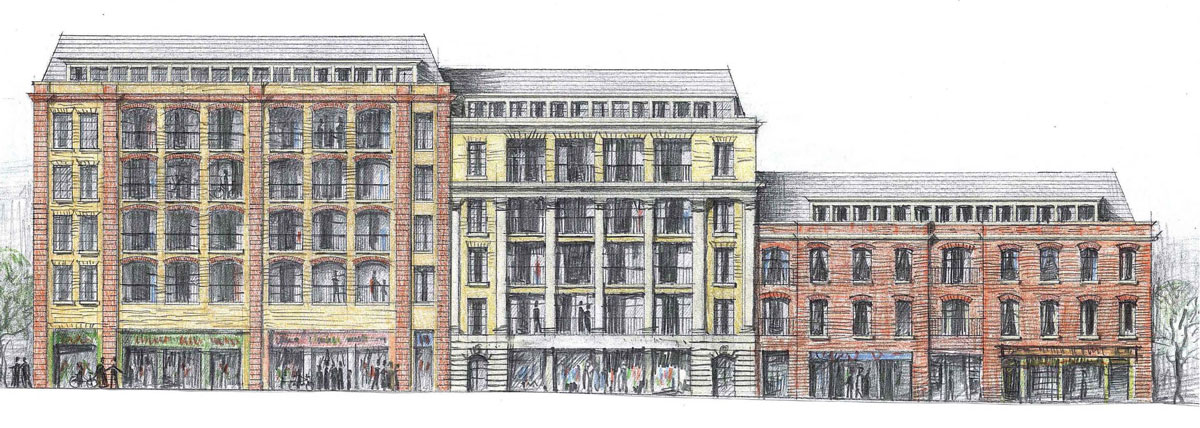

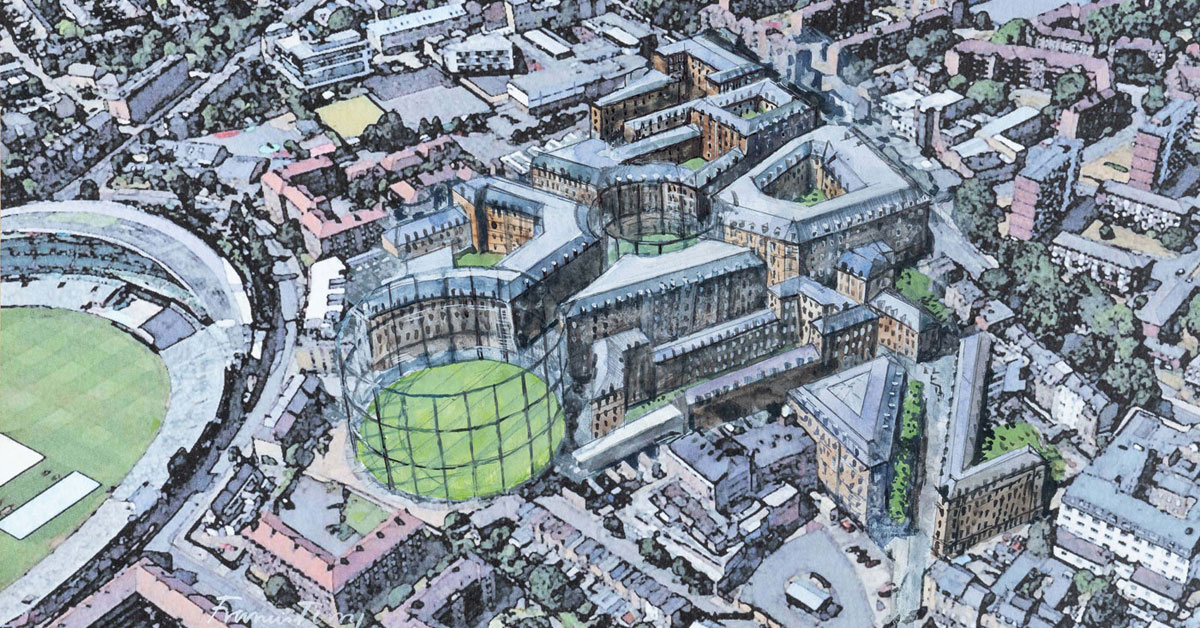

Designing with residents not at them. Our co-design approach involved seven public meetings and workshops; the input of thousands of people locally and across London; and received widespread local and national media attention.

The initial alternative master plans were worked up in early 2014 with a small number of professionals and local residents who were reflecting conversations they had had with many of their neighbours. Two designs were drafted that reflected earlier suggestions from the community and encapsulated the public response to the Royal Mail scheme. These two options were presented and discussed at a public meeting on 7 May 2014. Comments made during the meeting included: “It’s just great”; “It’s inspirational”; “wow”; “the whole of London could fight for Mount Pleasant Circus”; “it’s great”; “I’m delighted to see the curves”; “it’s very British.” The preferred scheme was then shared much more widely. Between 28 June and 13 July 2014, the Mount Pleasant Association (MPA) questioned 258 residents over several days on the proposal and their preference between it and the Royal Mail Group’s (RMG’s) scheme. Support for the community’s scheme was overwhelming – at 99 per cent.

-

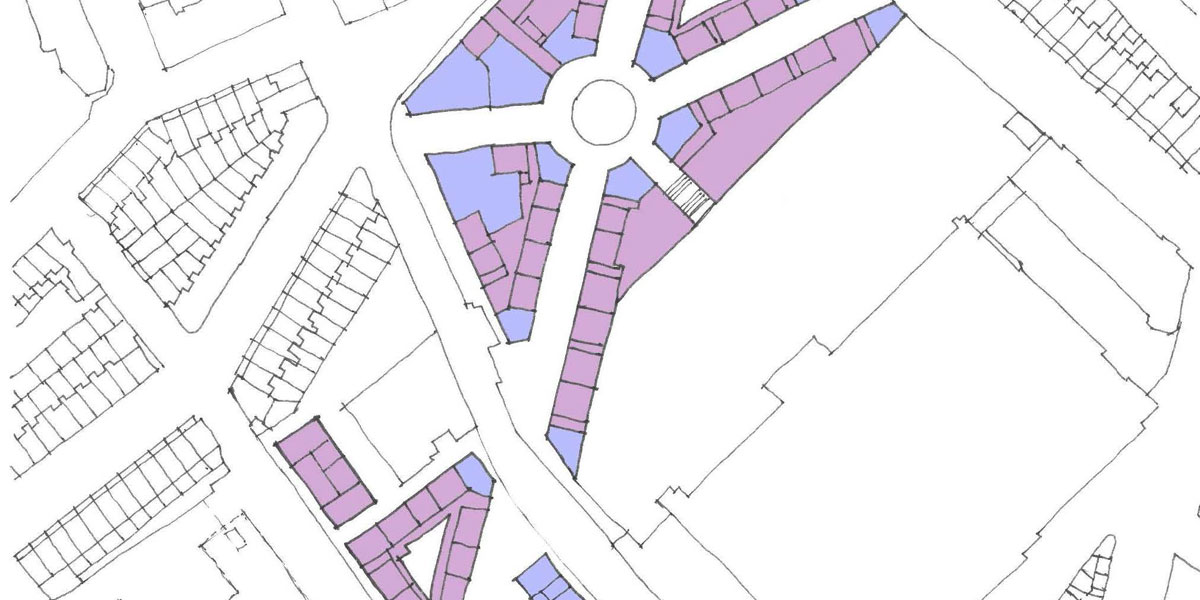

Site Plan of the Mount Pleasant Proposal. Retail/commercial shown in blue and residential shown in mauve.

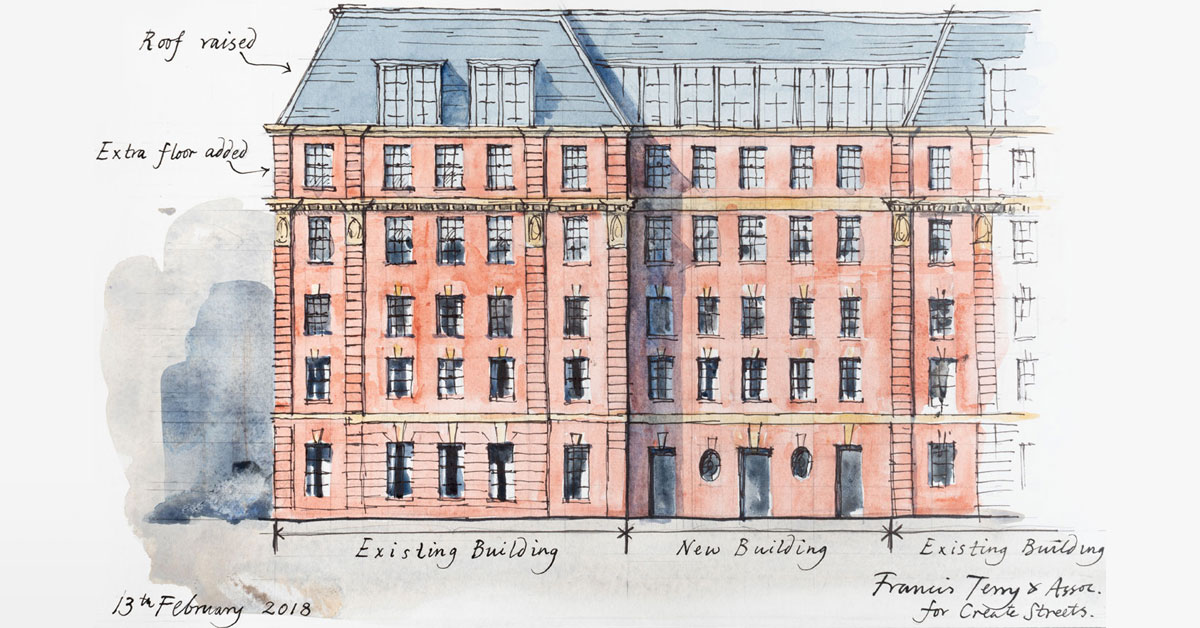

When we managed to win some funding a wider team of architects, engineers, planning consultants and surveyors then worked up this scheme in more detail, resolved technical and topographical complexities, ran further well-attended workshop weekends and presentations and presented a revised scheme for a Community Right to Build Order for the South Eastern portion of the site in 2016.

This more detailed process was able to lead to a scheme that had about 40 more homes than the approved scheme and indeed more development overall whilst fitting in rather better with the surrounding neighbourhood. Sir Simon Jenkins described it as “seriously visionary” and it was praised by consecutive London Mayors. Boris Johnson called it “very beautiful” and Sadiq Khan lauded our approach to community co-design.

Mount Pleasant Circus was the heart of the proposal, giving the new neighbourhood its name and focal point. Responding to intensely strong community feedback, we also proposed a new Mount Pleasant Gardens outside Christopher Hatton Primary School. This featured traffic-calming, landscaping and increasing the size of the existing open space to create a new well-defined triangular pocket park overlooked on all three sides by houses, flats or shops. This was in place of a road and a tower block. The new flats and shops that looked down on Mount Pleasant incorporated the London Plan’s stringent requirement for balconies without ruining the elevation.

We also proposed The Upper Walk. In the Royal Mail proposals the roof of their lorry park was a sequestrated ‘meadow’, inaccessible to the public and visible only to the residents occupying the upper storeys of the surrounding flats. Our proposals instead created a series of open and attractive public spaces, taking advantage of the natural change of height by connecting these spaces by new bridges. Finally, our masterplan proposed strong corners that linked to the surrounding neighbourhood and invited entry into Mount Pleasant. We treated the site’s corners (for example with Calthorpe Street and Farringdon Road) very differently to the approved scheme. Neighbourhood support for this master plan was strong and consistent throughout the design process.

Seven key themes seemed to underpin this clear support.

- A stronger sense of place

“It will help to give a sense of community that this whole stranded area badly needs.”

“It is so refreshing to have this alternative vision for what is a huge site in central London, with intelligent design and a focus on quality housing, rather than the shoddy second-rate package currently on offer from Royal Mail.”

“Stupendous, here is new architecture which reflects the London urban character in the area and gives us some good green space.”

“I want my neighbourhood to contain places that are resonant and useful to our community—rather than dumbed-down non-places dreamed up on computer screens and imposed by developers. I want the history and spirit of my area to be revealed and added to—not obliterated and ignored.”

- A liking for the less ‘fortress-like’ nature of the scheme, especially at the corners

“It…is no longer a fortress. I urge all involved in the future of this site to think of the benefits of these plans and reject the deficits of the RMG’s universally hated plans.”

“A vast improvement on the RMG proposals. The open corners around the outside make the area much more inviting and engaging with the wider community.”

“The radial access of both schemes make the new proposals ‘belong’ to the community.”

- Preferring the positioning of the open space

“Islington needs well-designed green space. Your design provides for that. Good luck!”

“A logical ‘green’ pathway which will encourage residents and visitors to enjoy the environment rather than just trying to get through or past it. It is a viable opportunity to make real improvements to the area.”

- Preferring the lack of high rise

“I fully support the Create Streets alternative scheme.…development that is on a human scale and responds to the traditional London layout of the area with its green squares and terraces.”

“Buildings no more than 6-8 storeys high would be good.”

“The height of the buildings is of great importance and should not exceed eight storeys.”

- A strong liking for Mount Pleasant Circus

“It’s important to support ideas like the Circus which continues that sense of civic dignity and social porosity. It adds to London’s historic mix.”

“I instantly loved the Circus design.”

“The circus is elegant, enriching the whole area and breaking up a continuous run from one end to the other. This is impressive, well done!”

“The Mount Peasant Circus proposal is inspiring. The cross-roads through a round park will intrigue and entertain users. It is playful.”

- A preference for the more traditional façade design

“The new plan is fit for human beings: it works in every practical way and it has charm and dignity.”

“The frontages attest to a more nuanced and far less hostile response to the locale, while keeping to density targets.”

- An appreciation that the proposal has been created with the local community

“Thank you so much for supporting the local community.”

“Profound thanks to all who have given freely of their time and expertise to develop these plans.”

Our work at Mount Pleasant has had an impact on the national discussion about planning, design and how to work with residents not at them. However, despite coming very close to securing an alternative planning permission and the support of a major investor and mixed-use developer, we did not win this battle. In 2017 Royal Mail sold the site to Taylor Wimpey, who are at present building out the rather mundane initial planning permission which was readily able to secure planning consent but is ill equipped to create a neighbourhood of which London can be proud.

Team: Create Streets, Francis Terry and Associates, calfordseaden, Maddox Associates, Urban Engineering Studio (David Taylor), Space Syntax, Alexandra Steed Urban.

(1) A complete and unedited record of comments can be seen at Boys Smith et al, (2015) Mount Pleasant Circus and Fleet Valley Gardens, pp. 54-7.

You might also like...

-

Queen Mother Square, Poundbury, Dorset

-

West Hampstead: What is a Mansion Block?

-

Little Oval: Cricket and Gasworks

-

Northampton: Narrow Fronts, Many Doors

-

Wimbledon: What is It to Be Premier?

-

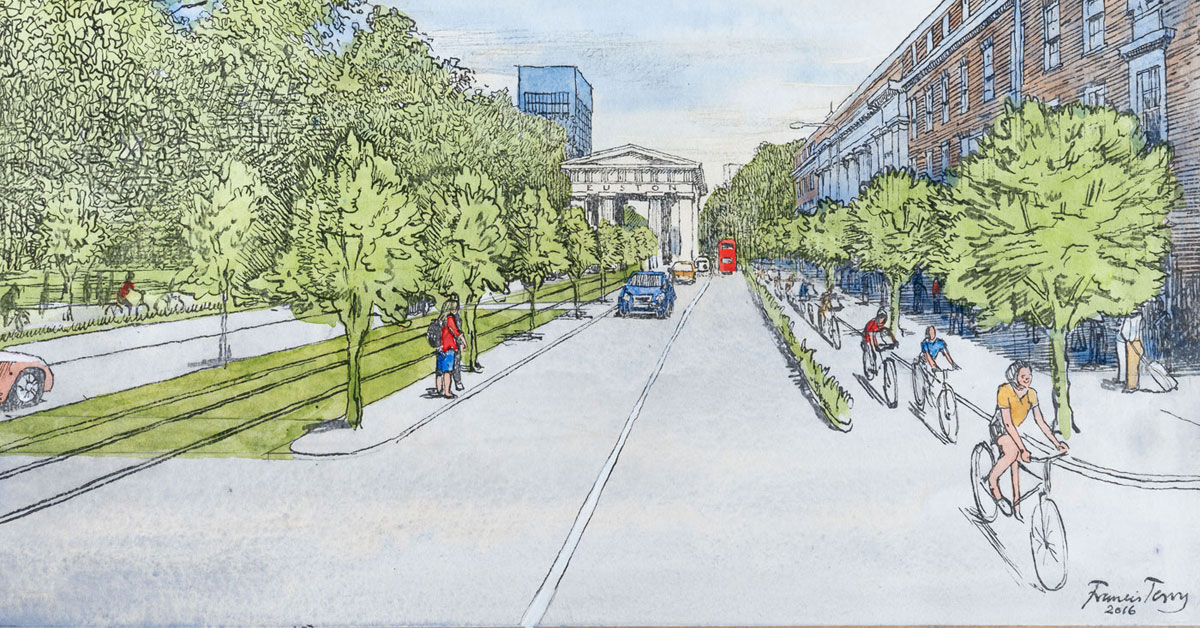

Euston Road: Can an Arch a Boulevard Make?

-

Empress Place: Join the Street, Don't Destroy It

-

The Sutton Estate: Anywhere or Sutton Square?