The Architecture of the 18th Century: From Rococo to NeoClassicism

The 18th century is where I go routinely for inspiration. There is something magical about Georgian architecture which everyone seems to enjoy no matter who they are. Historically I see the 18th century as the transition from traditional society to the modern world. As catholicism gradually lost its power, the Baroque style also began to lose its grip and evolved into the Rococo. Like the last moments of a dying star which produces the many and varied elements of the universe, the Rococo was Baroque in an explosive, dynamic and beautiful decline.

With Rococo came new styles, Chinoiserie influenced by newly discovered decoration from China and Gothick (with a ‘k’) a style which looked back to medieval architecture yet void of the philosophy behind it. Architects and designers of all types enjoyed mixing these three different styles as can be seen most notably in the furniture of Chippendale. This new-found freedom to indulge in any style of choice seemed at odds with the spirit of the age. At this time, the Age of Enlightenment was in full swing, Sir Isaac Newton published his ‘Principia’ in 1687 and architects, perhaps jealous of the scientist’s ability to have ‘principles’ which were inherent and unchanging, searched around for their own principles which would have similar power and weight. With these thoughts in mind, and influenced by the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Marc-Antoine Laugier argued for a more essential approach to architecture. He speculated on how the primitive man would build, unshackled by the dictates of culture and society. He developed an argument that all architectural elements should carry out the role they were originally designed for rather than being merely decorative confection. For example, columns should hold weight, pediments should be gables and neither should be whimsically applied to buildings because they looked ‘pretty’. This was the beginning of modernism, but these new radical ideas were always expressed within a neo-classical vocabulary. It took another two hundred years for architects to abandon Corinthian capitals, triglyphs and all the other elements of the style.

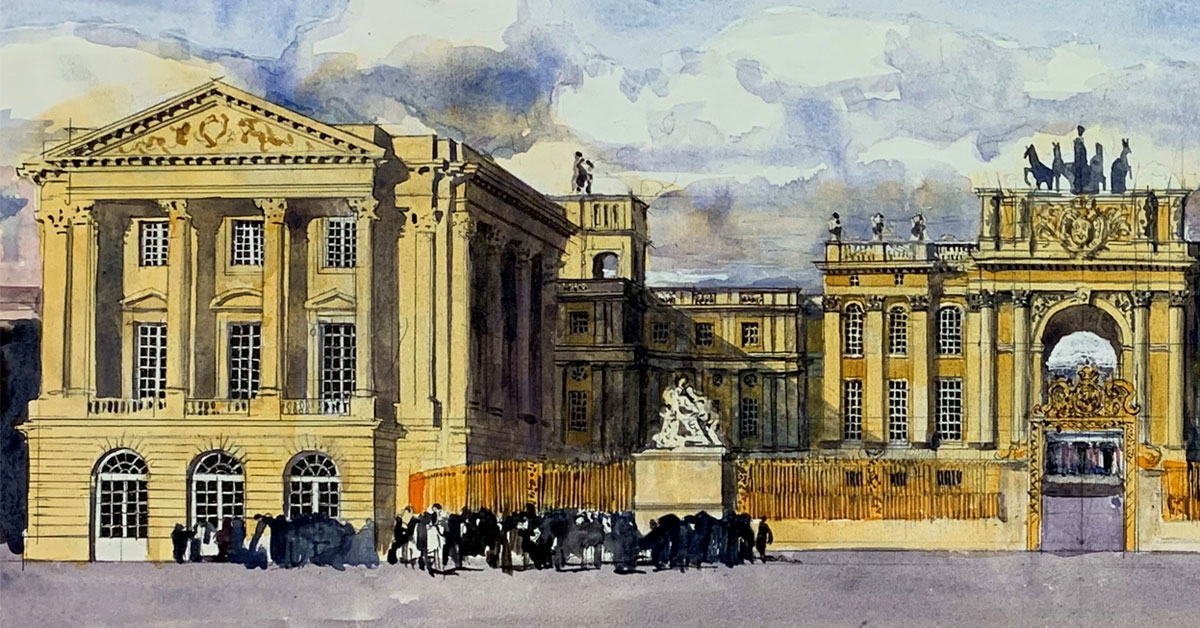

The adoption of Classicism direct from ancient Rome was seen as a way of going back to the essence of the style free from all the mistakes and inconsistencies of the Baroque and Rococo. It was a new style, albeit a revival, appropriate to a new, more enlightened age. Classicism has a way of meaning different things to different people and is often used to bolster the prevailing ideology. In England, it was seen as the rational style of the new Hanoverian monarch as a reaction to the catholic and Baroque of the Stuarts. For the French it was a style suitable for a new republic as they sought to echo ancient Rome, the paragon of all republics. As well as these political influences, at this time the Grand Tour was becoming the way for young aristocrats to show they were men of taste and sophistication.

Towards the end of the century, Greece opened up to these Grand Tourists which led to a fashion for Greek architecture. To some, Greece was seen as ‘true’ classical architecture from which the Romans were seen as a later, crude representation of the original.

Through out the 18th century the Gothic style was always in the background; initially a playfully and frivolous style which gradually evolved and became increasingly established and serious. To a certain extent neo-classicism was eclipsed by gothic during the 19th century, yet it still lived on, right though to the present day.

I hope you enjoy this video, it has been hard for me to condense a period which I love so much into one lecture. I have therefore needed to gloss over many architects and buildings which are important to maintain the melodic line. This is not a dry academic lecture, it is the musings of a practicing neo-classicism architect with a passion for the 18th century.